Questões Militares de Inglês - Interpretação de texto | Reading comprehension

Foram encontradas 2.202 questões

1. It stands for both up-to-date and conventional patterns. 2. People wear it in different ways. 3. Both men and women can wear it. 4. People cannot avoid an arrogant attitude when they put it on.

Mark the affirmative(s) that is/are present in the text.

Read the text and answer the question.

Read the statements.

I- Anxiety symptoms are often easy to identify.

II- Avoiding situations that induce anxiety can make fears increase.

III- Excessive and frequent preoccupation are signs of anxiety disorder.

IV- Someone socially anxious is not afraid to be negatively judged by people.

The correct information, according to the text, can be found in sentences

Read the text and answer the question.

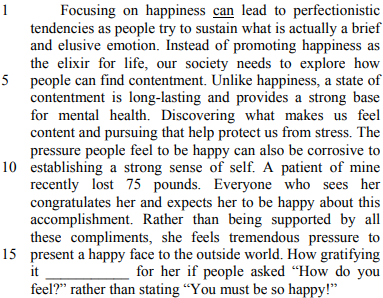

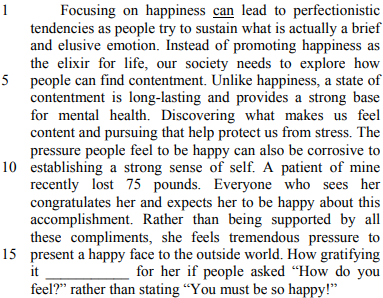

The pursuit of happiness can end in pain

Maggie Mulqueen, psychologist

Adapted from https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/suicide-studentathletes-happiness-contentment-rcna27992

Read the text and answer the question.

The pursuit of happiness can end in pain

Maggie Mulqueen, psychologist

Adapted from https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/suicide-studentathletes-happiness-contentment-rcna27992

II. Texto de interpretação para resolução de questões de INGLÊS

February 25, 2019

By LiseAlves, Senior Contributing Reporter RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL - Exactly one month after Brazil's most deadly mining disasters, firefighters and volunteers still search for at least 131 people still missing under tons of mud left behind after adam in the Feijão mining complex, owned by Brazilian giant, Vale, gave way on January 25th. So far 179 corpses have been retrieved and identified.

"The search starts at 5 am, when the teams get up. At 6:30 am, we gather for directions, a safety briefing and guidelines of what will be dane throughout lhe day. The teams are then taken into the field," firefighter Lt. Col. Anderson Passos tells journalists.

"At the end of lhe day, when the teams return, they give us feedback on how lhe search went. We then hold a meeting to plan lhe next day and everything repeats itself," concluded the official.

(Adapted from: https://riollmesonline.com/brazil-news/río-po!ítics/month-after-brumadínho-dam-tragedy-131-still-míssing/)

One of the most important sources of force on a ship is her own propeller and the pilot must understand the action of a propeller in order to be able to predict its action on ship.

A propeller produces side forces in addition to thrust along the propeller shaft. A ship can rotates to starboard or port as function of these side forces.

Pilot Antonio is studying propeller side force, on a single right-hand screw propeller, and knows that it can be broken down in four parts: following wake effect, inclination effect, helical discharge effect and shallow submergence effect. Antonio wrote the following consideration:

I) The following wake effect produces a net force tending to move the stern to right and cause the ship to veer to the port.

II) The inclination effect is net effect that tends to twist the ship to the right.

III) The shallow submergence effect tends the stern to starboard and cause the ship to veer to the left.

IV) The helical discharge effect tends to turn the ship to the right.

From the list of Antonio is correct to affirm, according to the book “Naval Shiphandling”, that:

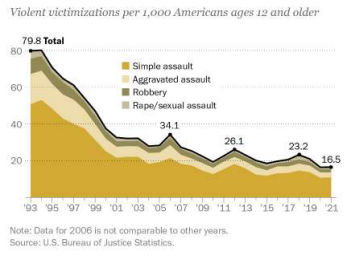

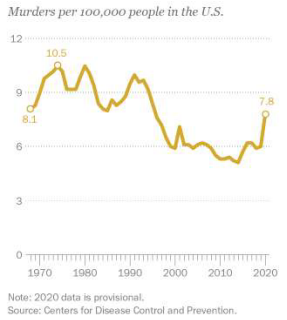

There are many reasons why voters might be concerned about violent crime, ______ official statistics do not show an increase in the nation’s total violent crime rate.

Both the FBI and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a roughly 30% increase in the U.S. murder rate between 2019 and 2020, marking one of the largest year-over-year increases ever recorded.

What the word roughly means in the sentence?