Questões de Vestibular CEDERJ 2014 para Vestibular

Foram encontradas 40 questões

https://www .google.com.br/search?q=escambo+indios+e+portugueses&esp. Acesso em: 05 out.2014.

Prática recorrente nos primeiros séculos da

colonização do Brasil, o escambo consistia na troca ou

permuta de mercadorias, ou mesmo na troca de

mercadorias por trabalho. Assinale a alternativa que

melhor caracteriza essa relação no contexto colonial.

http://www.google.com.br/search?q=bakunin. Acesso em: 06 out. 2014.

Considerado um dos maiores intelectuais do anarquismo, o pensador russo Bakunin, nascido em 1814, defendia que a luta contra o capitalismo era indissociável da luta contra o Estado capitalista.

Sobre o anarquismo, é correta a seguinte afirmação:

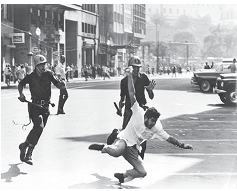

https://www.google.com.br/search?q=imagem+capoeira. Acesso em: 06 out. 2014.

Assinale a alternativa que melhor identifica a

capoeira no Rio de Janeiro do século XIX.

http://www.dw.de/1947- %C3%A9-anunciado-o-plano-marshall/a-568633.Acesso em: 07 out. 2014.

Em 1947, foi colocado em ação o chamado plano

Marshall, nome do então secretário de estado do governo

norte-americano George Marshall. Assinale a alternativa

que melhor explica o objetivo desse plano norte-americano.

https://www.google.com.br/search?q=ditadura+militar+no+brasil.Acesso em: 09 out. 2014.

Segundo o historiador Carlos Fico, “a abordagem propriamente histórica da ditadura militar é recente. Poderíamos dizer que se trata de uma espécie de movimento de incorporação, pelos historiadores, de temáticas outrora teorizadas quase exclusivamente por cientistas políticos e sociólogos e narradas pelos próprios partícipes" (FICO, Carlos. “Versões e controvérsias sobre 1964 e a ditadura militar". http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbh/v24n47/ a03v2447.pdf). Acesso em: 09 out. 2014.

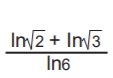

Apesar das distintas interpretações, os historiadores e demais cientistas sociais são unânimes em afirmar que a ditatura militar

é igual a

é igual a Assinale a sentença correta:

H3C-(CH2 )2 -CH(CH3 )-CH(C2H5 )-CH=C(C3 H7 )2

Assinale a alternativa que apresenta uma afirmação correta sobre esse composto.

CS2(l) + 3O2(g) → CO2(g) + 2SO2(g)

2SO3(g)

2SO2(g) + O2(g)

2SO2(g) + O2(g)Assinale a alternativa que apresenta, para a reação dada, a expressão da constante de equilíbrio em termos de pressão parcial:

Alice Munro’s road to Nobel literature prize was not easy

Nobel literature prize winner Alice Munro.

Alice Munro has been awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize in literature, thus becoming its 13th female recipient. It’s a thrilling honour for a major writer: Munro has long been recognised in North America and the UK, but the Nobel will draw international attention, not only to women’s writing and Canadian writing, but to the short story, Munro’s chosen literary genre and one often neglected.

The road to the Nobel wasn’t an easy one for Munro. She found herself referred to as “some housewife”, and was told that her subject matter, being too “domestic”, was boring. A male writer told her she wrote good stories, but he wouldn’t want to sleep with her. “Nobody invited him,” said Munro. Maybe as a consequence of this initial reaction towards her, when writers occur in Munro stories, they are pretentious, or exploitative of others; or they’re being asked by their relatives why they aren’t famous, or – worse, if female – why they aren’t better-looking.

The chances that a literary star would emerge from her time and place would once have been zero. Munro was born in 1931, and thus experienced the Depression as a child and the Second World War as a teenager. This was in south-western Ontario, Canada, a region that also produced equally talented writers and poets such as Robertson Davies, Graeme Gibson, James Reaney, and Marian Engel. It’s this small-town setting that features most often in her stories – the snobberies, the eccentrics, and the jeering at ambitions, especially artistic ones.

Shame is a common driving force for Munro’s characters just as perfectionism in the writing and courage in her profession have been driving forces for her.

As in much else, Munro is essentially Canadian. Faced with the Nobel, she will be modest, she won’t get a swelled head. The rest of us, on this magnificent occasion, will just have to do that for her.

Alice Munro’s road to Nobel literature prize was not easy

Nobel literature prize winner Alice Munro.

Alice Munro has been awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize in literature, thus becoming its 13th female recipient. It’s a thrilling honour for a major writer: Munro has long been recognised in North America and the UK, but the Nobel will draw international attention, not only to women’s writing and Canadian writing, but to the short story, Munro’s chosen literary genre and one often neglected.

The road to the Nobel wasn’t an easy one for Munro. She found herself referred to as “some housewife”, and was told that her subject matter, being too “domestic”, was boring. A male writer told her she wrote good stories, but he wouldn’t want to sleep with her. “Nobody invited him,” said Munro. Maybe as a consequence of this initial reaction towards her, when writers occur in Munro stories, they are pretentious, or exploitative of others; or they’re being asked by their relatives why they aren’t famous, or – worse, if female – why they aren’t better-looking.

The chances that a literary star would emerge from her time and place would once have been zero. Munro was born in 1931, and thus experienced the Depression as a child and the Second World War as a teenager. This was in south-western Ontario, Canada, a region that also produced equally talented writers and poets such as Robertson Davies, Graeme Gibson, James Reaney, and Marian Engel. It’s this small-town setting that features most often in her stories – the snobberies, the eccentrics, and the jeering at ambitions, especially artistic ones.

Shame is a common driving force for Munro’s characters just as perfectionism in the writing and courage in her profession have been driving forces for her.

As in much else, Munro is essentially Canadian. Faced with the Nobel, she will be modest, she won’t get a swelled head. The rest of us, on this magnificent occasion, will just have to do that for her.

Alice Munro’s road to Nobel literature prize was not easy

Nobel literature prize winner Alice Munro.

Alice Munro has been awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize in literature, thus becoming its 13th female recipient. It’s a thrilling honour for a major writer: Munro has long been recognised in North America and the UK, but the Nobel will draw international attention, not only to women’s writing and Canadian writing, but to the short story, Munro’s chosen literary genre and one often neglected.

The road to the Nobel wasn’t an easy one for Munro. She found herself referred to as “some housewife”, and was told that her subject matter, being too “domestic”, was boring. A male writer told her she wrote good stories, but he wouldn’t want to sleep with her. “Nobody invited him,” said Munro. Maybe as a consequence of this initial reaction towards her, when writers occur in Munro stories, they are pretentious, or exploitative of others; or they’re being asked by their relatives why they aren’t famous, or – worse, if female – why they aren’t better-looking.

The chances that a literary star would emerge from her time and place would once have been zero. Munro was born in 1931, and thus experienced the Depression as a child and the Second World War as a teenager. This was in south-western Ontario, Canada, a region that also produced equally talented writers and poets such as Robertson Davies, Graeme Gibson, James Reaney, and Marian Engel. It’s this small-town setting that features most often in her stories – the snobberies, the eccentrics, and the jeering at ambitions, especially artistic ones.

Shame is a common driving force for Munro’s characters just as perfectionism in the writing and courage in her profession have been driving forces for her.

As in much else, Munro is essentially Canadian. Faced with the Nobel, she will be modest, she won’t get a swelled head. The rest of us, on this magnificent occasion, will just have to do that for her.

Alice Munro’s road to Nobel literature prize was not easy

Nobel literature prize winner Alice Munro.

Alice Munro has been awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize in literature, thus becoming its 13th female recipient. It’s a thrilling honour for a major writer: Munro has long been recognised in North America and the UK, but the Nobel will draw international attention, not only to women’s writing and Canadian writing, but to the short story, Munro’s chosen literary genre and one often neglected.

The road to the Nobel wasn’t an easy one for Munro. She found herself referred to as “some housewife”, and was told that her subject matter, being too “domestic”, was boring. A male writer told her she wrote good stories, but he wouldn’t want to sleep with her. “Nobody invited him,” said Munro. Maybe as a consequence of this initial reaction towards her, when writers occur in Munro stories, they are pretentious, or exploitative of others; or they’re being asked by their relatives why they aren’t famous, or – worse, if female – why they aren’t better-looking.

The chances that a literary star would emerge from her time and place would once have been zero. Munro was born in 1931, and thus experienced the Depression as a child and the Second World War as a teenager. This was in south-western Ontario, Canada, a region that also produced equally talented writers and poets such as Robertson Davies, Graeme Gibson, James Reaney, and Marian Engel. It’s this small-town setting that features most often in her stories – the snobberies, the eccentrics, and the jeering at ambitions, especially artistic ones.

Shame is a common driving force for Munro’s characters just as perfectionism in the writing and courage in her profession have been driving forces for her.

As in much else, Munro is essentially Canadian. Faced with the Nobel, she will be modest, she won’t get a swelled head. The rest of us, on this magnificent occasion, will just have to do that for her.

In the third paragraph, in the sentence “This was in south-western Ontario", the pronoun “this" refers to

Alice Munro’s road to Nobel literature prize was not easy

Nobel literature prize winner Alice Munro.

Alice Munro has been awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize in literature, thus becoming its 13th female recipient. It’s a thrilling honour for a major writer: Munro has long been recognised in North America and the UK, but the Nobel will draw international attention, not only to women’s writing and Canadian writing, but to the short story, Munro’s chosen literary genre and one often neglected.

The road to the Nobel wasn’t an easy one for Munro. She found herself referred to as “some housewife”, and was told that her subject matter, being too “domestic”, was boring. A male writer told her she wrote good stories, but he wouldn’t want to sleep with her. “Nobody invited him,” said Munro. Maybe as a consequence of this initial reaction towards her, when writers occur in Munro stories, they are pretentious, or exploitative of others; or they’re being asked by their relatives why they aren’t famous, or – worse, if female – why they aren’t better-looking.

The chances that a literary star would emerge from her time and place would once have been zero. Munro was born in 1931, and thus experienced the Depression as a child and the Second World War as a teenager. This was in south-western Ontario, Canada, a region that also produced equally talented writers and poets such as Robertson Davies, Graeme Gibson, James Reaney, and Marian Engel. It’s this small-town setting that features most often in her stories – the snobberies, the eccentrics, and the jeering at ambitions, especially artistic ones.

Shame is a common driving force for Munro’s characters just as perfectionism in the writing and courage in her profession have been driving forces for her.

As in much else, Munro is essentially Canadian. Faced with the Nobel, she will be modest, she won’t get a swelled head. The rest of us, on this magnificent occasion, will just have to do that for her.

Besides Alice Munro's talent and courage, what other quality of this Nobel Prize winner is emphasized in the article?