Questões de Concurso

Comentadas para analista de banco de dados

Foram encontradas 1.285 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

I. Pessoa ou grupo que fornece os recursos financeiros para o projeto.

II. Pessoas que estejam ativamente envolvidas no gerenciamento ou na execução do projeto.

III. Pessoas e organizações cujos interesses possam ser afetados de forma positiva pelo projeto.

IV. Pessoas e organizações cujos interesses possam ser afetados de forma negativa pelo projeto.

É considerado stakeholder o que consta em

Apps include everything from games to specialized word processors and even instruments. Generally, apps make use of a tablet's touchscreen to deliver an experience that a user couldn't get from a typical computer.

Sobre o texto acima, é INCORRETO afirmar:

A rainha má mandou chamar um lenhador e instruiu-o a levar Branca de Neve para a floresta, matá-la, desfazer-se do corpo e voltar para ganhar sua recompensa. Mas o lenhador poupou Branca de Neve. Toda a história depende da compaixão de um lenhador sobre o qual não se sabe nada. Seu nome e sua biografia não constam em nenhuma versão do conto. A rainha má é a rainha má, claramente um arquétipo, e os arquétipos não precisam de nome. O Príncipe Encantado, que aparecerá no fim da história, também não precisa. É um símbolo reincidente, talvez nem a Branca de Neve se dê ao trabalho de descobrir seu nome. Mas o personagem principal da história, sem o qual a história não existiria e os outros personagens não se tornariam famosos, não é símbolo de nada. Ele só entra na trama para fazer uma escolha, mas toda a narrativa fica em suspenso até que ele faça a escolha certa, pois se fizer a errada não tem história. O lenhador compadecido representa dois segundos de livre-arbítrio que podem desregular o mundo dos deuses e dos heróis. Por isso é desprezado como qualquer intruso e nem aparece nos créditos.

Muitas histórias mostram como são os figurantes anônimos que fazem a história, ou como, no fim, é a boa consciência que move o mundo. Mas uma das pessoas do grupo em que conversávamos sobre esses anônimos discordou dessa tese, e disse que a entrada do lenhador simbolizava um problema da humanidade, que é a dificuldade de conseguir empregados de confiança, que façam o que lhes for pedido.

(Adaptado de Luiz Fernando Verissimo, Banquete com os deuses)

A rainha má mandou chamar um lenhador e instruiu-o a levar Branca de Neve para a floresta, matá-la, desfazer-se do corpo e voltar para ganhar sua recompensa. Mas o lenhador poupou Branca de Neve. Toda a história depende da compaixão de um lenhador sobre o qual não se sabe nada. Seu nome e sua biografia não constam em nenhuma versão do conto. A rainha má é a rainha má, claramente um arquétipo, e os arquétipos não precisam de nome. O Príncipe Encantado, que aparecerá no fim da história, também não precisa. É um símbolo reincidente, talvez nem a Branca de Neve se dê ao trabalho de descobrir seu nome. Mas o personagem principal da história, sem o qual a história não existiria e os outros personagens não se tornariam famosos, não é símbolo de nada. Ele só entra na trama para fazer uma escolha, mas toda a narrativa fica em suspenso até que ele faça a escolha certa, pois se fizer a errada não tem história. O lenhador compadecido representa dois segundos de livre-arbítrio que podem desregular o mundo dos deuses e dos heróis. Por isso é desprezado como qualquer intruso e nem aparece nos créditos.

Muitas histórias mostram como são os figurantes anônimos que fazem a história, ou como, no fim, é a boa consciência que move o mundo. Mas uma das pessoas do grupo em que conversávamos sobre esses anônimos discordou dessa tese, e disse que a entrada do lenhador simbolizava um problema da humanidade, que é a dificuldade de conseguir empregados de confiança, que façam o que lhes for pedido.

(Adaptado de Luiz Fernando Verissimo, Banquete com os deuses)

A rainha má mandou chamar um lenhador e instruiu-o a levar Branca de Neve para a floresta, matá-la, desfazer-se do corpo e voltar para ganhar sua recompensa. Mas o lenhador poupou Branca de Neve. Toda a história depende da compaixão de um lenhador sobre o qual não se sabe nada. Seu nome e sua biografia não constam em nenhuma versão do conto. A rainha má é a rainha má, claramente um arquétipo, e os arquétipos não precisam de nome. O Príncipe Encantado, que aparecerá no fim da história, também não precisa. É um símbolo reincidente, talvez nem a Branca de Neve se dê ao trabalho de descobrir seu nome. Mas o personagem principal da história, sem o qual a história não existiria e os outros personagens não se tornariam famosos, não é símbolo de nada. Ele só entra na trama para fazer uma escolha, mas toda a narrativa fica em suspenso até que ele faça a escolha certa, pois se fizer a errada não tem história. O lenhador compadecido representa dois segundos de livre-arbítrio que podem desregular o mundo dos deuses e dos heróis. Por isso é desprezado como qualquer intruso e nem aparece nos créditos.

Muitas histórias mostram como são os figurantes anônimos que fazem a história, ou como, no fim, é a boa consciência que move o mundo. Mas uma das pessoas do grupo em que conversávamos sobre esses anônimos discordou dessa tese, e disse que a entrada do lenhador simbolizava um problema da humanidade, que é a dificuldade de conseguir empregados de confiança, que façam o que lhes for pedido.

(Adaptado de Luiz Fernando Verissimo, Banquete com os deuses)

Refaz-se a redação da frase acima, mantendo-se a correção, a clareza e a coerência em:

administração pública.

respeito de probabilidade e contagem, seguida de uma assertiva a ser

julgada.

respeito de probabilidade e contagem, seguida de uma assertiva a ser

julgada.

A: Para todo evento probabilístico X, a probabilidade P(X) é tal que 0 ≤ P(X) ≤ 1.

Nesse caso, o conjunto verdade da proposição ¬ A tem infinitos elementos.

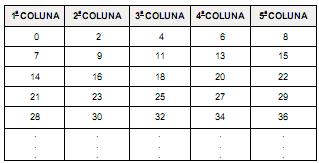

Se esse padrão fosse mantido indefinidamente, qual dos números seguintes com certeza NÃO estaria nessa tabela?

Harry McCracken, PC World

Monday, October 19, 2009 10:00 AM PDT

Reading about a new operating system can tell you only so much about it: After all, Windows Vista had far more features than XP, [CONJUNCTION] fell far short of it in the eyes of many users. To judge an OS accurately, you have to live with it. Over the past ten months, I've spent a substantial percentage of my computing life in Windows 7, starting with a preliminary version and culminating in recent weeks with the final Release to Manufacturing edition. I've run it on systems ranging from an underpowered Asus EeePC 1000HE netbook to a potent HP TouchSmart all-in-one. And I've used it to do real work, not lab routines. Usually, I've run the OS in multiboot configurations with Windows Vista and/or XP, so I've had a choice each time I turned the computer on: [MODAL] I opt for Windows 7 or an

older version of the OS? The call has been easy to make, because Win 7 is so pleasant to use.

So why wouldn't you want to run this operating system? Concern over its performance is one logical reason, especially since early versions of Windows Vista managed to turn PCs that ran XP with ease into lethargic underperformers. The PC World Test Center's speed benchmarks on five test PCs showed Windows 7 to be faster than Vista, but only by a little; I've found it to be reasonably quick on every computer I've used it on - even the Asus netbook, once I upgraded it to 2GB of RAM. (Our lab tried Win 7 on a Lenovo S10 netbook with 1GB of RAM and found it to be a shade slower than XP; for details see "Windows 7 Performance Tests.").

Here's a rule of thumb that errs on the side of caution: If your PC's specs qualify it to run Vista, get Windows 7; if they don't, avoid it. Microsoft's official hardware configuration requirements for Windows 7 are nearly identical to those it recommends for Windows Vista: a 1-GHz CPU, 1GB of RAM,

16GB of free disk space, and a DirectX 9-compatible graphics device with a WDDM 1.0 or higher driver. That's for the 32-bit version of Windows 7; the 64-bit version of the OS requires a 64-bit CPU, 2GB of RAM, and 20GB of disk space.

Fear of incompatible hardware and software is another understandable reason to be wary of Windows 7. One unfortunate law of operating-system upgrades - which applies equally to Macs and to Windows PCs - is that they will break some systems and applications, especially at first.

Under the hood, Windows 7 isn't radically different from Vista. That's a plus, since it should greatly reduce the volume of difficulties relating to drivers and apps compared to Vista's bumpy rollout. I have performed a half-dozen Windows 7 upgrades, and most of them went off without a hitch. The

gnarliest problem arose when I had to track down a graphics driver for Dell's XPS M1330 laptop on my own - Windows 7 installed a generic VGA driver that couldn't run the Aero user interface, and as a result failed to support new Windows 7 features such as thumbnail views in the Taskbar.

The best way to reduce your odds of running into a showstopping problem with Windows 7 is to bide your time. When the new operating system arrives on October 22, sit back and let the earliest adopters discover the worst snafus. Within a few weeks, Microsoft and other software and hardware companies will have fixed most of them, and your chances of a happy migration to Win 7 will be much higher. If you want to be really conservative, hold off on moving to Win 7 until you're ready to buy a PC that's designed to run it well.

Waiting a bit before making the leap makes sense; waiting forever does not. Microsoft took far too long to come up with a satisfactory replacement for Windows XP. But whether you choose to install Windows 7 on your current systems or get it on the next new PC you buy, you'll find that it's the unassuming, thoroughly practical upgrade you've been waiting for ? flaws and all.

(Adapted from http://www.pcworld.com/article/172602/windows_7_revi...)

Harry McCracken, PC World

Monday, October 19, 2009 10:00 AM PDT

Reading about a new operating system can tell you only so much about it: After all, Windows Vista had far more features than XP, [CONJUNCTION] fell far short of it in the eyes of many users. To judge an OS accurately, you have to live with it. Over the past ten months, I've spent a substantial percentage of my computing life in Windows 7, starting with a preliminary version and culminating in recent weeks with the final Release to Manufacturing edition. I've run it on systems ranging from an underpowered Asus EeePC 1000HE netbook to a potent HP TouchSmart all-in-one. And I've used it to do real work, not lab routines. Usually, I've run the OS in multiboot configurations with Windows Vista and/or XP, so I've had a choice each time I turned the computer on: [MODAL] I opt for Windows 7 or an

older version of the OS? The call has been easy to make, because Win 7 is so pleasant to use.

So why wouldn't you want to run this operating system? Concern over its performance is one logical reason, especially since early versions of Windows Vista managed to turn PCs that ran XP with ease into lethargic underperformers. The PC World Test Center's speed benchmarks on five test PCs showed Windows 7 to be faster than Vista, but only by a little; I've found it to be reasonably quick on every computer I've used it on - even the Asus netbook, once I upgraded it to 2GB of RAM. (Our lab tried Win 7 on a Lenovo S10 netbook with 1GB of RAM and found it to be a shade slower than XP; for details see "Windows 7 Performance Tests.").

Here's a rule of thumb that errs on the side of caution: If your PC's specs qualify it to run Vista, get Windows 7; if they don't, avoid it. Microsoft's official hardware configuration requirements for Windows 7 are nearly identical to those it recommends for Windows Vista: a 1-GHz CPU, 1GB of RAM,

16GB of free disk space, and a DirectX 9-compatible graphics device with a WDDM 1.0 or higher driver. That's for the 32-bit version of Windows 7; the 64-bit version of the OS requires a 64-bit CPU, 2GB of RAM, and 20GB of disk space.

Fear of incompatible hardware and software is another understandable reason to be wary of Windows 7. One unfortunate law of operating-system upgrades - which applies equally to Macs and to Windows PCs - is that they will break some systems and applications, especially at first.

Under the hood, Windows 7 isn't radically different from Vista. That's a plus, since it should greatly reduce the volume of difficulties relating to drivers and apps compared to Vista's bumpy rollout. I have performed a half-dozen Windows 7 upgrades, and most of them went off without a hitch. The

gnarliest problem arose when I had to track down a graphics driver for Dell's XPS M1330 laptop on my own - Windows 7 installed a generic VGA driver that couldn't run the Aero user interface, and as a result failed to support new Windows 7 features such as thumbnail views in the Taskbar.

The best way to reduce your odds of running into a showstopping problem with Windows 7 is to bide your time. When the new operating system arrives on October 22, sit back and let the earliest adopters discover the worst snafus. Within a few weeks, Microsoft and other software and hardware companies will have fixed most of them, and your chances of a happy migration to Win 7 will be much higher. If you want to be really conservative, hold off on moving to Win 7 until you're ready to buy a PC that's designed to run it well.

Waiting a bit before making the leap makes sense; waiting forever does not. Microsoft took far too long to come up with a satisfactory replacement for Windows XP. But whether you choose to install Windows 7 on your current systems or get it on the next new PC you buy, you'll find that it's the unassuming, thoroughly practical upgrade you've been waiting for ? flaws and all.

(Adapted from http://www.pcworld.com/article/172602/windows_7_revi...)

Harry McCracken, PC World

Monday, October 19, 2009 10:00 AM PDT

Reading about a new operating system can tell you only so much about it: After all, Windows Vista had far more features than XP, [CONJUNCTION] fell far short of it in the eyes of many users. To judge an OS accurately, you have to live with it. Over the past ten months, I've spent a substantial percentage of my computing life in Windows 7, starting with a preliminary version and culminating in recent weeks with the final Release to Manufacturing edition. I've run it on systems ranging from an underpowered Asus EeePC 1000HE netbook to a potent HP TouchSmart all-in-one. And I've used it to do real work, not lab routines. Usually, I've run the OS in multiboot configurations with Windows Vista and/or XP, so I've had a choice each time I turned the computer on: [MODAL] I opt for Windows 7 or an

older version of the OS? The call has been easy to make, because Win 7 is so pleasant to use.

So why wouldn't you want to run this operating system? Concern over its performance is one logical reason, especially since early versions of Windows Vista managed to turn PCs that ran XP with ease into lethargic underperformers. The PC World Test Center's speed benchmarks on five test PCs showed Windows 7 to be faster than Vista, but only by a little; I've found it to be reasonably quick on every computer I've used it on - even the Asus netbook, once I upgraded it to 2GB of RAM. (Our lab tried Win 7 on a Lenovo S10 netbook with 1GB of RAM and found it to be a shade slower than XP; for details see "Windows 7 Performance Tests.").

Here's a rule of thumb that errs on the side of caution: If your PC's specs qualify it to run Vista, get Windows 7; if they don't, avoid it. Microsoft's official hardware configuration requirements for Windows 7 are nearly identical to those it recommends for Windows Vista: a 1-GHz CPU, 1GB of RAM,

16GB of free disk space, and a DirectX 9-compatible graphics device with a WDDM 1.0 or higher driver. That's for the 32-bit version of Windows 7; the 64-bit version of the OS requires a 64-bit CPU, 2GB of RAM, and 20GB of disk space.

Fear of incompatible hardware and software is another understandable reason to be wary of Windows 7. One unfortunate law of operating-system upgrades - which applies equally to Macs and to Windows PCs - is that they will break some systems and applications, especially at first.

Under the hood, Windows 7 isn't radically different from Vista. That's a plus, since it should greatly reduce the volume of difficulties relating to drivers and apps compared to Vista's bumpy rollout. I have performed a half-dozen Windows 7 upgrades, and most of them went off without a hitch. The

gnarliest problem arose when I had to track down a graphics driver for Dell's XPS M1330 laptop on my own - Windows 7 installed a generic VGA driver that couldn't run the Aero user interface, and as a result failed to support new Windows 7 features such as thumbnail views in the Taskbar.

The best way to reduce your odds of running into a showstopping problem with Windows 7 is to bide your time. When the new operating system arrives on October 22, sit back and let the earliest adopters discover the worst snafus. Within a few weeks, Microsoft and other software and hardware companies will have fixed most of them, and your chances of a happy migration to Win 7 will be much higher. If you want to be really conservative, hold off on moving to Win 7 until you're ready to buy a PC that's designed to run it well.

Waiting a bit before making the leap makes sense; waiting forever does not. Microsoft took far too long to come up with a satisfactory replacement for Windows XP. But whether you choose to install Windows 7 on your current systems or get it on the next new PC you buy, you'll find that it's the unassuming, thoroughly practical upgrade you've been waiting for ? flaws and all.

(Adapted from http://www.pcworld.com/article/172602/windows_7_revi...)

The bigger the project, the fewer people are demanded.