Questões de Concurso

Para fiscal

Foram encontradas 7.955 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

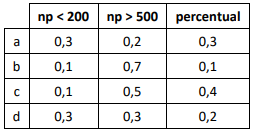

A tabela a seguir apresenta os percentuais de livros com menos de duzentas páginas e percentuais de livros com mais de 500 páginas para cada uma das categorias a, b, c e d. A tabela mostra ainda o percentual de livros de cada uma das 4 categorias.

O percentual de livros da biblioteca com um número de páginas entre 200 e 500 situa-se entre

O número mínimo de quadrados que se obtém dessa forma é igual a

Nesse caso, a probabilidade de que Ana consiga ir à praia no fim de semana sem pegar chuva é de

Eles pretendem fazer um jogo honesto. Se perder, Edson pagará a Roberto 10 reais.

Então, se perder, Roberto deverá pagar a Edson

I. The soil on which the port is being built was once parched. II. The industry is quite diffident about the success of the investment. III. From an international viewpoint the project described will have sweeping implications.

Choose the correct answer:

Text I

Trust and audit

Trust is what auditors sell. They review the accuracy, adequacy or propriety of other people’s work. Financial statement audits are prepared for the owners of a company and presented publically to provide assurance to the market and the wider public. Public service audits are presented to governing bodies and, in some cases, directly to parliament.

It is the independent scepticism of the auditor that allows shareholders and the public to be confident that they are being given a true and fair account of the organisation in question. The auditor’s signature pledges his or her reputational capital so that the audited body’s public statements can be trusted. […]

Given the fundamental importance of trust, should auditors not then feel immensely valuable in the context of declining trust? Not so. Among our interviewees, a consensus emerged that the audit profession is under-producing trust at a critical time. One aspect of the problem is the quietness of audit: it is a profession that literally goes about its work behind the scenes. The face and processes of the auditor are rarely seen in the organisations they scrutinise, and relatively rarely in the outside world. Yet, if we listen to the mounting evidence of the importance of social capital, we know that frequent and reliable contacts between groups are important to strengthening and expanding trust.

So what can be done? Our research suggests that more frequent dialogue with audit committees and a more ambitious outward facing role for the sector’s leadership would be welcome. But we think more is needed. Audit for the 21st century should be understood and designed as primarily a confidence building process within the audited organisation and across its stakeholders. If the audit is a way of ensuring the client’s accountability, much more needs to be done to make the audit itself exemplary in its openness and inclusiveness.

Instead of an audit report being a trust-producing product, the audit process could become a trust-producing practice in which the auditor uses his or her position as a trusted intermediary to broker rigorous learning across all dimensions of the organisation and its stakeholders. The views of investors, staff, suppliers and customers could routinely be considered, as could questions from the general public; online technologies offer numerous opportunities to inform, involve and invite.

From being a service that consists almost exclusively of external investigation by a warranted professional, auditing needs to become more co-productive, with the auditor’s role expanding to include that of an expert convenor who is willing to share the tools of enquiry. Audit could move from ‘black box’ to ‘glass box’.

But the profession will still struggle to secure trust unless it can stake a stronger claim to supporting improvement. Does it increase the economic, social or environmental value of the organisations it reviews? It is one thing to believe in the accuracy of a financial statement audit, but it is another thing to believe in its utility.

Adapted from: https://auditfutures.net/pdf/AuditFutures-RSA-EnlighteningProfessions.pdf

Text I

Trust and audit

Trust is what auditors sell. They review the accuracy, adequacy or propriety of other people’s work. Financial statement audits are prepared for the owners of a company and presented publically to provide assurance to the market and the wider public. Public service audits are presented to governing bodies and, in some cases, directly to parliament.

It is the independent scepticism of the auditor that allows shareholders and the public to be confident that they are being given a true and fair account of the organisation in question. The auditor’s signature pledges his or her reputational capital so that the audited body’s public statements can be trusted. […]

Given the fundamental importance of trust, should auditors not then feel immensely valuable in the context of declining trust? Not so. Among our interviewees, a consensus emerged that the audit profession is under-producing trust at a critical time. One aspect of the problem is the quietness of audit: it is a profession that literally goes about its work behind the scenes. The face and processes of the auditor are rarely seen in the organisations they scrutinise, and relatively rarely in the outside world. Yet, if we listen to the mounting evidence of the importance of social capital, we know that frequent and reliable contacts between groups are important to strengthening and expanding trust.

So what can be done? Our research suggests that more frequent dialogue with audit committees and a more ambitious outward facing role for the sector’s leadership would be welcome. But we think more is needed. Audit for the 21st century should be understood and designed as primarily a confidence building process within the audited organisation and across its stakeholders. If the audit is a way of ensuring the client’s accountability, much more needs to be done to make the audit itself exemplary in its openness and inclusiveness.

Instead of an audit report being a trust-producing product, the audit process could become a trust-producing practice in which the auditor uses his or her position as a trusted intermediary to broker rigorous learning across all dimensions of the organisation and its stakeholders. The views of investors, staff, suppliers and customers could routinely be considered, as could questions from the general public; online technologies offer numerous opportunities to inform, involve and invite.

From being a service that consists almost exclusively of external investigation by a warranted professional, auditing needs to become more co-productive, with the auditor’s role expanding to include that of an expert convenor who is willing to share the tools of enquiry. Audit could move from ‘black box’ to ‘glass box’.

But the profession will still struggle to secure trust unless it can stake a stronger claim to supporting improvement. Does it increase the economic, social or environmental value of the organisations it reviews? It is one thing to believe in the accuracy of a financial statement audit, but it is another thing to believe in its utility.

Adapted from: https://auditfutures.net/pdf/AuditFutures-RSA-EnlighteningProfessions.pdf

Text I

Trust and audit

Trust is what auditors sell. They review the accuracy, adequacy or propriety of other people’s work. Financial statement audits are prepared for the owners of a company and presented publically to provide assurance to the market and the wider public. Public service audits are presented to governing bodies and, in some cases, directly to parliament.

It is the independent scepticism of the auditor that allows shareholders and the public to be confident that they are being given a true and fair account of the organisation in question. The auditor’s signature pledges his or her reputational capital so that the audited body’s public statements can be trusted. […]

Given the fundamental importance of trust, should auditors not then feel immensely valuable in the context of declining trust? Not so. Among our interviewees, a consensus emerged that the audit profession is under-producing trust at a critical time. One aspect of the problem is the quietness of audit: it is a profession that literally goes about its work behind the scenes. The face and processes of the auditor are rarely seen in the organisations they scrutinise, and relatively rarely in the outside world. Yet, if we listen to the mounting evidence of the importance of social capital, we know that frequent and reliable contacts between groups are important to strengthening and expanding trust.

So what can be done? Our research suggests that more frequent dialogue with audit committees and a more ambitious outward facing role for the sector’s leadership would be welcome. But we think more is needed. Audit for the 21st century should be understood and designed as primarily a confidence building process within the audited organisation and across its stakeholders. If the audit is a way of ensuring the client’s accountability, much more needs to be done to make the audit itself exemplary in its openness and inclusiveness.

Instead of an audit report being a trust-producing product, the audit process could become a trust-producing practice in which the auditor uses his or her position as a trusted intermediary to broker rigorous learning across all dimensions of the organisation and its stakeholders. The views of investors, staff, suppliers and customers could routinely be considered, as could questions from the general public; online technologies offer numerous opportunities to inform, involve and invite.

From being a service that consists almost exclusively of external investigation by a warranted professional, auditing needs to become more co-productive, with the auditor’s role expanding to include that of an expert convenor who is willing to share the tools of enquiry. Audit could move from ‘black box’ to ‘glass box’.

But the profession will still struggle to secure trust unless it can stake a stronger claim to supporting improvement. Does it increase the economic, social or environmental value of the organisations it reviews? It is one thing to believe in the accuracy of a financial statement audit, but it is another thing to believe in its utility.

Adapted from: https://auditfutures.net/pdf/AuditFutures-RSA-EnlighteningProfessions.pdf

Text I

Trust and audit

Trust is what auditors sell. They review the accuracy, adequacy or propriety of other people’s work. Financial statement audits are prepared for the owners of a company and presented publically to provide assurance to the market and the wider public. Public service audits are presented to governing bodies and, in some cases, directly to parliament.

It is the independent scepticism of the auditor that allows shareholders and the public to be confident that they are being given a true and fair account of the organisation in question. The auditor’s signature pledges his or her reputational capital so that the audited body’s public statements can be trusted. […]

Given the fundamental importance of trust, should auditors not then feel immensely valuable in the context of declining trust? Not so. Among our interviewees, a consensus emerged that the audit profession is under-producing trust at a critical time. One aspect of the problem is the quietness of audit: it is a profession that literally goes about its work behind the scenes. The face and processes of the auditor are rarely seen in the organisations they scrutinise, and relatively rarely in the outside world. Yet, if we listen to the mounting evidence of the importance of social capital, we know that frequent and reliable contacts between groups are important to strengthening and expanding trust.

So what can be done? Our research suggests that more frequent dialogue with audit committees and a more ambitious outward facing role for the sector’s leadership would be welcome. But we think more is needed. Audit for the 21st century should be understood and designed as primarily a confidence building process within the audited organisation and across its stakeholders. If the audit is a way of ensuring the client’s accountability, much more needs to be done to make the audit itself exemplary in its openness and inclusiveness.

Instead of an audit report being a trust-producing product, the audit process could become a trust-producing practice in which the auditor uses his or her position as a trusted intermediary to broker rigorous learning across all dimensions of the organisation and its stakeholders. The views of investors, staff, suppliers and customers could routinely be considered, as could questions from the general public; online technologies offer numerous opportunities to inform, involve and invite.

From being a service that consists almost exclusively of external investigation by a warranted professional, auditing needs to become more co-productive, with the auditor’s role expanding to include that of an expert convenor who is willing to share the tools of enquiry. Audit could move from ‘black box’ to ‘glass box’.

But the profession will still struggle to secure trust unless it can stake a stronger claim to supporting improvement. Does it increase the economic, social or environmental value of the organisations it reviews? It is one thing to believe in the accuracy of a financial statement audit, but it is another thing to believe in its utility.

Adapted from: https://auditfutures.net/pdf/AuditFutures-RSA-EnlighteningProfessions.pdf

I. In auditing, taking heed of what other parties have to say needs to be downplayed. II. Auditors are generally unobtrusive when carrying out their jobs. III. Trust is obtained when auditors eschew straightforward statements.

The statements are, respectively,

“Segundo o Art. 6º da Lei nº 10.593/2002 é atribuição dos ocupantes do cargo de Auditor-Fiscal da Receita Federal do Brasil: elaborar e proferir decisões ou delas participar em processo administrativo-fiscal, bem como em processos de consulta, restituição ou compensação de tributos e contribuições e de reconhecimento de benefícios fiscais.”

A elaboração de um texto supõe cuidados com aspectos diversos. Sobre a estruturação desse pequeno segmento textual, assinale a afirmativa correta.

Essa é uma afirmação de um fiscal de prova, que é formulada, passando de uma premissa diretamente a uma conclusão, assumindo como verdadeira uma ideia intermediária.

Assinale a opção que indica corretamente a ideia intermediária omitida.

“Não bastasse a complexidade existente, todos os dias são criadas mais 46 leis tributárias - Desde a promulgação da Constituição de 1988, o Brasil criou 320.343 leis tributárias. Sim: trezentos e vinte mil, trezentos e quarenta e três leis tributárias. Levando-se em conta o número de dias úteis no período, foram criadas 46 novas leis todos os dias, segundo um levantamento do IBPT. Se continuarmos nesse ritmo, nossa complexidade tributária só tende a piorar e complicar ainda mais os negócios do país, que já precisam seguir 40.865 artigos legais para poderem funcionar.”

O fato citado é considerado “impressionante” pelo autor do texto em função

“Por exemplo no trânsito: Se o governo não quer que ultrapassemos certo limite de velocidade numa estrada, começa a aplicar multas para quem o ultrapassa. Como o dinheiro é a verdadeira linguagem universal, aquela que todos entendem em qualquer lugar do mundo, então de fato os motoristas começam a respeitar o limite de velocidade.”

Acerca desse segmento textual, assinale a afirmativa correta.

O imposto de renda e a economia do desincentivo (Ronaud.com)

O texto acima se insere entre os textos argumentativos. Uma das marcas desses textos é a necessidade de coerência lógica.

Assinale a opção em que a frase dada mostra incoerência.