Questões de Concurso

Sobre sinônimos | synonyms em inglês

Foram encontradas 1.298 questões

Judge the following item concerning text 7A2.

In “play no part in their culture?”, the word “part” could be

replaced by role or act without any change in the meaning of

the sentence.

Considering information from text 7A1, judge the following item.

In “He noted that sarcasm and irony only make sense within

this widened context”, the adjective “widened” is

synonymous with expanded.

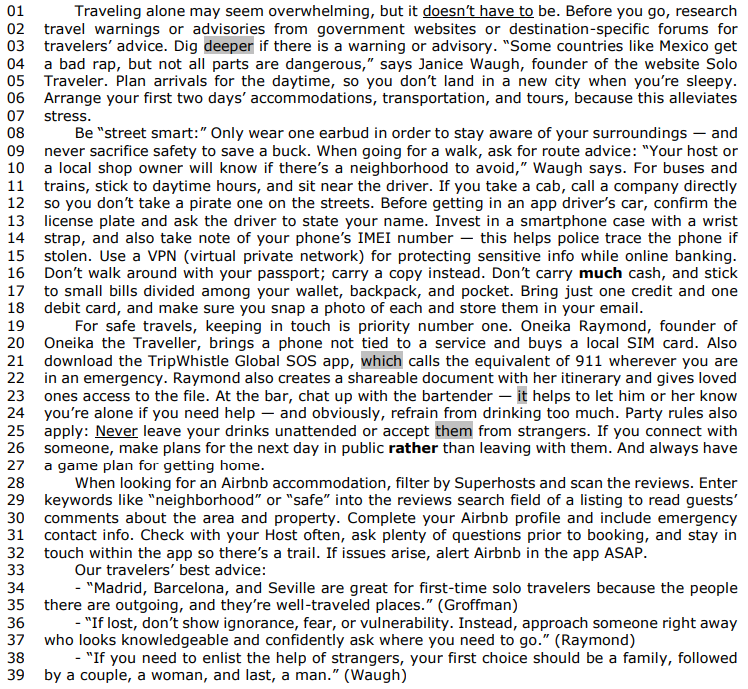

Try these expert tips for a safer solo trip

(Available at: https://news.airbnb.com/try-these-expert-tips-for-a-safer-solo-trip/ – text especially adapted for

this text).

Try these expert tips for a safer solo trip

(Available at: https://news.airbnb.com/try-these-expert-tips-for-a-safer-solo-trip/ – text especially adapted for

this text).

The phrase “to suit the needs” (3rd paragraph) means that the needs will be

From: https://www.glasbergen.com/teen-cartoons/

Text II

Text II

Text 2 – Computers

(Text adapted from History of Computing. Retrieved from

https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~mitra/csFall2006/cs 303/lectures/history.html)

When you hear the term computers, it’s difficult to

imagine different devices from a laptop or a small

desktop. Believe it or not, they weren’t always like

they are today. They used to be very large and

heavy, sometimes as big as an entire room. Some

technology professors historically define computers,

as “a device that can help with computations”. The

word computation involves counting, calculating,

adding, subtracting, etc. The modern definition of a

computer is a little wider, because in our day and

age, computers store, compile, analyze and

compute an enormous amount of information.

Ancient computers were very interesting. Actually,

the first computer may have been located in Great

Britain, at Stonehenge. It is a man-made circle of

large stones. Citizens used it to measure the

weather and forecast the change of seasons. Some

specialists say that another ancient computer is the

abacus. It was used by the early Romans, Greeks,

and Egyptians to count and calculate. Even though

they are no longer in use, certainly, these early

devices are fascinating. Computers are embedded

in our history and some people say that we are

completely dependent of them. No matter the

complexity of the task, easy or difficult, some people

can’t do anything without them. Do you contest or

share this opinion?