Questões de Vestibular Sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 5.992 questões

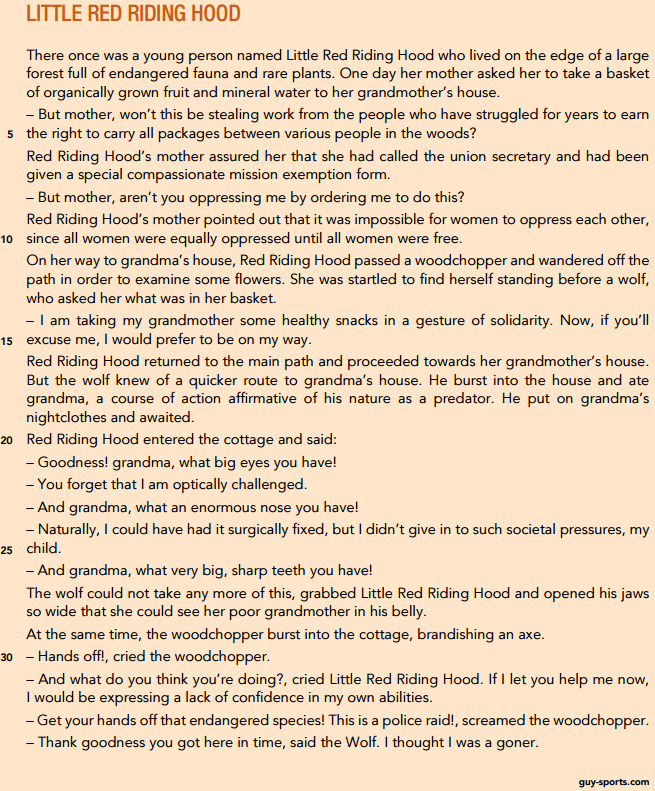

This modern version of the fairy tale Little Red Riding Hood addresses different social issues.

One of these issues is:

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder à questão.

Disparity in life spans of the rich and the poor is growing

Sabrina Tavernise

February 12, 2016

Experts have long known that rich people generally live longer than poor people. But a growing body of data shows a more disturbing pattern: Despite big advances in medicine, technology and education, the longevity gap between high-income and low-income Americans has been widening sharply.

The poor are losing ground not only in income, but also in years of life, the most basic measure of well-being. In the early 1970s, a 60-year-old man in the top half of the earnings ladder could expect to live 1.2 years longer than a man of the same age in the bottom half, according to an analysis by the Social Security Administration. Fast-forward to 2001, and he could expect to live 5.8 years longer than his poorer counterpart.

New research released this month contains even more jarring numbers. Looking at the extreme ends of the income spectrum, economists at the Brookings Institution found that for men born in 1920, there was a six-year difference in life expectancy between the top 10 percent of earners and the bottom 10 percent. For men born in 1950, that difference had more than doubled, to 14 years. For women, the gap grew to 13 years, from 4.7 years. “There has been this huge spreading out,” said Gary Burtless, one of the authors of the study.

The growing chasm is alarming policy makers, and has surfaced in the presidential campaign. During a Democratic debate, Senator Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton expressed concern over shortening life spans for some Americans. “This may be the next frontier of the inequality discussion,” said Peter Orszag, a former Obama administration official now at Citigroup, who was among the first to highlight the pattern. The causes are still being investigated, but public health researchers say that deep declines in smoking among the affluent and educated may partly explain the difference.

Overall, according to the Brookings study, life expectancy for the bottom 10 percent of wage earners improved by just 3 percent for men born in 1950 compared with those born in 1920. For the top 10 percent, though, it jumped by about 28 percent. (The researchers used a common measure – life expectancy at age 50 – and included data from 1984 to 2012.)

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia a charge para responder à questão.

Leia a charge para responder à questão.

Leia a charge para responder à questão.

TEXTO 8

Aos 60 anos, Rossmarc foi confinado na cadeia Raimundo Pessoa em Manaus, dividindo uma cela com 80 detentos. Dormia no chão junto de uma fossa sanitária. Para manter-se vivo usava toda a sua inteligência para fazer acordos com os detentos. Lá havia de tudo: drogados, jagunços, pseudomissionários, contrabandistas etc. Fora vítima do advogado. Com toda a lábia, nunca fora a Brasília defender Rossmarc. Por não ter apresentado a defesa, foi condenado a 13 anos de prisão. O advogado sumira, Rossmarc perdera o prazo para recorrer. Como era estrangeiro, os juízes temiam que fugisse do Brasil. O juiz ordenou sua prisão imediata. A cela, com oitenta detentos, fervilhava, era mais do que o inferno. Depressivo, mantinha-se tartamudo num canto, remoendo sua história, recordando-se dos bons tempos em que navegava pelos rios da Amazônia com seus amigos primatas.

Visitas? Só a de Pássaro Azul. Mudara-se também para Manaus e, sem nada dizer a Rossmarc, para obter dinheiro, prostituía-se num cabaré. Estava mais magra e algumas rugas se mostravam em seu rosto antes reluzente, agora de cor negra desgastada. Com o intuito de obter dinheiro, tanto para Rossmarc pagar as contas de dois viciados em crack no presídio, como para as custas de um advogado inexperiente, pouco se alimentava e ao redor dos olhos manchas entumecidas apareciam, deixando-a como alguém que consumia droga em exagero. As noitadas no cabaré enfumaçado e fedorento deixavam-na enfraquecida. Mas não deixara de amar o biólogo holandês. Quando fugira do quilombola, naquela noite, jurara amor eterno e não estava disposta a quebrar o juramento.

Enquanto Pássaro Azul se prostituía para obter os escassos recursos, Rossmarc, espremido entre os oitenta detentos, procurava desesperadamente uma luz no fim do túnel. Lembrava-se dos amigos influentes, de jornalistas, de políticos, e cada vez que Pássaro Azul o visitava, ele implorava que procurasse essas pessoas. Pássaro Azul corria atrás, mas sequer era recebida. Quem daria ouvidos a uma negra que se dizia íntima de Rossmarc, o biólogo que cometera crimes de biopirataria? Na visita seguinte, Rossmarc indagava:

— E dai, procurou aquela pessoa?

Para não magoar o amado, ela respondia que todos estavam muito interessados em sua causa. Dizia, entretanto, sem entusiasmo, com os olhos acuados e baixos, para não ver o rosto magro e chupado de Rossmarc. Entregava-lhe o pouco dinheiro que economizava, fruto da prostituição, e saia de lá com os olhos rasos d’água, tolhendo os soluços.

Numa noite no cabaré, Pássaro Azul conheceu um homem gordo e vesgo, que usava correntões de ouro. Dizia-se dono de um garimpo no meio da selva. Bebia e fumava muito, ria alto, com gargalhadas por vezes irritantes. Entre todas as raparigas, escolheu Pássaro Azul, que lhe fez todas as vontades, pervertendo-se de forma baixa e vil. Foram três noitadas intermináveis, mas Pássaro Azul aprendera a administrar a bebida. Não era tola, como as demais, que se embebedavam a ponto de caírem e serem arrastadas. Era carinhosa com o fazendeiro e saciava-lhe todos os caprichos. Não o abandonava, sentava em seu colo gordo e fazia-lhe agrados fingidos. Dava-lhe mais bebida e um composto de viagra, e o rosto gordo se avermelhava como de um leão enraivecido. Então, ela o puxava para o quarto sórdido. Na cama, enfrentava como guerreira o monte de carne e ossos, trepando sobre suas grandes papadas balofas e cavalgando, como uma guerreira. O homem resfolegava, gritava, gemia, uivava, mas Pássaro Azul não parava aquela louca cavalgada.

[...]

(GONÇALVES, David. Sangue verde. Joinville:

Sucesso Pocket, 2014. p. 217-218.)

In Text 8, Gonçalves refers to different professions, such as, lawyer, judge, biologist and journalist. Read the following definitions and match the most appropriate word from the sequence given below:

1. lawyer 2. biologist 3. journalist 4. judge

5. defence lawyer 6. prosecution lawyer

I- Someone who tries to prove in court that someone is not guilty.

II- Someone who tries to prove in court that someone is guilty.

III-The official in control of a court who decides how criminals should be punished.

IV- Someone whose job is to advise people about laws, write formal agreements, or represent people in court.

V- Someone who studies or works in biology.

VI- Someone who writes news reports for newspapers, magazines.

Choose the best sequence:

TEXTO 7

A gota que fez transbordar a caixa da paciência de vovó foi um casalzinho folgado. Cansada da algazarra, do som da sanfona, que por três dias e três noites vinha balançando os alicerces da Casa, vovó foi procurar refúgio na paz de seu quarto. Que paz que nada, ali também a festa rolava solta. Abismada, ela viu um casalzinho iniciando sua lua de mel, imaginem onde? Na cama de vovó! Pena que o urinol estivesse vazio. Furiosa, Ana Vitória pensou em apelar para o chicote. Depois seu pensamento voltou para os primeiros dias de seu casamento, lembrou-se da urgência que a fazia deixar tudo por fazer e ir atrás do marido no roçado. Viu a si mesma, viu os dois, ela e o marido, um casal corado e feliz se deitando debaixo de qualquer árvore. Dez meses após o casamento nasceu o primeiro filho, seguido de outros, um por ano. A leveza daquele início parecia tão distante, tão irreal. Uma lagrimazinha de saudade marejou seus olhos abatidos, rolou pela face cansada e foi morrer no peito murcho. Desanimada, ela pensou que nunca mais ia parar de ter filhos, de lavar bundinhas melecadas de cocô. Acabou deixando os pombinhos em paz, eles que aproveitassem a vida enquanto era possível. Mas avisou aos interessados que preferia perder um bom quinhão de suas terras a continuar convivendo com tamanha barafunda. Assim, a ideia remota da criação de um arraial foi posta em prática. Doações foram feitas e o terreno demarcado.

As construções começaram a nascer com a rapidez dos cogumelos. Primeiro a igreja com a torre central, beiral duplo em madeira recortada em bicos. Paredes azuis, janelas brancas. Feinha a pobre igreja, mas nem por isso desprezada. Talvez sua maior virtude estivesse na singeleza, no aconchego. A igrejinha era o orgulho do povoado. Sobre o altar feito por um carpinteiro caprichoso, a imagem de um Cristo cansado, a cabeça pensa, o olhar vazio. Descascado, ensanguentado, provocava nos fieis uma piedade quase dolorosa. Foi nessa igreja que meus pais me apresentaram ao Nosso Criador.

(BARROS, Adelice da Silveira. Mesa dos inocentes. Goiânia: Kelps, 2010. p. 74-75.)

TEXTO 6

Rápido, rápido

Sofro – sofri – de progéria, uma doença na qual o organismo corre doidamente para a velhice e a morte. Doidamente talvez não seja a palavra, mas não me ocorre outra e não tenho tempo de procurar no dicionário – nós, os da progéria, somos pessoas de um desmesurado senso de urgência. Estabelecer prioridades é, para nós, um processo tão vital como respirar. Para nós, dez minutos equivalem a um ano. Façam a conta, vocês que têm tempo, vocês que pensam que têm tempo. Enquanto isso, eu vou escrevendo aqui – e só espero poder terminar. Cada letra minha equivale a páginas inteiras de vocês. Façam a conta, vocês. Enquanto isso, e resumindo:

8h15min – Estou nascendo. Sou o primeiro filho – que azar! – e o parto é longo, difícil. Respiro, e já vou dizendo as primeiras palavras (coisas muito simples, naturalmente: mamã, papá) para grande surpresa de todos! Maior surpresa eles têm quando me colocam no berço – desço meia hora depois, rindo e pedindo comida! Rindo! Àquela hora,

8h45min – eu ainda podia rir.

9h20min – Já fui amamentado, já passei da fase oral – meus pais (ele, dono de um pequeno armazém; ela, de prendas domésticas) já aceitaram, ao menos em parte, a realidade, depois que o pediatra (está aí uma especialidade que não me serve) lhes explicou o diagnóstico e o prognóstico. E já estou com dentes! Em poucos minutos (de acordo com o relógio de meu pai, bem entendido) tenho sarampo, varicela, essas coisas todas.

Meus pais me matriculam na escola, não se dando conta que às 10h40min, quando a sineta bater para o recreio, já terei idade para concluir o primeiro grau. Vou para a escola de patinete; já na esquina, porém, abandono o brinquedo que parece-me então muito infantil. Volto-me, e lá estão os meus pais chorando, pobre gente.

10h20min – Não posso esperar o recreio; peço licença à professora e saio. Vou ao banheiro; a seiva da vida circula impaciente em minhas veias. Manipulo-me. Meu desejo tem nome: Mara, da oitava série. Por enquanto é mais velha do que eu. Lá pelas onze horas poderia namorá-la – mas então, já não estarei no colégio. Ali, me foge o doce pássaro da juventude.

[...]

(SCLIAR, Moacyr. Melhores contos. 6. ed. São Paulo: Global, 2003. p. 54-55.)

In Text 6, the character has a disease called progeria. The abstract that follows is a research about Hutchinson– Gilford progeria syndrome. Choose the best sequence of words to complete the text:

Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) is an extremely rare 1 ____________ that causes premature, rapid aging shortly 2 ____________ birth. Recently, de novo point mutations in the Lmna 3 ____________ have been found in individuals with HGPS. Lmna encodes lamin A and C, the A-type lamins, which are an important 4 ____________ of the nuclear envelope. The most common HGPS 5 ____________ is located at codon 608 (G608G). This mutation creates a cryptic splice site within exon 11, 6 ____________ deletes a proteolytic cleavage site within the expressed mutant lamin A. Incomplete processing of prelamin A results in nuclear lamina abnormalities that can be observed in 7 ____________ studies of HGPS cells. [...]

(Pollex, RL; Hegele, RA. Hutchinson–Gilford progeria

syndrome. Clinical Genetics, Denmark, v. 66, n. 5, p. 375-

381, nov. 2004. Available on: http://www.ingentaconnect.

com/search/article?option1=tka&value1=PROGERIA&pa

geSize=10&index=1. Accessed on: July 14th, 2015.)

TEXTO 5

Raios de sol ao meio

Mais uma vez ele aparecia na minha frente como se tivesse vindo do nada. Seus olhos eram grandes e negros e pareciam ter nascido bem antes dele. Suas espinhas se agigantavam conforme o ângulo de que eram vistas. Sua orelha era algo indescritível. Além de orelha ela era disforme, meio redonda e meio achatada nas pontas. Ela era meio várias coisas. Uma orelha monstro. A boca era alguma coisa que só estava ali para cumprir seu espaço no rosto. Era boca porque estava exatamente no lugar da boca. E era a segunda vez que ele me mobilizava. Mas no conjunto de elementos díspares reinava uma sensualidade ímpar que me tirava de mim sem que eu soubesse navegar no outro que em mim surgia. De mim não sabia entender o que emanava para ele em toda a sua estranha vastidão de patologia visual. No meio sol da meia-noite as coisas se anunciaram e antes que a madrugada avançasse a lua em sua metade escondida ardeu com um olhar malicioso e sorriu.

(GONÇALVES, Aguinaldo. Das estampas. São Paulo: Nankin, 2013. p. 177.)

TEXTO 4

Aprígio – Saia, Dália! (Dália abandona o quarto, correndo, em desespero. Sogro e genro, face a face) Vim aqui para.

Arandir (para o sogro quase chorando) – Está satisfeito?

Aprígio – Vim aqui.

Arandir (na sua cólera) – Está satisfeito? O senhor é um dos responsáveis. Eu acho que é o senhor. O senhor que está por trás...

Aprígio – Quem sabe?

Arandir – Por trás desse repórter. O senhor teve a coragem de. Ou pensa que eu não sei? Selminha me contou. Contou tudo! O senhor fez insinuações. Insinuações! A meu respeito!

Aprígio – Você quer me.

Arandir (sem ouvi-lo) – O senhor fez tudo! Tudo pra me separar de Selminha!

Aprígio – Posso falar?

Arandir (erguendo a voz) – O senhor não queria o nosso casamento!

Aprígio (violento) – Escuta! Vim aqui saber! Escuta! Você conhecia esse rapaz?

Arandir (desesperado) – Nunca vi.

Aprígio – Era um desconhecido?

Arandir – Juro! Por tudo que há de mais! Que nunca, nunca!

Aprígio – Mentira!

Arandir (desesperado) – Vi pela primeira vez!

Aprígio – Cínico! (muda de tom, com uma Ferocidade) Escuta! Você conhecia o rapaz. Conhecia! Eram amantes! E você matou. Empurrou o rapaz!

Arandir (violento) – Deus sabe!

Aprígio – Eu não acredito em você. Ninguém acredita. Os jornais, as rádios! Não há uma pessoa, uma única, em toda a cidade. Ninguém!

Arandir (com a voz estrangulada) – Ninguém acredita, mas eu! Eu acredito, acredito em mim!

Aprígio – Você, olha!

Arandir – Selminha há de acreditar!

Aprígio (fora de si) – Cala a boca! (muda de tom) Eu te perdoaria tudo! Eu perdoaria o casamento. Escuta! Ainda agora, eu estava na porta ouvindo. Ouvi tudo. Você tentando seduzir a minha filha menor!

Arandir – Nunca!

Aprígio – Mas eu perdoaria, ainda. Eu perdoaria que você fosse espiar o banho da cunhada. Você quis ver a cunhada nua.

Arandir – Mentira!

Aprígio – Eu perdoaria tudo. (mais violento) Só não perdoo o beijo no asfalto. Só não perdoo o beijo que você deu na boca de um homem!

Arandir (para si mesmo) – Selminha!

Aprígio (muda de tom, suplicante) – Pela última vez, diz! Eu preciso saber! Quero a verdade! A verdade! Vocês eram amantes? (sem esperar a resposta, furioso) Mas não responda. Eu não acredito. Nunca, nunca, eu acreditarei. (numa espécie de uivo) Ninguém acredita!

Arandir – Vou buscar minha mulher. (Aprígio recua, puxando o revólver.)

Aprígio (apontando) – Não se mexa! Fique onde está!

Arandir (atônito) – O senhor vai.

Aprígio – Você era o único homem que não podia casar com a minha filha! O único!

Arandir (atônito e quase sem voz) – O senhor me odeia porque. Deseja a própria filha. É paixão. Carne. Tem ciúmes de Selminha.

Aprígio (num berro) – De você! (estrangulando a voz) Não de minha filha. Ciúmes de você. Tenho! Sempre. Desde o teu namoro, que eu não digo o teu nome. Jurei a mim mesmo que só diria teu nome a teu cadáver. Quero que você morra sabendo. O meu ódio é amor. Por que beijaste um homem na boca? Mas eu direi o teu nome. Direi teu nome a teu cadáver. (Aprígio atira, a primeira vez. Arandir cai de joelhos. Na queda, puxa uma folha de jornal, que estava aberta na cama. Torcendo-se. abre o jornal, como uma espécie de escudo ou bandeira. Aprígio atira, novamente, varando o papel impresso. Num espasmo de dor, Arandir rasga a folha. E tomba, enrolando-se no jornal. Assim morre.) Aprígio – Arandir! (mais forte) Arandir! (um último canto) Arandir!

(RODRIGUES, Nelson. O beijo no asfalto. Rio

de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1995. p. 101-104.)

TEXTO 2

VI

Para entenderes bem o que é a morte e a vida, basta contar-te como morreu minha avó.

— Como foi?

— Senta-te.

Rubião obedeceu, dando ao rosto o maior interesse possível, enquanto Quincas Borba continuava a andar.

— Foi no Rio de Janeiro, começou ele, defronte da Capela Imperial, que era então Real, em dia de grande festa; minha avó saiu, atravessou o adro, para ir ter à cadeirinha, que a esperava no Largo do Paço. Gente como formiga. O povo queria ver entrar as grandes senhoras nas suas ricas traquitanas. No momento em que minha avó saía do adro para ir à cadeirinha, um pouco distante, aconteceu espantar-se uma das bestas de uma sege; a besta disparou, a outra imitou-a, confusão, tumulto, minha avó caiu, e tanto as mulas como a sege passaram-lhe por cima. Foi levada em braços para uma botica da Rua Direita, veio um sangrador, mas era tarde; tinha a cabeça rachada, uma perna e o ombro partidos, era toda sangue; expirou minutos depois.

— Foi realmente uma desgraça, disse Rubião.

— Não.

— Não?

— Ouve o resto. Aqui está como se tinha passado o caso. O dono da sege estava no adro, e tinha fome, muita fome, porque era tarde, e almoçara cedo e pouco. Dali pôde fazer sinal ao cocheiro; este fustigou as mulas para ir buscar o patrão. A sege no meio do caminho achou um obstáculo e derribou-o; esse obstáculo era minha avó. O primeiro ato dessa série de atos foi um movimento de conservação: Humanitas tinha fome. Se em vez de minha avó, fosse um rato ou um cão, é certo que minha avó não morreria, mas o fato era o mesmo; Humanitas precisa comer. Se em vez de um rato ou de um cão, fosse um poeta, Byron ou Gonçalves Dias diferia o caso no sentido de dar matéria a muitos necrológios; mas o fundo subsistia. O universo ainda não parou por lhe faltarem alguns poemas mortos em flor na cabeça de um varão ilustre ou obscuro; mas Humanitas (e isto importa, antes de tudo) Humanitas precisa comer.

Rubião escutava, com a alma nos olhos, sinceramente desejoso de entender; mas não dava pela necessidade a que o amigo atribuía a morte da avó. Seguramente o dono da sege, por muito tarde que chegasse à casa, não morria de fome, ao passo que a boa senhora morreu de verdade, e para sempre. Explicou-lhe, como pôde, essas dúvidas, e acabou perguntando-lhe:

— E que Humanitas é esse?

— Humanitas é o princípio. Mas não, não digo nada, tu não és capaz de entender isto, meu caro Rubião; falemos de outra coisa.

— Diga sempre.

Quincas Borba, que não deixara de andar, parou alguns instantes.

— Queres ser meu discípulo?

— Quero.

— Bem, irás entendendo aos poucos a minha filosofia; no dia em que a houveres penetrado inteiramente, ah! nesse dia terás o maior prazer da vida, porque não há vinho que embriague como a verdade. Crê-me, o Humanitismo é o remate das coisas; e eu, que o formulei, sou o maior homem do mundo. Olha, vês como o meu bom Quincas Borba está olhando para mim? Não é ele, é Humanitas...

— Mas que Humanitas é esse?

— Humanitas é o principio. Há nas coisas todas certa substância recôndita e idêntica, um princípio único, universal, eterno, comum, indivisível e indestrutível, — ou, para usar a linguagem do grande Camões:

Uma verdade que nas coisas anda,

Que mora no visíbil e invisíbil.

Pois essa sustância ou verdade, esse princípio indestrutível é que é Humanitas. Assim lhe chamo, porque resume o universo, e o universo é o homem. Vais entendendo?

— Pouco; mas, ainda assim, como é que a morte de sua avó...

— Não há morte. O encontro de duas expansões, ou a expansão de duas formas, pode determinar a supressão de uma delas; mas, rigorosamente, não há morte, há vida, porque a supressão de uma é a condição da sobrevivência da outra, e a destruição não atinge o princípio universal e comum. Daí o carácter conservador e benéfico da guerra. Supõe tu um campo de batatas e duas tribos famintas. As batatas apenas chegam para alimentar uma das tribos, que assim adquire forças para transpor a montanha e ir à outra vertente, onde há batatas em abundância; mas, se as duas tribos dividirem em paz as batatas do campo, não chegam a nutrir-se suficientemente e morrem de inanição. A paz, nesse caso, é a destruição; a guerra é a conservação. Uma das tribos extermina a outra e recolhe os despojos. Daí a alegria da vitória, os hinos, aclamações, recompensas públicas e todos os demais efeitos das ações bélicas. Se a guerra não fosse isso, tais demonstrações não chegariam a dar-se, pelo motivo real de que o homem só comemora e ama o que lhe é aprazível ou vantajoso, e pelo motivo racional de que nenhuma pessoa canoniza uma ação que virtualmente a destrói. Ao vencido, ódio ou compaixão; ao vencedor, as batatas.

— Mas a opinião do exterminado?

— Não há exterminado. Desaparece o fenômeno; a substância é a mesma. Nunca viste ferver água? Hás de lembrar-te que as bolhas fazem-se e desfazem-se de contínuo, e tudo fica na mesma água. Os indivíduos são essas bolhas transitórias.

— Bem; a opinião da bolha...

— Bolha não tem opinião. Aparentemente, há nada mais contristador que uma dessas terríveis pestes que devastam um ponto do globo? E, todavia, esse suposto mal é um benefício, não só porque elimina os organismos fracos, incapazes de resistência, como porque dá lugar à observação, à descoberta da droga curativa. A higiene é filha de podridões seculares; devemo-la a milhões de corrompidos e infectos. Nada se perde, tudo é ganho. Repito, as bolhas ficam na água. Vês este livro? É Dom Quixote. Se eu destruir o meu exemplar, não elimino a obra, que continua eterna nos exemplares subsistentes e nas edições posteriores. Eterna e bela, belamente eterna, como este mundo divino e supradivino.

(ASSIS, Machado de. Quincas Borba. 18. ed. São

Paulo: Ática, 2011. p. 26-28.)

INSTRUCTION: Consider texts 1 and 2 to solve the question.

After reading text 1 and text 2, one can state that

INSTRUCTION: Answer question according to text 2.

INSTRUCTION: Answer question according to text 2.

INSTRUCTION: Read the statements below about text 2 to solve the question.

1. The author decided to be an archeologist.

2. The author changed her professional goals.

3. The author used to travel to Mexico with her family.

4. The author took part in an excavation in the USA.

The facts presented by the author about her life are chronologically organized according to the sequence