Questões de Concurso

Sobre interpretação de texto | reading comprehension em inglês

Foram encontradas 10.014 questões

“Falisha and I had a horrible fight last night, but this morning we made it up with each other.”

We can say that

Read and answer.

“Petro made fun of Jonathan’s clothing style.”

We can assume that

Mark the alternative that completes the blank.

“Janice found a shirt ______ at her room.”

Read the text below and answer the following question based on it.

Disponível em:<https://baneofyourresistance.com/2012/09/14/break-the-urgency-induced-block/>. Acessado em 15 de outubro de 2017.

Read the text below and answer the following question based on it.

Is gene editing ethical?

Gene editing holds the key to preventing or treating debilitating genetic diseases, giving hope to millions of people around the world. Yet the same technology could unlock the path to designing our future children, enhancing their genome by selecting desirable traits such as height, eye color, and intelligence.

While this concept is not new, a real breakthrough came 5 years ago when several scientists saw the potential of a system called CRISPR/Cas9 to edit the human genome.

CRISPR/Cas9 allows us to target specific locations in the genome with much more precision than previous techniques. This process allows a faulty gene to be replaced with a non-faulty copy, making this technology attractive to those looking to cure genetic diseases.

The technology is not foolproof, however. Scientists have been modifying genes for decades, but there are always trade-offs. We have yet to develop a technique that works 100 percent and doesn't lead to unwanted and uncontrollable mutations in other locations in the genome.

In a laboratory experiment, these so-called off-target effects are not the end of the world. But when it comes to gene editing in humans, this is a major stumbling block.

The fact that gene editing is possible in human embryos has opened a Pandora's box of ethical issues.

Here, the ethical debate around gene editing really gets off the ground.

When gene editing is used in embryos — or earlier, on the sperm or egg of carriers of genetic mutations — it is called germline gene editing. The big issue here is that it affects both the individual receiving the treatment and their future children.

This is a potential game-changer as it implies that we may be able to change the genetic makeup of entire generations on a permanent basis.

Read the text below and answer the following question based on it.

Is gene editing ethical?

Gene editing holds the key to preventing or treating debilitating genetic diseases, giving hope to millions of people around the world. Yet the same technology could unlock the path to designing our future children, enhancing their genome by selecting desirable traits such as height, eye color, and intelligence.

While this concept is not new, a real breakthrough came 5 years ago when several scientists saw the potential of a system called CRISPR/Cas9 to edit the human genome.

CRISPR/Cas9 allows us to target specific locations in the genome with much more precision than previous techniques. This process allows a faulty gene to be replaced with a non-faulty copy, making this technology attractive to those looking to cure genetic diseases.

The technology is not foolproof, however. Scientists have been modifying genes for decades, but there are always trade-offs. We have yet to develop a technique that works 100 percent and doesn't lead to unwanted and uncontrollable mutations in other locations in the genome.

In a laboratory experiment, these so-called off-target effects are not the end of the world. But when it comes to gene editing in humans, this is a major stumbling block.

The fact that gene editing is possible in human embryos has opened a Pandora's box of ethical issues.

Here, the ethical debate around gene editing really gets off the ground.

When gene editing is used in embryos — or earlier, on the sperm or egg of carriers of genetic mutations — it is called germline gene editing. The big issue here is that it affects both the individual receiving the treatment and their future children.

This is a potential game-changer as it implies that we may be able to change the genetic makeup of entire generations on a permanent basis.

Read the text below and answer the following question based on it.

Is gene editing ethical?

Gene editing holds the key to preventing or treating debilitating genetic diseases, giving hope to millions of people around the world. Yet the same technology could unlock the path to designing our future children, enhancing their genome by selecting desirable traits such as height, eye color, and intelligence.

While this concept is not new, a real breakthrough came 5 years ago when several scientists saw the potential of a system called CRISPR/Cas9 to edit the human genome.

CRISPR/Cas9 allows us to target specific locations in the genome with much more precision than previous techniques. This process allows a faulty gene to be replaced with a non-faulty copy, making this technology attractive to those looking to cure genetic diseases.

The technology is not foolproof, however. Scientists have been modifying genes for decades, but there are always trade-offs. We have yet to develop a technique that works 100 percent and doesn't lead to unwanted and uncontrollable mutations in other locations in the genome.

In a laboratory experiment, these so-called off-target effects are not the end of the world. But when it comes to gene editing in humans, this is a major stumbling block.

The fact that gene editing is possible in human embryos has opened a Pandora's box of ethical issues.

Here, the ethical debate around gene editing really gets off the ground.

When gene editing is used in embryos — or earlier, on the sperm or egg of carriers of genetic mutations — it is called germline gene editing. The big issue here is that it affects both the individual receiving the treatment and their future children.

This is a potential game-changer as it implies that we may be able to change the genetic makeup of entire generations on a permanent basis.

A team of 30 doctors carried out the surgery - the first of its kind in India - at a state-run hospital.

The boys were born with shared blood vessels and brain tissues, a very rare condition that occurs once in about three million births.

The director of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Randeep Guleria, told the Press Trust of India that the "next 18 days would be extremely critical to ascertain the success of the surgery".

The twins, hailing from a village in eastern Orissa state, were joined at the head - a condition known as craniopagus.

Even before the operation they had defeated the odds; craniopagus occurs in one in three million births, and 50% of those affected die within 24 hours, doctors say.

"Both the children have other health issues as well. While Jaga has heart issues, Kalia has kidney problems," neurosurgeon A K Mahapatra said.

"Though initially Jaga was healthier, now his condition has deteriorated. Kalia is better," he added.

Doctors said the most challenging job after the separation was to "provide a skin cover on both sides of the brain for the children as the surgery had left large holes on their heads".

"If the twins make it, the next step will be reconstructing their skulls," plastic surgeon Maneesh Singhal said.

The first surgery was performed on 28 August when the doctors created a bypass to separate the shared veins that return blood to the heart from the brain.

A team of 30 doctors carried out the surgery - the first of its kind in India - at a state-run hospital.

The boys were born with shared blood vessels and brain tissues, a very rare condition that occurs once in about three million births.

The director of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Randeep Guleria, told the Press Trust of India that the "next 18 days would be extremely critical to ascertain the success of the surgery".

The twins, hailing from a village in eastern Orissa state, were joined at the head - a condition known as craniopagus.

Even before the operation they had defeated the odds; craniopagus occurs in one in three million births, and 50% of those affected die within 24 hours, doctors say.

"Both the children have other health issues as well. While Jaga has heart issues, Kalia has kidney problems," neurosurgeon A K Mahapatra said.

"Though initially Jaga was healthier, now his condition has deteriorated. Kalia is better," he added.

Doctors said the most challenging job after the separation was to "provide a skin cover on both sides of the brain for the children as the surgery had left large holes on their heads".

"If the twins make it, the next step will be reconstructing their skulls," plastic surgeon Maneesh Singhal said.

The first surgery was performed on 28 August when the doctors created a bypass to separate the shared veins that return blood to the heart from the brain.

The underlying mechanisms responsible for phantom limb pain remain unclear. However, it appears that it may arise as a consequence of abnormal neural circuitry in central areas of the brain.

Limited success has been achieved with mirror therapy in which reflections of the unaffected limb can be used to create the illusion that the amputated limb is moving.

Sensors that could detect muscular activity were attached to the stump of the missing arm. The signals received by these sensors were then used to produce an image of an active arm on a computer screen.

Patients were trained to use these signals to control the virtual arm, drive a virtual race car around a track and to copy the movements of an arm on screen with their phantom movements. After twelve 2-hour treatment sessions, the patients underwent follow-up interviews 1, 3 and 6 months later.

Based on the patients' ratings, the intensity, quality, and frequency of pain had reduced by 50% after the treatment.

At the start of the study, 12 patients reported feeling constant pain whereas only 6 did 6months after the treatment. However, one patient thought that there was not a considerable difference in the levels of phantom pain before and after treatment.

The underlying mechanisms responsible for phantom limb pain remain unclear. However, it appears that it may arise as a consequence of abnormal neural circuitry in central areas of the brain.

Limited success has been achieved with mirror therapy in which reflections of the unaffected limb can be used to create the illusion that the amputated limb is moving.

Sensors that could detect muscular activity were attached to the stump of the missing arm. The signals received by these sensors were then used to produce an image of an active arm on a computer screen.

Patients were trained to use these signals to control the virtual arm, drive a virtual race car around a track and to copy the movements of an arm on screen with their phantom movements. After twelve 2-hour treatment sessions, the patients underwent follow-up interviews 1, 3 and 6 months later.

Based on the patients' ratings, the intensity, quality, and frequency of pain had reduced by 50% after the treatment.

At the start of the study, 12 patients reported feeling constant pain whereas only 6 did 6months after the treatment. However, one patient thought that there was not a considerable difference in the levels of phantom pain before and after treatment.

Read the text below and answer the following question based on it.

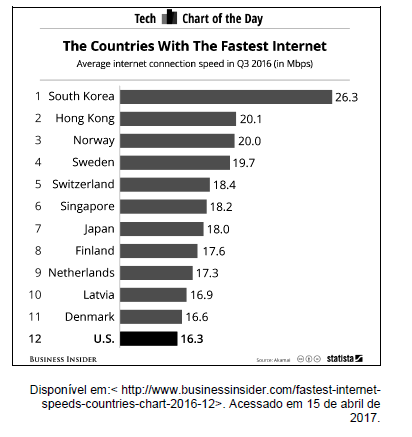

According to the graphic, it is true to assert that

The findings suggest that students’ well-being also

depend on their teachers’

Read the text below and answer the following question based on it.

Natural tooth repair method, using Alzheimer's drug, could revolutionise dental treatments

A new method of stimulating the renewal of living stem cells in tooth pulp using an Alzheimer’s drug has been discovered by a team of researchers at King’s College London.

Following trauma or an infection, the inner, soft pulp of a tooth can become exposed and infected. In order to protect the tooth from infection, a thin band of dentine is naturally produced and this seals the tooth pulp, but it is insufficient to effectively repair large cavities. Currently dentists use manmade cements or fillings, such as calcium and silicon-based products, to treat these larger cavities and fill holes in teeth. This cement remains in the tooth and fails to disintegrate, meaning that the normal mineral level of the tooth is never completely restored.

However, in a paper published today in Scientific Reports, scientists from the Dental Institute at King’s College London have proven a way to stimulate the stem cells contained in the pulp of the tooth and generate new dentine in large cavities, potentially reducing the need for fillings or cements.

The novel biological approach could see teeth use their natural ability to repair large cavities rather than using cements or fillings.

Significantly, one of the small molecules used by the team to stimulate the renewal of the stem cells included Tideglusib, which has previously been used in clinical trials to treat neurological disorders including Alzheimer’s disease.

Using biodegradable collagen sponges to deliver the treatment, the team applied low doses of small molecule glycogen synthase kinase (GSK-3) inhibitors to the tooth. They found that the sponge degraded over time and that new dentine replaced it, leading to complete, natural repair. Collagen sponges are commercially-available and clinicallyapproved, again adding to the potential of the treatment’s swift pick-up and use in dental clinics.

Disponível em:

Read the text below and answer the following question based on it.

Natural tooth repair method, using Alzheimer's drug, could revolutionise dental treatments

A new method of stimulating the renewal of living stem cells in tooth pulp using an Alzheimer’s drug has been discovered by a team of researchers at King’s College London.

Following trauma or an infection, the inner, soft pulp of a tooth can become exposed and infected. In order to protect the tooth from infection, a thin band of dentine is naturally produced and this seals the tooth pulp, but it is insufficient to effectively repair large cavities. Currently dentists use manmade cements or fillings, such as calcium and silicon-based products, to treat these larger cavities and fill holes in teeth. This cement remains in the tooth and fails to disintegrate, meaning that the normal mineral level of the tooth is never completely restored.

However, in a paper published today in Scientific Reports, scientists from the Dental Institute at King’s College London have proven a way to stimulate the stem cells contained in the pulp of the tooth and generate new dentine in large cavities, potentially reducing the need for fillings or cements.

The novel biological approach could see teeth use their natural ability to repair large cavities rather than using cements or fillings.

Significantly, one of the small molecules used by the team to stimulate the renewal of the stem cells included Tideglusib, which has previously been used in clinical trials to treat neurological disorders including Alzheimer’s disease.

Using biodegradable collagen sponges to deliver the treatment, the team applied low doses of small molecule glycogen synthase kinase (GSK-3) inhibitors to the tooth. They found that the sponge degraded over time and that new dentine replaced it, leading to complete, natural repair. Collagen sponges are commercially-available and clinicallyapproved, again adding to the potential of the treatment’s swift pick-up and use in dental clinics.

Disponível em:

Read the text below and answer the following question based on it.

Natural tooth repair method, using Alzheimer's drug, could revolutionise dental treatments

A new method of stimulating the renewal of living stem cells in tooth pulp using an Alzheimer’s drug has been discovered by a team of researchers at King’s College London.

Following trauma or an infection, the inner, soft pulp of a tooth can become exposed and infected. In order to protect the tooth from infection, a thin band of dentine is naturally produced and this seals the tooth pulp, but it is insufficient to effectively repair large cavities. Currently dentists use manmade cements or fillings, such as calcium and silicon-based products, to treat these larger cavities and fill holes in teeth. This cement remains in the tooth and fails to disintegrate, meaning that the normal mineral level of the tooth is never completely restored.

However, in a paper published today in Scientific Reports, scientists from the Dental Institute at King’s College London have proven a way to stimulate the stem cells contained in the pulp of the tooth and generate new dentine in large cavities, potentially reducing the need for fillings or cements.

The novel biological approach could see teeth use their natural ability to repair large cavities rather than using cements or fillings.

Significantly, one of the small molecules used by the team to stimulate the renewal of the stem cells included Tideglusib, which has previously been used in clinical trials to treat neurological disorders including Alzheimer’s disease.

Using biodegradable collagen sponges to deliver the treatment, the team applied low doses of small molecule glycogen synthase kinase (GSK-3) inhibitors to the tooth. They found that the sponge degraded over time and that new dentine replaced it, leading to complete, natural repair. Collagen sponges are commercially-available and clinicallyapproved, again adding to the potential of the treatment’s swift pick-up and use in dental clinics.

Disponível em:

The correct alternatives are:

Outcry as Chinese school makes iPads compulsory

Apple products are incredibly popular in China, but not everyone can afford them

A school in northern China has been criticised for enforcing iPad learning as part of its new curriculum, it's reported.

According to China Economic Daily, the Danfeng High School in Shaanxi province recently issued a notice saying that, “as part of a teaching requirement, students are required to bring their own iPad” when they start the new school year in September.

Staff told the paper that using an iPad would “improve classroom efficiency”, and that the school would managean internet firewall, so that parents would not have to worry about students using the device for other means.

However, China Economic Daily says that after criticism from parents, who felt that it would be an “unnecessary financial burden”, eadmaster Yao Hushan said that having an iPad was no longer a mandatory requirement. Mr Yao added that children who don't have a device could still enrol, but that he recommended students bring an iPad as part of a “process of promoting the digital classroom”.

The incident led to lively discussion on the Sina Weibo social media platform. “Those parents that can't afford one will have to sell a kidney!” one user quipped.

Others expressed concerns about the health implications of long-term electronic device use. “I worry about their vision,” one user said, and another said they would all become “short-sighted and have to wear glasses.”

But others felt that it was a good move in line with new modern ways of teaching. “They are affordable for the average family, one said, “they don't necessarily need to buy the latest model.”

Reporting by Kerry Allen

Taken from: www.bbc.com/news/blogs-news-from-elsewhere

The word STAFF in “Staff told the paper that using an iPAD would improve classroom efficiency” refers in this context to: