Questões de Vestibular

Sobre interpretação de texto | reading comprehension em inglês

Foram encontradas 4.863 questões

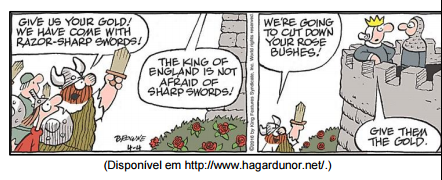

A tirinha ironiza uma suposta característica dos ingleses:

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXTO 7

O mistério dos hippies desaparecidos

Ide ao Mercadão da Travessa do Carmo. Que vereis? O alegre, o pitoresco, o colorido. Admirai a excelente organização: cada artesão em seu quadrado, exibindo belos trabalhos.

Mas... Nada vos chama a atenção?

Não? Neste caso, pergunto-vos: onde estão os hippies da Praça Dom Feliciano? Isso mesmo, aqueles que ficavam na frente da Santa Casa. Onde estão? Não sabeis?

O homem de cinza sabe.

O homem de cinza vinha todos os dias à Praça Dom Feliciano. Ficava muito tempo olhando os hippies, que não lhe davam maior atenção. O homem, ao contrário, parecia muito interessado neles: examinava os objetos expostos, indagava por preços, por detalhes da manufatura. E anotava tudo numa caderneta de capa preta. Um dia perguntou aos hippies onde moravam. Por aí, respondeu um rapaz. Numa comuna? — perguntou o homem. Não, não era em nenhuma comuna; na realidade, estavam ao relento. O homem então disse que eles deveriam morar juntos numa comuna. Ficaria mais fácil, mais prático. O rapaz concordou. Não estava com muita vontade de falar; contudo, acrescentou, depois de uma pausa, que o problema era encontrar o lugar para a comuna.

Não é problema, disse o homem; eu tenho uma chácara lá na Vila Nova, com uma boa casa, gramados, árvores frutíferas. Se vocês quiserem, podem ficar lá. No amor? — perguntou o rapaz.

— No amor, bicho — respondeu o homem, rindo. Só quero que vocês tomem conta da casa. Os hippies confabularam entre si e resolveram aceitar. O homem levou-os — eram doze, entre rapazes e moças — à chácara, numa camioneta Veraneio. Deixou-os lá.

Durante algum tempo não apareceu. Mas, num domingo, deu as caras. Conversou com os jovens sobre a chácara, contou histórias interessantes. Finalmente, pediu para ver o que tinham feito de artesanato. Examinou as peças atentamente e disse:

— Posso dar uma sugestão? Eles concordaram. Como não haveriam de concordar? Mas foi assim que começou. O homem organizou-os em equipes: a equipe dos cintos, a equipe das pulseiras, a equipe das bolsas.

Ensinou-os a trabalhar pelo sistema de linha de montagem; racionalizou cada tarefa, cada atividade.

Disciplinou a vida deles, também. Centralizou todo o consumo de tóxicos. Fornecia drogas mediante vales, resgatados ao fim do mês, conforme a produção. Permitiu que se vestissem como desejavam, mas era rígido na escala de trabalho. Seis dias por semana, folga às quartas — nos domingos tinham de trabalhar. Nestes dias, o homem de cinza admitia visitantes na chácara, mediante o pagamento de ingressos. Um guia especialmente treinado acompanhava-os, explicando todos os detalhes acerca dos hippies, estes seres curiosos.

O homem de cinza já era muito rico, mas agora está multimilionário. É que organizou uma firma, e exporta para os Estados Unidos e para o Mercado Comum Europeu cintos, pulseiras e bolsas.

Parece que, para esses artigos, não há sobretaxa de exportações. Escreveu um livro — Minha Vida Entre os Hippies — que tem se constituído em autêntico êxito de livraria; uma adaptação para a televisão, sob forma de novela, está quase pronta. E quem ouviu a trilha sonora, garante que é um estouro.

Tem apenas um temor, este homem. É que um dos hippies, de uma hora para outra, cortou o cabelo, passou a tomar banho — e usa agora um decente terno cinza. Por enquanto ainda não se manifestou; mas trata-se — o homem de cinza está convencido disto — de um autêntico contestador.

(SCLIAR, Moacyr. Melhores contos. São Paulo: Global, 2003.

p. 130-132.)

Match the columns to form statements about “hippies”:

I - They usually sell...

II - They were young people in the 1960s and 1970s who...

III - They try to live...

IV - They often have...

( ) …long hair and many of them take drugs.

( ) …rejected conventional ways of living, dressing, and behaving.

( ) …based on peace and love.

( ) …handcraft.

The right sequence is:

TEXTO 5

É com certa sabedoria que se diz: pelos olhos se conhece uma pessoa. Bem, há olhares de todos os tipos — dos dissimulados aos da cobiça, seja pelo vil metal ou pelo sexo.

Garimpeiro se conhece pelos olhos. Olhos de febre, que flamejam e reluzem. Há, em suas pupilas, o ouro. O brilho dourado tatua a íris. Trata-se apenas de um reflexo de sua alma e daquilo que corre em suas veias. É um vírus. A princípio, um sonho distante, mas, ao correr dos dias, torna-se uma angustiante busca. Na primeira vez que o ouro fagulha na sua frente, na bateia, toda a alma se contamina e o vírus se transforma em doença incurável.

Todos, no garimpo, têm histórias semelhantes. Têm família, filhos, empregos em suas cidades, nos distantes estados, mas, de repente, espalha-se a notícia do ouro. Então, largam tudo, vendem a roupa do corpo e lá se vão. Caçar o rastro do ouro é a sina. Nos olhos, a febre — um brilho dourado doentio. Sim, é fácil conhecer um garimpeiro.

Todos sabem que, no garimpo, não é lugar para se viver. Mas ninguém abandona o seu posto. Suor, lama, pedregulhos, pepitas douradas, cansaço — é a vida que até o diabo rejeita.

Por onde passam, o rastro da destruição. A Amazônia é nossa. Tratores e retroescavadeiras derrubam e limpam a floresta; as dragas chegam, os rios se contaminam rapidamente de mercúrio. Quem pode mais chora menos. Na trilha do brilho dourado, nada se preserva. Ai daqueles que levantarem alguma voz... No dia seguinte, o corpo é encontrado no meio da selva, um bom prato aos bichos.

(GONÇALVES, David. Sangue verde. Joinville: Sucesso

Pocket, 2014. p. 5-6. Adaptado.)

TEXTO 3

Escalada para o inferno

Iniciava-se ali, meu estágio no inferno. A ardida solidão corroía cada passo que eu dava. Via crucis vivida aos seis anos de idade, ao sol das duas horas. Vermelhidão por todos os lados daquela rua íngreme e poeirenta. Meus olhos pediam socorro mas só encontravam uma infinitude de terra e desolação. Tentava acompanhar os passos de meu pai. E eles eram enormes. Não só os passos mas as pernas. Meus olhos olhavam duplamente: para os passos e para as pernas e não alcançavam nem um nem outro. Apenas se defrontavam com um vazio empoeirado que entrava no meu ser inteiro. Eu queria chorar mas tinha medo. Tropeçava a cada tentativa de correr para alcançar meu pai. E eu tinha medo de ter medo. E eu tinha medo de chorar. E era um sofrimento com todos os vórtices de agonia. À minha frente, até onde meus olhos conseguiram enxergar, estavam os pés e as pernas de meu pai que iam firmes subindo subindo subindo sem cessar. À minha volta eu podia ver e sentir a terra vermelha e minha vida envolta num turbilhão de desespero. Na verdade eu não sabia muito bem para onde estava indo. Eu era bestializado nos meus próprios passos. Nas minhas próprias pernas. Tinha a impressão que o ponto de chegada era aquele redemoinho em que me encontrava e que dele nunca mais sairia. Na ânsia de ir sem querer ir eu gaguejava no caminhar. E olhava com sofreguidão para os meus pés e via ainda com mais aflição que os bicos de meus sapatos novos estavam sujos daquela poeira impregnante, vasculhante, suja. Eu sempre gostei de sapatos. Eu sempre gostei de sapatos novos. Novos e luzidios. E eles estavam sujos. Cobertos de poeira. E a subida prosseguia inalterada. Tentava olhar para o alto e só conseguia ver os enormes joelhos de meu pai que dobravam num ritmo compassado. Via suas pernas e seus pés. E só. Sentia, lá no fundo, um desejo calado de dizer alguma coisa. De dizer-lhe que parasse. Que fosse mais devagar. Que me amparasse. Mas esse desejo era um calo na minha pequenina garganta que jamais seria curado. E eu prossegui ao extremo de meus limites. Tinha de acontecer: desamarrou o cadarço de meu sapato. A loucura do sol das duas horas parece ter se engraçado pelo meu desatino. Tudo ficou muito mais quente. Tudo ficou mais empoeirado e muito mais vermelho. O desatino me levou ao choro. Não sei se chorei ou se choraminguei. Só sei que dei índices de que eu precisava de meu pai. E ele atendeu. Voltou-se para mim e viu que estava pisando no cadarço. Que estava prestes a cair. Então me socorreu. Olhou-me nos olhos com a expressão casmurra. Levou suas enormes mãos aos meus pés e amarrou o cadarço firmemente com um intrincado nó. A cena me levou a um estado de cegueira anestésica tão intensa que sofri uma espécie de amnésia passageira. Estado de torpor. Quando dei por mim, já tinha chegado ao meu destino: cadeira do barbeiro. Alta, prepotente e giratória. Ele, o barbeiro, cabeça enorme, mãos enormes, enormes unhas, sorriso nos lábios dos quais surgiam grandes caninos. Ele portava enorme máquina que apontava em minha direção. E ouvi a voz do pai: pode tirar quase tudo! deixa só um pouco em cima! Ali, finalmente, para lembrar Rimbaud, ia se encerrar meu estágio no inferno.

(GONÇALVES, Aguinaldo. Das estampas. São Paulo: Nankin, 2013. p. 45-46.)

TEXTO PARA A QUESTÃO

A study carried out by Lauren Sherman of the University of California and her colleagues investigated how use of the “like” button in social media affects the brains of teenagers lying in body scanners.

Thirty-two teens who had Instagram accounts were asked to lie down in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner. This let Dr. Sherman monitor their brain activity while they were perusing both their own Instagram photos and photos that they were told had been added by other teenagers in the experiment. In reality, Dr. Sherman had collected all the other photos, which included neutral images of food and friends as well as many depicting risky behaviours like drinking, smoking and drug use, from other peoples’ Instagram accounts. The researchers told participants they were viewing photographs that 50 other teenagers had already seen and endorsed with a “like” in the laboratory.

The participants were more likely themselves to “like” photos already depicted as having been “liked” a lot than they were photos depicted with fewer previous “likes”. When she looked at the fMRI results, Dr. Sherman found that activity in the nucleus accumbens, a hub of reward circuitry in the brain, increased with the number of “likes” that a photo had.

The Economist, June 13, 2016. Adaptado.

TEXTO PARA A QUESTÃO

A study carried out by Lauren Sherman of the University of California and her colleagues investigated how use of the “like” button in social media affects the brains of teenagers lying in body scanners.

Thirty-two teens who had Instagram accounts were asked to lie down in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner. This let Dr. Sherman monitor their brain activity while they were perusing both their own Instagram photos and photos that they were told had been added by other teenagers in the experiment. In reality, Dr. Sherman had collected all the other photos, which included neutral images of food and friends as well as many depicting risky behaviours like drinking, smoking and drug use, from other peoples’ Instagram accounts. The researchers told participants they were viewing photographs that 50 other teenagers had already seen and endorsed with a “like” in the laboratory.

The participants were more likely themselves to “like” photos already depicted as having been “liked” a lot than they were photos depicted with fewer previous “likes”. When she looked at the fMRI results, Dr. Sherman found that activity in the nucleus accumbens, a hub of reward circuitry in the brain, increased with the number of “likes” that a photo had.

The Economist, June 13, 2016. Adaptado.

TEXTO PARA A QUESTÃO

Plants not only remember when you touch them, but they can also make risky decisions that are as sophisticated as those made by humans, all without brains or complex nervous systems.

Researchers showed that when faced with the choice between a pot containing constant levels of nutrients or one with unpredictable levels, a plant will pick the mystery pot when conditions are sufficiently poor.

In a set of experiments, Dr. Shemesh, from Tel✄Hai College in Israel, and Alex Kacelnik, from Oxford University, grew pea plants and split their roots between two pots. Both pots had the same amount of nutrients on average, but in one, the levels were constant; in the other, they varied over time. Then the researchers switched the conditions so that the average nutrients in both pots would be equally high or low, and asked: Which pot would a plant prefer?

When nutrient levels were low, the plants laid more roots in the unpredictable pot. But when nutrients were abundant, they chose the one that always had the same amount.

The New York Times, June 30, 2016. Adaptado.

TEXTO PARA A QUESTÃO

Plants not only remember when you touch them, but they can also make risky decisions that are as sophisticated as those made by humans, all without brains or complex nervous systems.

Researchers showed that when faced with the choice between a pot containing constant levels of nutrients or one with unpredictable levels, a plant will pick the mystery pot when conditions are sufficiently poor.

In a set of experiments, Dr. Shemesh, from Tel✄Hai College in Israel, and Alex Kacelnik, from Oxford University, grew pea plants and split their roots between two pots. Both pots had the same amount of nutrients on average, but in one, the levels were constant; in the other, they varied over time. Then the researchers switched the conditions so that the average nutrients in both pots would be equally high or low, and asked: Which pot would a plant prefer?

When nutrient levels were low, the plants laid more roots in the unpredictable pot. But when nutrients were abundant, they chose the one that always had the same amount.

The New York Times, June 30, 2016. Adaptado.

TEXTO PARA A QUESTÃO

Plants not only remember when you touch them, but they can also make risky decisions that are as sophisticated as those made by humans, all without brains or complex nervous systems.

Researchers showed that when faced with the choice between a pot containing constant levels of nutrients or one with unpredictable levels, a plant will pick the mystery pot when conditions are sufficiently poor.

In a set of experiments, Dr. Shemesh, from Tel✄Hai College in Israel, and Alex Kacelnik, from Oxford University, grew pea plants and split their roots between two pots. Both pots had the same amount of nutrients on average, but in one, the levels were constant; in the other, they varied over time. Then the researchers switched the conditions so that the average nutrients in both pots would be equally high or low, and asked: Which pot would a plant prefer?

When nutrient levels were low, the plants laid more roots in the unpredictable pot. But when nutrients were abundant, they chose the one that always had the same amount.

The New York Times, June 30, 2016. Adaptado.

A new planet in our neighborhood - how likely is life there?

By Don Lincoln, August 24, 2016

Scientists working at the European Southern Observatory (ESO), using the La Silla telescope, claim to have discovered the closest exoplanet to Earth. Exoplanet means planets orbiting stars other than the Sun. Most of them are huge planets orbiting very near their star. The newly discovered planet, which orbits Proxima Centauri, a star within the so-called “habitable zone”, has been named Proxima b.

Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf, which is the most common type of star in the galaxy. Red dwarfs are much smaller than our Sun, and are very dim. For instance, in the visible spectrum that we use to see, Proxima Centauri gives off 0.0056% as much light as the Sun.

So what about life? Are there any chances that an alien lizard might bask in Proxima Centauri’s light or try to find shade under an alien tree? Dr. Guillem Anglada-Escudé, co-author of the research from London University, believes that “there is a reasonable expectation that this planet might be able to host life”

But this belief is not consensual as other scientists think the prospect of life is improbable. Although the temperature of the planet is thought to be such that liquid water could exist, it is unlikely that Proxima b is habitable, as the planet is subject to stellar wind pressures of more than 2000 times those experienced by Earth from the solar wind. These winds would likely blow any atmosphere away, leaving the undersurface as the only vaguely habitable location on that planet. You shouldn’t imagine, thus, a lush and verdant world, with lovely blue waters, sandy beaches and green plants.

So, what’s the bottom line? First, the discovery is extremely exciting. The existence of a nearby planet in the habitable zone will perhaps increase the interest in efforts like Project Starshot, which aims to send microprobes (instruments that apply a stable and wellfocused beam of charged particles -electrons or ions- to a sample) to Proxima Centauri. On the other hand, Proxima b is unlikely to be a haven for people trying to escape the ecological issues of Earth, so we should not view this discovery as a way to ignore our own ecosystem.

Adapted from: < http://edition.cnn.com/2016/08/24/opinions/nearbyplanet-opinion-lincoln/> Access Oct. 2016.

Glossário:

claim: afirmar; dwarf: anão; dim: opaco; give off: emitir;

lizard: lagarto; bask: aquecer-se; belief: crença; wind:

vento; undersurface: camada inferior; lush: viçoso;

bottom line: aspecto fundamental; aim: visar/ter por

objetivo; sample: amostra; haven: refúgio.

Read the text again and answer question.

Which sentence below (adapted from the text)

expresses an advice concerning the conservation of Planet

Earth?