Questões de Vestibular Sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 5.992 questões

https://www.consumerhealthdigest.com/health-awareness/national-depression-screening-day.html acessado em: 05 set. 2017.

https://www.consumerhealthdigest.com/health-awareness/national-depression-screening-day.html acessado em: 05 set. 2017.

De acordo com as informações apresentadas no TEXTO 04, é possível depreender que:

I. Uma a cada cinco pessoas poderá sofrer de depressão.

II. Se a doença não for tratada pode levar à dificuldade de concentração.

III. A depressão é uma das doenças mentais mais comuns entre os jovens australianos.

Está(ão) correta(s) :

A depressão é um problema de saúde pública mundial. Ela se distingue da tristeza pela duração de seus sinais e pelo contexto em que ocorre. Trata-se de uma experiência cotidiana associada a várias sensações de sofrimento psíquico e físico. Leia o TEXTO e responda

Depression in Developing Countries

The National Institute of Mental Health defines depression as a serious but common illness characterized by prolonged periods of sadness. According to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a diagnosis for major depressive disorder requires either symptoms of a depressed mood or loss of interest and pleasure, along with other symptoms such as changes in weight, fatigue or feelings of suicidal thoughts. We can better understand the global impact of depression by measuring it in terms of disability. When analyzed by the disruption and dysfunction it causes in peoples’ lives, depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide. Fortunately, today, many therapies for depression are highly effective.

Disponível em: https://yaleglobalhealthreview.com/2015/05/16/depression-in-developing countries/ . Acessado em: 08 set. 2017. Adaptado.

Na frase “We can better understand the global impact of depression by measuring it in terms of disability”, o pronome

it, em destaque, refere-se:

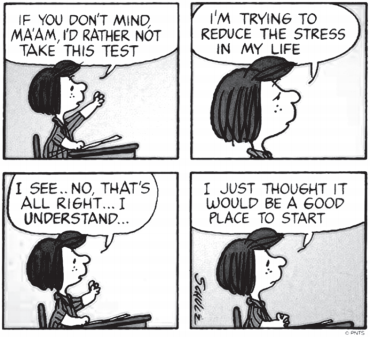

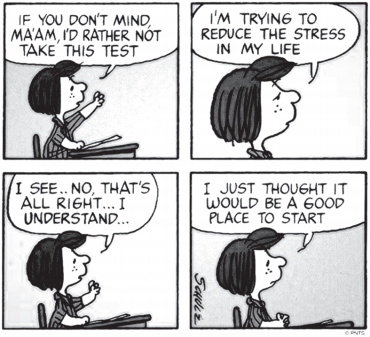

Disponível em: https://i.pinimg.com/736x/52/44/12/5244127bd1ca02b0bd30a8f8db96875a--peanuts-cartoon-peanuts-snoopy.jpg Acesso em: 30 de ago. 2017.

De acordo com o TEXTO, na frase “I’m trying to reduce the stress in my life ”, a palavra reduce só NÃO é sinônimo

de:

Disponível em: https://i.pinimg.com/736x/52/44/12/5244127bd1ca02b0bd30a8f8db96875a--peanuts-cartoon-peanuts-snoopy.jpg Acesso em: 30 de ago. 2017.

Pelo contexto, é possível compreender que:

Nathalie, the swimmer who lost a leg

Nathalie du Toit, the South African swimmer, was only seventeen when she lost her leg in a road accident. She was going to a training session at the swimming pool on her motorbike when a car hit her. Her leg had to be amputated at the knee. At the time she was one of South Africa’s most promising young swimmers. Everybody thought that she would never be able to swim competitively again.

But Nathalie was determined to carry on. She went back into the pool only three months after the accident. And just one year later, at the Commonwalth Games in Manchester, she swam 800 meters in 9 minutes 11:38 seconds and qualified for the final – but not for disabled swimmers, for able-bodied ones! Althought she didn’t win a medal, she still made history.

‘I remember how thrilled I was the first time that I swam after recovering from the operation – it felt like my leg was there. It still does,’ says Nathalie. The water is the gift that gives me back my leg. I’m still the same person I was before the accident. I believe everything happens in life for a reason. You cant go back and change anything. Swimming was my life and still is. My dream is to swim faster than I did before the accident.’

Oxeden, C; KOENIG, C. New English File. Intermediate Student’s Book. OXFORD University Press. (3c-47).

Nathalie, the swimmer who lost a leg

Nathalie du Toit, the South African swimmer, was only seventeen when she lost her leg in a road accident. She was going to a training session at the swimming pool on her motorbike when a car hit her. Her leg had to be amputated at the knee. At the time she was one of South Africa’s most promising young swimmers. Everybody thought that she would never be able to swim competitively again.

But Nathalie was determined to carry on. She went back into the pool only three months after the accident. And just one year later, at the Commonwalth Games in Manchester, she swam 800 meters in 9 minutes 11:38 seconds and qualified for the final – but not for disabled swimmers, for able-bodied ones! Althought she didn’t win a medal, she still made history.

‘I remember how thrilled I was the first time that I swam after recovering from the operation – it felt like my leg was there. It still does,’ says Nathalie. The water is the gift that gives me back my leg. I’m still the same person I was before the accident. I believe everything happens in life for a reason. You cant go back and change anything. Swimming was my life and still is. My dream is to swim faster than I did before the accident.’

Oxeden, C; KOENIG, C. New English File. Intermediate Student’s Book. OXFORD University Press. (3c-47).

Nathalie, the swimmer who lost a leg

Nathalie du Toit, the South African swimmer, was only seventeen when she lost her leg in a road accident. She was going to a training session at the swimming pool on her motorbike when a car hit her. Her leg had to be amputated at the knee. At the time she was one of South Africa’s most promising young swimmers. Everybody thought that she would never be able to swim competitively again.

But Nathalie was determined to carry on. She went back into the pool only three months after the accident. And just one year later, at the Commonwalth Games in Manchester, she swam 800 meters in 9 minutes 11:38 seconds and qualified for the final – but not for disabled swimmers, for able-bodied ones! Althought she didn’t win a medal, she still made history.

‘I remember how thrilled I was the first time that I swam after recovering from the operation – it felt like my leg was there. It still does,’ says Nathalie. The water is the gift that gives me back my leg. I’m still the same person I was before the accident. I believe everything happens in life for a reason. You cant go back and change anything. Swimming was my life and still is. My dream is to swim faster than I did before the accident.’

Oxeden, C; KOENIG, C. New English File. Intermediate Student’s Book. OXFORD University Press. (3c-47).

Nathalie, the swimmer who lost a leg

Nathalie du Toit, the South African swimmer, was only seventeen when she lost her leg in a road accident. She was going to a training session at the swimming pool on her motorbike when a car hit her. Her leg had to be amputated at the knee. At the time she was one of South Africa’s most promising young swimmers. Everybody thought that she would never be able to swim competitively again.

But Nathalie was determined to carry on. She went back into the pool only three months after the accident. And just one year later, at the Commonwalth Games in Manchester, she swam 800 meters in 9 minutes 11:38 seconds and qualified for the final – but not for disabled swimmers, for able-bodied ones! Althought she didn’t win a medal, she still made history.

‘I remember how thrilled I was the first time that I swam after recovering from the operation – it felt like my leg was there. It still does,’ says Nathalie. The water is the gift that gives me back my leg. I’m still the same person I was before the accident. I believe everything happens in life for a reason. You cant go back and change anything. Swimming was my life and still is. My dream is to swim faster than I did before the accident.’

Oxeden, C; KOENIG, C. New English File. Intermediate Student’s Book. OXFORD University Press. (3c-47).

Analise as assertivas a seguir e marque a alternativa CORRETA.

I - A poluição do ar, da água e do solo ocorre separadamente. Por isso, os ecossistemas não são inteiramente impactados.

II - A maioria das fontes de poluição resulta da atividade humana.

III - Reduzir a poluição em uma área de um ecossistema também pode ajudar a proteger outra parte do ecossistema.

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder às questões

Prescriptions for fighting epidemics

Epidemics have plagued humanity since the dawn of

settled life. Yet, success in conquering them remains patchy.

Experts predict that a global one that could kill more than 300

million people would come round in the next 20 to 40 years.

What pathogen would cause it is anybody’s guess. Chances

are that it will be a virus that lurks in birds or mammals, or

one that that has not yet hatched. The scariest are both highly

lethal and spread easily among humans. Thankfully, bugs that

excel at the first tend to be weak at the other. But mutations

– ordinary business for germs – can change that in a blink.

Moreover, when humans get too close to beasts, either

wild or packed in farms, an animal disease can become a

human one.

A front-runner for global pandemics is the seasonal

influenza virus, which mutates so much that a vaccine must

be custom-made every year. The Spanish flu pandemic of

1918, which killed 50 million to 100 million people, was a

potent version of the “swine flu” that emerged in 2009. The

H5N1 “avian flu” strain, deadly in 60% of cases, came about

in the 1990s when a virus that sickened birds made the jump

to a human. Ebola, HIV and Zika took a similar route.

(www.economist.com, 08.02.2018. Adaptado.)