Questões de Concurso

Sobre sinônimos | synonyms em inglês

Foram encontradas 1.378 questões

Back in October 2011, Stanford professors launched three free online courses, open to the public. One by one, these courses went massive, with enrollments topping 100.000 students each. Soon the media was calling these courses MOOCs, short for massive open online courses.

Since then, more than 1.200 universities around the world have launched free online courses. In addition to the larger global MOOC platforms, many national governments around the world have launched their own country-specific MOOC platforms, including India, Italy, Israel, Mexico and Thailand.

After a decade of popularization, in 2021, over 220 million students had signed up for at least one course on one of these platforms, and 40 million did so in 2021 alone. MOOCs and MOOC platforms are still growing, even after the crazy “Year of the MOOC” prompted by the pandemic and travel restrictions.

At Class Central, we try to catalog as many MOOCs as possible, and our listing currently includes more than 150.000 of them, from MOOC platforms and other online learning platforms. But due to limited resources, we cannot index every single one. If you’re looking for MOOCs from around the world, this list is our best attempt to catalog all different MOOC platforms that are out there.

Internet: <https://classcentral.com> (adapted).

Keeping in mind the ideas expressed above and the linguistic aspects of the text, judge the following items.

The phrase “short for massive open online courses” (in the last sentence of the first paragraph) can be correctly replaced with which stands for massive open online courses.

Back in October 2011, Stanford professors launched three free online courses, open to the public. One by one, these courses went massive, with enrollments topping 100.000 students each. Soon the media was calling these courses MOOCs, short for massive open online courses.

Since then, more than 1.200 universities around the world have launched free online courses. In addition to the larger global MOOC platforms, many national governments around the world have launched their own country-specific MOOC platforms, including India, Italy, Israel, Mexico and Thailand.

After a decade of popularization, in 2021, over 220 million students had signed up for at least one course on one of these platforms, and 40 million did so in 2021 alone. MOOCs and MOOC platforms are still growing, even after the crazy “Year of the MOOC” prompted by the pandemic and travel restrictions.

At Class Central, we try to catalog as many MOOCs as possible, and our listing currently includes more than 150.000 of them, from MOOC platforms and other online learning platforms. But due to limited resources, we cannot index every single one. If you’re looking for MOOCs from around the world, this list is our best attempt to catalog all different MOOC platforms that are out there.

Internet: <https://classcentral.com> (adapted).

Keeping in mind the ideas expressed above and the linguistic aspects of the text, judge the following items.

The verb “prompted” (in the second sentence of the third paragraph) conveys the same idea as restrained.

The item preserving the same message/idea as the one emphasized in the text below is:

Rahul: Hi, Raj. You 've participated the drawing competition.

Raj: Sure, you know drawing is my bailiwick.

Rahul: What is the topic you chose?

Raj: “Environmental Issues”

Rahul: How many days did it take you to complete it?

Raj: It took me 2.

Rahul: Have the results already? To whom did the prize go?

Raj: A dude in Texas, at least my personal experience has grown...

(Available in: https://brainly.in/question/6727599.)

Read Text | and answer questions 05 to 13.

Netflix is trying to prove to the world that it's all grown up

Netflix is trying to persuade Wall Street that it is now all grown up. After squeezing out millions of additional subscribers via its password sharing crackdown and through the introduction of cheaper advertiser-supported plans, the streamer knows that its growth spurts are coming to an end — and now it wants investors to stop obsessing over those pesky membership numbers and instead focus on other metrics.

"In our early days, when we had little revenue or profit, membership growth was a strong indicator of our future potential. But now we're generating very substantial profit and free cash flow. We are also developing new revenue streams like advertising and our extra member feature, so memberships are just one component of our growth", Netflix told shareholders as it reported quarterly earnings.

To that end, Netflix said that it will no longer report quarterly subscriber numbers, starting in 2025. Alas, the metric that Wall Street has forever judged Netflix on — the metric that prompted legacy media companies to burn endless piles of cash in their bids to compete with the streamer — will be retired. The decision to shut off transparency on the metric represents a significant turning point in the streaming revolution. For years, Netflix has prided itself on being extraordinarily transparent. Now it is aiming to hold its cards closer to its chest. And given that streaming giant is the trendsetter in the space, one could expect that other media companies will be inspired by the company's move and also opt to cease reporting such data.

To be fair, what Netflix is saying isn't necessarily off base either. As the company shifts its business model away from subscriptions and toward advertising and other revenue streams, it makes sense to consider how much time users are spending on the service. The more content a user consumes on Netflix, the more likely they are to continue paying for the service, and the more money Netflix then makes from that single subscriber. "We're focused on revenue and operating margin as our primary financial metrics — and engagement (i.e. time spent) as our best proxy for customer satisfaction,” Netflix underscored in its letter to shareholders.

Regardless, less transparency in an already opaque industry is not ideal. The walled garden of streaming already lacks the same detailed viewership data that Nielsen collects on linear television broadcasters. Now, visibility into the streaming world will get even dimmer.

The announcement from Netflix managed to overshadow its otherwise stellar quarter. The company handily beat expectations and added a staggering 9.3 million subscribers, meaning it now boasts nearly 270 million in total. Netflix also beat analyst expectations on both earnings and revenue. However, it wasn't all good news. Netflix forecasted its subscriber growth to be lower in quarter two, chalking it up to “typical seasonality.” That led the stock to slide nearly 5% in after-hours trading.

Whether "typical seasonality” is solely to blame, or whether the streamer is simply starting to hit a ceiling, is hard to tell. Perhaps it is a mix of both. Whatever the cause, the stock sliding on the less-than-ideal outlook is a prime example of why Netflix wants Wall Street to stop focusing on its subscriber numbers. And, in one year's time, investors won't have a choice.

Adapted from: https://edition.cnn.com/2024/04/19/media/netflix-subscription-numbers/index.html

In "(..) what Netflix is saying isn't necessarily off base either”, "off base” can be replaced, without changing its meaning in the context of the text, by:

Text for the items from 31 to 35.

1 A language is not considered international just

because a great number of people speak it. An enormous

number of people speak Chinese, but Chinese is not the

4 most important language in the world. The main reason

for a language to become international is power – the

political and economic power of the people who speak it.

7 Britain was the world’s leading industrial and

trading country in the 19th century. It colonized many

other countries where English is now spoken. The North

10 America economy is growing fast, making the USA one of

the most important and powerful countries in the world.

These are the reasons why English is a global language.

13 Like anybody else, you need a global language

for communication, not only today, but for your future

as well.

Internet: <www.ahoradecolorir.com.br> (adapted).

Based on the ideas of the text, judge the items from 36 to 40.

It would change the meaning of the last paragraph if the word “anybody” was replaced by nobody in the last period of the text.

Answer question according to TEXT 3 below.

TEXT 3

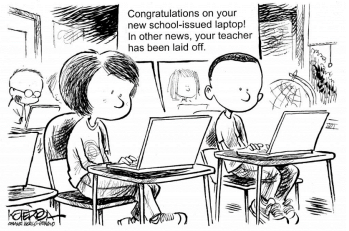

Available at: https://larrycuban.wordpress.com/2019/11/25/evenmore-cartoons-on-technology/. Access on: Apr. 9th, 2024.

Check the comic to answer question.

Fonte: https://media.baamboozle.com/uploads/images/76546/1598950862_26075

Text 2

Available

in:<https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/voices-of-change-ashley-lashley>

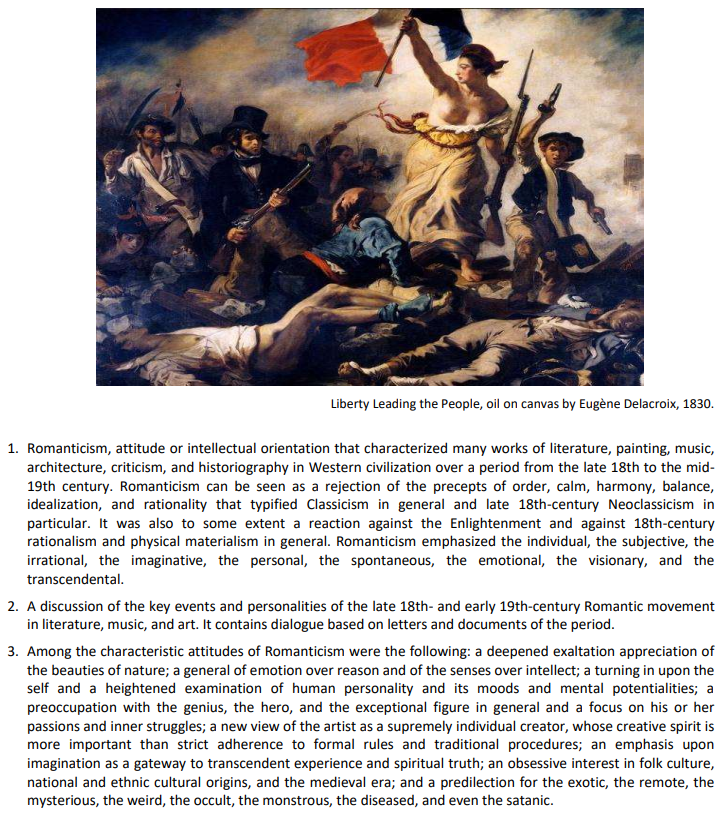

Text 1

Romanticism

BRITANNICA, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Romanticism”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 26 Dec. 2023,

https://www.britannica.com/art/Romanticism. Accessed 1 February 2024

Poor Things – Emma Stone transfixes in Lanthimos’s thrilling carnival of oddness

(Available at: www.theguardian.com/film/2024/jan/14/poor-things-review-yorgos-lanthimos-emma-stonefrankenstein – text specially adapted for this test).

(Available at: education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/earth-day/– text specially adapted for this test).

Read Text I to answer the question.

TEXT I

“One very active research tradition in the field of second language acquisition (SLA) attempts to establish causal relationships between environmental factors and learning. These include the type and quantity of input, instruction and feedback, and the interactional context of learning (Larsen-Freeman and Long 1991). A second very influential line of research and theory in SLA that came to fruition during the 1980s investigates the possible role of universal grammar (UG) in SLA (Eubank 1991b, White 1989). In the Chomskyan tradition, UG refers not to properties of language as the external object of learning but to innate properties of mind that direct the course of primary language acquisition. One question asked within this tradition has been whether or not second language this tradition learners still “have access” to UG, but it is assumed that UG principles are not accessible to learner awareness for any kind of conscious analysis of input. It is possible that SLA is the result of UG (a deep internal factor) acting upon input (an external factor), as proposed by White (1989), but what seems to be left out of such an account is the role of the learner's conscious mental processes.” […]

Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/annual-review-of-applied-linguistics/ (adapted)

Read Text I to answer the question.

TEXT I

“One very active research tradition in the field of second language acquisition (SLA) attempts to establish causal relationships between environmental factors and learning. These include the type and quantity of input, instruction and feedback, and the interactional context of learning (Larsen-Freeman and Long 1991). A second very influential line of research and theory in SLA that came to fruition during the 1980s investigates the possible role of universal grammar (UG) in SLA (Eubank 1991b, White 1989). In the Chomskyan tradition, UG refers not to properties of language as the external object of learning but to innate properties of mind that direct the course of primary language acquisition. One question asked within this tradition has been whether or not second language this tradition learners still “have access” to UG, but it is assumed that UG principles are not accessible to learner awareness for any kind of conscious analysis of input. It is possible that SLA is the result of UG (a deep internal factor) acting upon input (an external factor), as proposed by White (1989), but what seems to be left out of such an account is the role of the learner's conscious mental processes.” […]

Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/annual-review-of-applied-linguistics/ (adapted)

Text 1

Youth and Adult Literacy in Brazil:

learning from practice

The Concept of functional ILLITERACY

[…] A person is considered functionally literate ..................... he or she is capable ................. using reading and writing skills ........................ meet the demands of his or her social context, using them to continue learning and developing over their lifetimes. With the expansion of the access to schooling beyond literacy, the focus was shifted to the quality of the educational process offered to all. The issue here is not simply whether people know how to read or write, but what they are capable of doing with those skills. This means that, besides the issue of illiteracy, a social problem that still persists in Brazil, there is also the issue of functional illiteracy; in other words, the inability to effectively use reading and writing skills in the various areas of social life after a certain number of years of schooling. According to census criteria, individuals with less than 4 years of schooling are considered functionally illiterate. […]

Source: https://unesdoc.unesco.org

Study these sentences below and decide if they are true ( T ) or false ( F ), according to structure and use of grammar and lexical aspects of language use.

( ) The words in bold, them and their in text 1, are respectively an object pronoun and a possessive adjective.

( ) In the sentence: The issue here is not simply whether people know how to read or write… the underlined word whether can be replaced by if without changing its meaning.

( ) The noun criteria in: According to census criteria, individuals with less than 4 years of schooling are considered functionally illiterate; is the singular form of criterium.

( ) In the following sentence from text 1: … the inability to effectively use reading and writing skills in the various areas of social life after a certain number of years of schooling; the underlined words reading, writing and schooling are examples of present participle.

Choose the alternative which presents the correct sequence, from top to bottom.