Questões de Concurso

Sobre interpretação de texto | reading comprehension em inglês

Foram encontradas 10.134 questões

Instructions: answer the question based on the following text.

Source: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/ikigai-hygge-lagom-swedish-danish-japaneses-candinavian-lifestyle-happiness-meaning-of-life-a7956141.html

“Depression, an extreme feeling of sadness and hopelessness, can be the result of continued and increasing stress.”

“Stress can make people angry, moody, or nervous”

“When people are under stress, they often overreact to little problems.”

“It can cause stomachaches and problems digesting food.”

"Stop the world, I want to get off!”

1. It can make people feel nervous 2. It can cause panic attacks 3. It can make people feel elated 4. It can make people fell angry

1. Bliss 2. Depression 3. Alcoholism 4. Whimsy

Which of the following characteristics is concerned with an effective teaching?

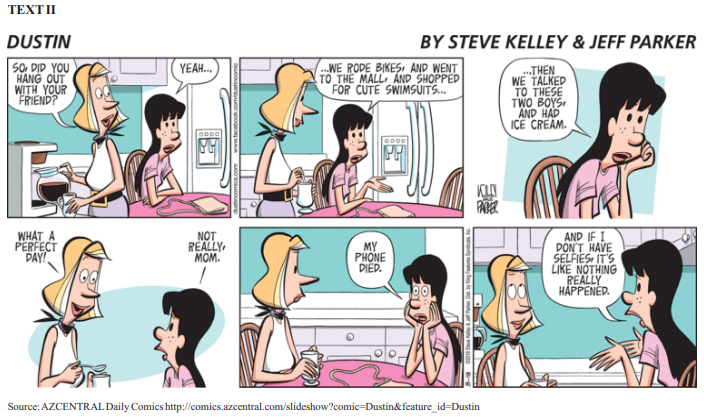

According to the comics, it is CORRECTto say that:

TEXT III

I. Please give me _____ more ice cream. II. I don't have ______ ice cream. III. She will be very angry if you don't bring ______. IV. I have _____ very delicious ice cream for you.

Mark the CORRECT arswer.

I. ________ time do we have to be at school? At eight o'clock. II. ________ bus goes to the centre, number 20 or 21? III. ________ do you feed your dog? Milk.

Mark the CORRECT arswer.

He asked us, "Are they waiting outside?"