Questões de Concurso Público IBGE 2016 para Tecnologista - Estatística

Foram encontradas 70 questões

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large body of data that weren’t possible when working with smaller amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voice-recognition and translation, for example) that work well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March, prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the number of cases for four years running, compared with reported data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit. First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored. That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data "hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends analysis with CDC’s data improved the overall forecast—showing that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the classic hype cycle, in which a technology’s early proponents make overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data’s turn to face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201 4/04/economist-explains-10)

Com a finalidade de estimar a proporção p de indivíduos de certa

população, com determinado atributo, através da proporção

amostral  é extraída uma amostra de tamanho n, grande,

compatível com um erro amostral de ɛ e com um grau de

confiança de (1-α). Assim, é correto afirmar que:

é extraída uma amostra de tamanho n, grande,

compatível com um erro amostral de ɛ e com um grau de

confiança de (1-α). Assim, é correto afirmar que:

As principais medidas de dispersão utilizadas na estatística são a amplitude (A), a variância (Var), o desvio padrão (DP), o coeficiente de variação (CV) e o desvio-interquartílico (DI).

Sobre o tema, é correto afirmar que:

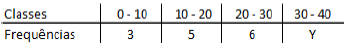

Considere a distribuição de frequências abaixo, apresentada de forma incompleta, sabendo-se não haver valores iguais aos extremos dos intervalos de classe.

Entretanto, antes de se perder o registro de Y, e trabalhando

sempre com os dados grupados, a média da distribuição foi

calculada, sendo igual a 25. Apesar disso, é correto afirmar que:

Sejam X, Z e W variáveis aleatórias tais que, Var (W) = 16, ρ(X,Z) = 1, Var (3.Z + 2 .X) = 144, Cov(W,Z) = 4 e ρ(W,Z)=0,5.

Então a variância de X é:

Considere a variável aleatória bidimensional (X,Y) cuja função de densidade conjunta é dada por:

fx,y(x,y) = 3/4. y.x2,0 < x < 2 e 0 < y < 1 e zero caso contrário. Então: