Questões de Concurso

Sobre interpretação de texto | reading comprehension em inglês

Foram encontradas 9.474 questões

One of the things Jaime appreciates about Accela is that “they believe in their product so much, you don’t have to sign on for a year. With Accela, we didn’t feel they were trying to get the most money they could from the agency. We felt they truly were a company that wanted to work with us and were understanding of all the different requirements we had.”

One of the things Jaime appreciates about Accela is that “they believe in their product so much, you don’t have to sign on for a year. With Accela, we didn’t feel they were trying to get the most money they could from the agency. We felt they truly were a company that wanted to work with us and were understanding of all the different requirements we had.”

De acordo com o texto,

One of the things Jaime appreciates about Accela is that “they believe in their product so much, you don’t have to sign on for a year. With Accela, we didn’t feel they were trying to get the most money they could from the agency. We felt they truly were a company that wanted to work with us and were understanding of all the different requirements we had.”

Text VII

The term ‘assessment literacy’ has been coined in recent years to denote what teachers need to know about assessment. Traditionally, it was regarded as the ability to select, design and evaluate tests and assessment procedures, as well as to score and grade them on the basis of theoretical knowledge. More recent approaches embrace a broader understanding of the concept when taking account of the implications of assessment for teaching. […] Knowing and understanding the key principles of sound assessment and translating those into quality information about students’ achievements and effective instruction are considered essential.

(BERGER, A. Creating Language ‐ Assessment Literacy: A Model for Teacher Education. In: HÜTTNER, J.; MEHLMAUER‐LARCHER, B.; REICH, S. (eds.) Theory and Practice in EFL Teaching Education: Bridging the Gap. Multilingual Matters, 2012. pp.57‐82.)

Match the descriptions that apply to summative, formative or diagnostic assessment. Note that more than one description can apply to one type of assessment.

I. It can help the teacher to identify students' current knowledge of a subject.

II. It provides feedback and information during the instructional process.

III. It takes place when learning has been completed and provides information and feedback that sum up the teaching and learning process.

IV. It is typically given to students at the end of a set point.

Text VII

The term ‘assessment literacy’ has been coined in recent years to denote what teachers need to know about assessment. Traditionally, it was regarded as the ability to select, design and evaluate tests and assessment procedures, as well as to score and grade them on the basis of theoretical knowledge. More recent approaches embrace a broader understanding of the concept when taking account of the implications of assessment for teaching. […] Knowing and understanding the key principles of sound assessment and translating those into quality information about students’ achievements and effective instruction are considered essential.

(BERGER, A. Creating Language ‐ Assessment Literacy: A Model for Teacher Education. In: HÜTTNER, J.; MEHLMAUER‐LARCHER, B.; REICH, S. (eds.) Theory and Practice in EFL Teaching Education: Bridging the Gap. Multilingual Matters, 2012. pp.57‐82.)

Text VI.

Critical Discourse Analysis

We have seen that among many other resources that define the power base of a group or institution, access to or control over public discourse and communication is an important "symbolic" resource, as is the case for knowledge and information (van Dijk 1996). Most people have active control only over everyday talk with family members, friends, or colleagues, and passive control over, e.g. media usage. In many situations, ordinary people are more or less passive targets of text and talk, e.g. of their bosses or teachers, or of the authorities, such as police officers, judges, welfare bureaucrats, or tax inspectors, who may simply tell them what (not) to believe or what to do.

On the other hand, members of more powerful social groups and institutions, and especially their leaders (the elites), have more or less exclusive access to, and control over, one or more types of public discourse. Thus, professors control scholarly discourse, teachers educational discourse, journalists media discourse, lawyers legal discourse, and politicians policy and other public political discourse. Those who have more control over more ‒ and more influential ‒ discourse (and more properties) are by that definition also more powerful.

These notions of discourse access and control are very general, and it is one of the tasks of CDA to spell out these forms of power. Thus, if discourse is defined in terms of complex communicative events, access and control may be defined both for the context and for the structures of text and talk themselves.

(van DIJK, T. A. Critical Discourse Analysis. In: SCHIFFRIN, D.; TANNEN, D.; HAMILTON, H. (eds.). The Handbook of Discourse Analysis, Wiley‐Blackwell, 2003. pp. 352‐371.)

Identify the illocutionary force of the professor's utterance below:

Professor to Undergraduates during a class at the university: “How's that paper doing? It's due on Monday.”

(Adapted from: http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~haroldfs/dravling/illocutionary.html. Accessed on October 24, 2014.)

Text VI.

Critical Discourse Analysis

We have seen that among many other resources that define the power base of a group or institution, access to or control over public discourse and communication is an important "symbolic" resource, as is the case for knowledge and information (van Dijk 1996). Most people have active control only over everyday talk with family members, friends, or colleagues, and passive control over, e.g. media usage. In many situations, ordinary people are more or less passive targets of text and talk, e.g. of their bosses or teachers, or of the authorities, such as police officers, judges, welfare bureaucrats, or tax inspectors, who may simply tell them what (not) to believe or what to do.

On the other hand, members of more powerful social groups and institutions, and especially their leaders (the elites), have more or less exclusive access to, and control over, one or more types of public discourse. Thus, professors control scholarly discourse, teachers educational discourse, journalists media discourse, lawyers legal discourse, and politicians policy and other public political discourse. Those who have more control over more ‒ and more influential ‒ discourse (and more properties) are by that definition also more powerful.

These notions of discourse access and control are very general, and it is one of the tasks of CDA to spell out these forms of power. Thus, if discourse is defined in terms of complex communicative events, access and control may be defined both for the context and for the structures of text and talk themselves.

(van DIJK, T. A. Critical Discourse Analysis. In: SCHIFFRIN, D.; TANNEN, D.; HAMILTON, H. (eds.). The Handbook of Discourse Analysis, Wiley‐Blackwell, 2003. pp. 352‐371.)

Text V

[…] Language teachers can ill afford to ignore the sociocultural reality that influences identity formation in the classroom, nor can they afford to separate the linguistic needs of learners from their social needs. In other words, language teachers cannot hope to fully satisfy their pedagogic obligations without at the same time satisfying their social obligations. They will be able to reconcile these seemingly competing forces if they “achieve a deepening awareness both of the sociocultural reality that shapes their lives and of their capacity to transform that reality” (van Manen, 1977, p. 222). Such a deepening awareness has a built‐in quality that transforms the life of the person who adopts it. Studies by Clandinin, Davies, Hogan, and Kennard (1993) attest to this self‐transforming phenomenon:

As we worked together we talked about ways of seeing new possibility in our practices as teachers, as teacher educators, and with children in our classroom. As we saw possibilities in our professional lives we also came to see new possibilities in our personal lives. (p. 209)

(KUMARAVADIVELU, B. Toward a Post‐method Pedagogy. In: Tesol Quarterly, vol.35, No. 4, Winter, 2001, p.544.)

Text V

[…] Language teachers can ill afford to ignore the sociocultural reality that influences identity formation in the classroom, nor can they afford to separate the linguistic needs of learners from their social needs. In other words, language teachers cannot hope to fully satisfy their pedagogic obligations without at the same time satisfying their social obligations. They will be able to reconcile these seemingly competing forces if they “achieve a deepening awareness both of the sociocultural reality that shapes their lives and of their capacity to transform that reality” (van Manen, 1977, p. 222). Such a deepening awareness has a built‐in quality that transforms the life of the person who adopts it. Studies by Clandinin, Davies, Hogan, and Kennard (1993) attest to this self‐transforming phenomenon:

As we worked together we talked about ways of seeing new possibility in our practices as teachers, as teacher educators, and with children in our classroom. As we saw possibilities in our professional lives we also came to see new possibilities in our personal lives. (p. 209)

(KUMARAVADIVELU, B. Toward a Post‐method Pedagogy. In: Tesol Quarterly, vol.35, No. 4, Winter, 2001, p.544.)

Text IV

Identity and Interaction: a sociocultural linguistic approach

Different research traditions within sociocultural linguistics have particular strengths in analyzing the varied dimensions of identity outlined in this article. The method of analysis selected by the researcher makes salient which aspect of identity comes into view, and such 'partial accounts' contribute to the broader understanding of identity that we advocate here. Although these lines of research have often remained separate from one another, the combination of their diverse theoretical and methodological strengths ‒ including the microanalysis of conversation, the macroanalysis of ideological processes, the quantitative and qualitative analysis of linguistic structures, and the ethnographic focus on local cultural practices and social groupings ‒ calls attention to the fact that identity in all its complexity can never be contained within a single analysis. For this reason, it is necessary to conceive of sociocultural linguistics broadly and inclusively. The five principles proposed here ‒ Emergence, Positionality, Indexicality, Relationality, and Partialness ‒ represent the varied ways in which different kinds of scholars currently approach the question of identity. Even researchers whose primary goals lie elsewhere can contribute to this project by providing sophisticated conceptualizations of how human dynamics unfold in discourse, along with rigorous analytic tools for discovering how such processes work. While identity has been a widely circulating notion in sociocultural linguistic research for some time, few scholars have explicitly theorized the concept. The present article offers one way of understanding this body of work by anchoring identity in interaction. By positing, in keeping with recent scholarship, that identity is emergent in discourse and does not precede it, we are able to locate identity as an intersubjectively achieved social and cultural phenomenon. This discursive approach further allows us to incorporate within identity not only the broad sociological categories most commonly associated with the concept, but also more local positionings, both ethnographic and interactional. The linguistic resources that indexically produce identity at all these levels are therefore necessarily broad and flexible, including labels, implicatures, stances, styles, and entire languages and varieties. Because these tools are put to use in interaction, the process of identity construction does not reside within the individual but in intersubjective relations of sameness and difference, realness and fakeness, power and disempowerment. Finally, by theorizing agency as a broader phenomenon than simply individualistic and deliberate action, we are able to call attention to the myriad ways that identity comes into being, from habitual practice to interactional negotiation to representations and ideologies.

It is no overstatement to assert that the age of identity is upon us, not only in sociocultural linguistics but also in the human and social sciences more generally. Scholars of language use are particularly well equipped to provide an empirically viable account of the complexities of identity as a social, cultural, and ‒ most fundamentally ‒ interactional phenomenon. The recognition of the loose coalition of approaches that we call sociocultural linguistics is a necessary step in advancing this goal, for it is only by understanding our diverse theories and methods as complementary, not competing, that we can meaningfully interpret this crucial dimension of contemporary social life.

(BUCHOLTZ, M.; HALL, K. Identity and interaction: a sociocultural approach. In: Discourse Studies, vol 7 (4‐5). London: SAGE, 2005. pp. 585‐614.)

Text IV

Identity and Interaction: a sociocultural linguistic approach

Different research traditions within sociocultural linguistics have particular strengths in analyzing the varied dimensions of identity outlined in this article. The method of analysis selected by the researcher makes salient which aspect of identity comes into view, and such 'partial accounts' contribute to the broader understanding of identity that we advocate here. Although these lines of research have often remained separate from one another, the combination of their diverse theoretical and methodological strengths ‒ including the microanalysis of conversation, the macroanalysis of ideological processes, the quantitative and qualitative analysis of linguistic structures, and the ethnographic focus on local cultural practices and social groupings ‒ calls attention to the fact that identity in all its complexity can never be contained within a single analysis. For this reason, it is necessary to conceive of sociocultural linguistics broadly and inclusively. The five principles proposed here ‒ Emergence, Positionality, Indexicality, Relationality, and Partialness ‒ represent the varied ways in which different kinds of scholars currently approach the question of identity. Even researchers whose primary goals lie elsewhere can contribute to this project by providing sophisticated conceptualizations of how human dynamics unfold in discourse, along with rigorous analytic tools for discovering how such processes work. While identity has been a widely circulating notion in sociocultural linguistic research for some time, few scholars have explicitly theorized the concept. The present article offers one way of understanding this body of work by anchoring identity in interaction. By positing, in keeping with recent scholarship, that identity is emergent in discourse and does not precede it, we are able to locate identity as an intersubjectively achieved social and cultural phenomenon. This discursive approach further allows us to incorporate within identity not only the broad sociological categories most commonly associated with the concept, but also more local positionings, both ethnographic and interactional. The linguistic resources that indexically produce identity at all these levels are therefore necessarily broad and flexible, including labels, implicatures, stances, styles, and entire languages and varieties. Because these tools are put to use in interaction, the process of identity construction does not reside within the individual but in intersubjective relations of sameness and difference, realness and fakeness, power and disempowerment. Finally, by theorizing agency as a broader phenomenon than simply individualistic and deliberate action, we are able to call attention to the myriad ways that identity comes into being, from habitual practice to interactional negotiation to representations and ideologies.

It is no overstatement to assert that the age of identity is upon us, not only in sociocultural linguistics but also in the human and social sciences more generally. Scholars of language use are particularly well equipped to provide an empirically viable account of the complexities of identity as a social, cultural, and ‒ most fundamentally ‒ interactional phenomenon. The recognition of the loose coalition of approaches that we call sociocultural linguistics is a necessary step in advancing this goal, for it is only by understanding our diverse theories and methods as complementary, not competing, that we can meaningfully interpret this crucial dimension of contemporary social life.

(BUCHOLTZ, M.; HALL, K. Identity and interaction: a sociocultural approach. In: Discourse Studies, vol 7 (4‐5). London: SAGE, 2005. pp. 585‐614.)

Choose the best ending for the following sentence, according to the text: In order to understand the construction of identity, __________________________________.

Text II

Reading Comprehension Instruction

There are widespread and erroneous perceptions that children must know all of the words before they can comprehend a text and that they must comprehend it at the literal level before advancing to comprehension at the inferential level.

Recognizing some words is clearly necessary and central to reading. It is important for children to acquire a set of strategies for figuring out the meanings of words and apply these strategies so that words are recognized automatically. Four groups of strategies exist: (1) common graphophonic patterns (e.g., at in cat, hat, bat), (2) high‐frequency or common words used in sentences (e.g., the, a, or), (3) word building (e.g., morphemes, as play in plays, played, playing, playful), and (4) contextual supports gathered through the meanings of sentences, texts, and illustrations. These word recognition strategies are taught as children are engaged in reading and are considered effective in fluency instruction.

Vocabulary and reading comprehension growth occurs side by side even for beginning readers. They each require explicit instruction and lots of reading of stories including repeated readings to teach phonics, to develop sight vocabulary, and to teach children how to decode words; guided retelling using questions that prompt children to name the characters, identify the setting (place and time), speak to the problem, tell what happened, and how the story ended; repeated checking for information; and drawing conclusions. Teaching strategies to children early, explicitly, and sequentially are three key characteristics of effective vocabulary and reading comprehension instruction.

For those who are learning English as second or foreign language, take advantage of their first language knowledge to identify cognate pairs, which are words with similar spellings, pronunciations, and meanings in English. To identify the degree of overlap between the two languages is a strategy that has been demonstrated to be effective for Spanish‐ literate children: learn the words for basic objects (e.g., dog, cat, house, car) that English‐only children already know; review and practice passages and stories through read‐alouds in order to accelerate the rate at which words can be identified and read; and engage in basic reading skills including spelling.

(PHILLIPS, L.M, NORRIS, S. P. & VAVRA, K.L. Reading Comprehension Instruction (pp. 1‐10). Faculty of Education, University of Alberta. Posted online on 2007‐11‐20 in: http://www.literacyencyclopedia.ca)

Decide whether the following statements are true or false, according to the text above and then choose the right alternative:

I. Comprehension of a text involves understanding of all its words.

II. Children learn how to read naturally, without the support of reading strategies instruction.

III. The development of the lexical system of the language and reading comprehension abilities takes place simultaneously.

IV. The knowledge of transparent words is not beneficial for learners of English as a SL or a FL.

Text I

Critical Literacy and Foreign Language Education

Understanding the basic principles of Critical Literacy is vital for establishing a viable relationship between EFL teaching and the general (critical) education of the individual. Critical literacy supporters conceive literacy in broader socio‐cultural and political terms. Critical literacy is mainly derived from post‐structuralism, critical social theory and critical pedagogy. From post‐structuralism, critical literacy has borrowed its methods of critique and the understanding of texts as ideological constructions embedded within discursive systems. Based on critical social theory, critical literacy sees texts as continually subjected to methods of social critique. Finally, because of the influence of critical pedagogy, critical literacy practices need to draw on social justice, freedom, and equity as central concerns. As I am discussing critical literacy and language education in Brazilian contexts, I will highlight the contributions of Paulo Freire's Critical Pedagogy. Freire's contributions to the conceptualization of critical literacy are fundamental, as critical literacy essentially determines a different attitude towards reading. Reading the word is not enough. As stated in Freire's work, reading the word and reading the world should be intrinsically related, as any text is embedded in comprehensive contexts of social, historical, and power relations that generate it. Moreover, the critical reading of the word within the world, and vice‐versa, is a tool for social transformation. Consequently, critical pedagogies to literacy centralize issues of social justice and emancipation. How does critical pedagogy enlighten the roles to be played by EFL teaching in the education, for example, about race relations?

A major concern of Freire's critical pedagogy as well as for other educators committed to critical forms of education is the development of "critical consciousness." Through critical consciousness, students should come to recognize and feel disposed to remake their own identities and sociopolitical realities through their own meaning‐making processes and through their actions in the world. Ultimately, critical literacy is an instrument of power and provides a possibility of transforming the society if the empowered individual wants to.

Considering the status of English as a lingua franca, materials, especially those de‐signed by publishers in the US and UK, are used for organizing lessons around topics that can be included in classroom activities without causing discomfort, so that the same textbook series can be sold to different parts of the world. Some publishers even have lists of banned topics or rely informally on the acronym PARSNIP (politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, isms, and pork) as a rule of thumb.

The convention of avoidance, then, is related to problems that tend to be purposefully neglected and are those that customarily are the most meaningful issues in real world students' lives. The avoided topics are also close to the ones suggested by OCEM as topics that should be present in Brazilian schools to promote critical literacy. Teachers of English, as well as any other teacher, face, in their daily teaching, educational challenges that go beyond the imagined protected spaces of schools and the imagined worlds portrayed in textbooks. What seems to be relevant in students' lives are not necessarily common topics included in EFL textbooks, such as ‘Mr. Smith's weekend' or ‘global warming', although these can be considered valid topics to be discussed in classrooms.

Considering all these challenges, it is necessary to define the role of teacher education in this process. Teachers should be seen as transformative agents and their education should be focused upon this perspective. This encompasses the traditional contents of sociology of education, psychology of education, educational legislation and other subjects. But, the specific weight on ELT needs to entail criticism of current practices and suggestions for creating new ones.

(JORGE, M. Critical literacy, foreign language teaching and the education about race relations in Brazil. In: The Latin Americanist, vol. 56, 4, December 2012, pp. 79‐90. Available in: https://www.academia.edu . Accessed on September 24th, 2014.)

Text I

Critical Literacy and Foreign Language Education

Understanding the basic principles of Critical Literacy is vital for establishing a viable relationship between EFL teaching and the general (critical) education of the individual. Critical literacy supporters conceive literacy in broader socio‐cultural and political terms. Critical literacy is mainly derived from post‐structuralism, critical social theory and critical pedagogy. From post‐structuralism, critical literacy has borrowed its methods of critique and the understanding of texts as ideological constructions embedded within discursive systems. Based on critical social theory, critical literacy sees texts as continually subjected to methods of social critique. Finally, because of the influence of critical pedagogy, critical literacy practices need to draw on social justice, freedom, and equity as central concerns. As I am discussing critical literacy and language education in Brazilian contexts, I will highlight the contributions of Paulo Freire's Critical Pedagogy. Freire's contributions to the conceptualization of critical literacy are fundamental, as critical literacy essentially determines a different attitude towards reading. Reading the word is not enough. As stated in Freire's work, reading the word and reading the world should be intrinsically related, as any text is embedded in comprehensive contexts of social, historical, and power relations that generate it. Moreover, the critical reading of the word within the world, and vice‐versa, is a tool for social transformation. Consequently, critical pedagogies to literacy centralize issues of social justice and emancipation. How does critical pedagogy enlighten the roles to be played by EFL teaching in the education, for example, about race relations?

A major concern of Freire's critical pedagogy as well as for other educators committed to critical forms of education is the development of "critical consciousness." Through critical consciousness, students should come to recognize and feel disposed to remake their own identities and sociopolitical realities through their own meaning‐making processes and through their actions in the world. Ultimately, critical literacy is an instrument of power and provides a possibility of transforming the society if the empowered individual wants to.

Considering the status of English as a lingua franca, materials, especially those de‐signed by publishers in the US and UK, are used for organizing lessons around topics that can be included in classroom activities without causing discomfort, so that the same textbook series can be sold to different parts of the world. Some publishers even have lists of banned topics or rely informally on the acronym PARSNIP (politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, isms, and pork) as a rule of thumb.

The convention of avoidance, then, is related to problems that tend to be purposefully neglected and are those that customarily are the most meaningful issues in real world students' lives. The avoided topics are also close to the ones suggested by OCEM as topics that should be present in Brazilian schools to promote critical literacy. Teachers of English, as well as any other teacher, face, in their daily teaching, educational challenges that go beyond the imagined protected spaces of schools and the imagined worlds portrayed in textbooks. What seems to be relevant in students' lives are not necessarily common topics included in EFL textbooks, such as ‘Mr. Smith's weekend' or ‘global warming', although these can be considered valid topics to be discussed in classrooms.

Considering all these challenges, it is necessary to define the role of teacher education in this process. Teachers should be seen as transformative agents and their education should be focused upon this perspective. This encompasses the traditional contents of sociology of education, psychology of education, educational legislation and other subjects. But, the specific weight on ELT needs to entail criticism of current practices and suggestions for creating new ones.

(JORGE, M. Critical literacy, foreign language teaching and the education about race relations in Brazil. In: The Latin Americanist, vol. 56, 4, December 2012, pp. 79‐90. Available in: https://www.academia.edu . Accessed on September 24th, 2014.)

Text I

Critical Literacy and Foreign Language Education

Understanding the basic principles of Critical Literacy is vital for establishing a viable relationship between EFL teaching and the general (critical) education of the individual. Critical literacy supporters conceive literacy in broader socio‐cultural and political terms. Critical literacy is mainly derived from post‐structuralism, critical social theory and critical pedagogy. From post‐structuralism, critical literacy has borrowed its methods of critique and the understanding of texts as ideological constructions embedded within discursive systems. Based on critical social theory, critical literacy sees texts as continually subjected to methods of social critique. Finally, because of the influence of critical pedagogy, critical literacy practices need to draw on social justice, freedom, and equity as central concerns. As I am discussing critical literacy and language education in Brazilian contexts, I will highlight the contributions of Paulo Freire's Critical Pedagogy. Freire's contributions to the conceptualization of critical literacy are fundamental, as critical literacy essentially determines a different attitude towards reading. Reading the word is not enough. As stated in Freire's work, reading the word and reading the world should be intrinsically related, as any text is embedded in comprehensive contexts of social, historical, and power relations that generate it. Moreover, the critical reading of the word within the world, and vice‐versa, is a tool for social transformation. Consequently, critical pedagogies to literacy centralize issues of social justice and emancipation. How does critical pedagogy enlighten the roles to be played by EFL teaching in the education, for example, about race relations?

A major concern of Freire's critical pedagogy as well as for other educators committed to critical forms of education is the development of "critical consciousness." Through critical consciousness, students should come to recognize and feel disposed to remake their own identities and sociopolitical realities through their own meaning‐making processes and through their actions in the world. Ultimately, critical literacy is an instrument of power and provides a possibility of transforming the society if the empowered individual wants to.

Considering the status of English as a lingua franca, materials, especially those de‐signed by publishers in the US and UK, are used for organizing lessons around topics that can be included in classroom activities without causing discomfort, so that the same textbook series can be sold to different parts of the world. Some publishers even have lists of banned topics or rely informally on the acronym PARSNIP (politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, isms, and pork) as a rule of thumb.

The convention of avoidance, then, is related to problems that tend to be purposefully neglected and are those that customarily are the most meaningful issues in real world students' lives. The avoided topics are also close to the ones suggested by OCEM as topics that should be present in Brazilian schools to promote critical literacy. Teachers of English, as well as any other teacher, face, in their daily teaching, educational challenges that go beyond the imagined protected spaces of schools and the imagined worlds portrayed in textbooks. What seems to be relevant in students' lives are not necessarily common topics included in EFL textbooks, such as ‘Mr. Smith's weekend' or ‘global warming', although these can be considered valid topics to be discussed in classrooms.

Considering all these challenges, it is necessary to define the role of teacher education in this process. Teachers should be seen as transformative agents and their education should be focused upon this perspective. This encompasses the traditional contents of sociology of education, psychology of education, educational legislation and other subjects. But, the specific weight on ELT needs to entail criticism of current practices and suggestions for creating new ones.

(JORGE, M. Critical literacy, foreign language teaching and the education about race relations in Brazil. In: The Latin Americanist, vol. 56, 4, December 2012, pp. 79‐90. Available in: https://www.academia.edu . Accessed on September 24th, 2014.)

Text I

Critical Literacy and Foreign Language Education

Understanding the basic principles of Critical Literacy is vital for establishing a viable relationship between EFL teaching and the general (critical) education of the individual. Critical literacy supporters conceive literacy in broader socio‐cultural and political terms. Critical literacy is mainly derived from post‐structuralism, critical social theory and critical pedagogy. From post‐structuralism, critical literacy has borrowed its methods of critique and the understanding of texts as ideological constructions embedded within discursive systems. Based on critical social theory, critical literacy sees texts as continually subjected to methods of social critique. Finally, because of the influence of critical pedagogy, critical literacy practices need to draw on social justice, freedom, and equity as central concerns. As I am discussing critical literacy and language education in Brazilian contexts, I will highlight the contributions of Paulo Freire's Critical Pedagogy. Freire's contributions to the conceptualization of critical literacy are fundamental, as critical literacy essentially determines a different attitude towards reading. Reading the word is not enough. As stated in Freire's work, reading the word and reading the world should be intrinsically related, as any text is embedded in comprehensive contexts of social, historical, and power relations that generate it. Moreover, the critical reading of the word within the world, and vice‐versa, is a tool for social transformation. Consequently, critical pedagogies to literacy centralize issues of social justice and emancipation. How does critical pedagogy enlighten the roles to be played by EFL teaching in the education, for example, about race relations?

A major concern of Freire's critical pedagogy as well as for other educators committed to critical forms of education is the development of "critical consciousness." Through critical consciousness, students should come to recognize and feel disposed to remake their own identities and sociopolitical realities through their own meaning‐making processes and through their actions in the world. Ultimately, critical literacy is an instrument of power and provides a possibility of transforming the society if the empowered individual wants to.

Considering the status of English as a lingua franca, materials, especially those de‐signed by publishers in the US and UK, are used for organizing lessons around topics that can be included in classroom activities without causing discomfort, so that the same textbook series can be sold to different parts of the world. Some publishers even have lists of banned topics or rely informally on the acronym PARSNIP (politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, isms, and pork) as a rule of thumb.

The convention of avoidance, then, is related to problems that tend to be purposefully neglected and are those that customarily are the most meaningful issues in real world students' lives. The avoided topics are also close to the ones suggested by OCEM as topics that should be present in Brazilian schools to promote critical literacy. Teachers of English, as well as any other teacher, face, in their daily teaching, educational challenges that go beyond the imagined protected spaces of schools and the imagined worlds portrayed in textbooks. What seems to be relevant in students' lives are not necessarily common topics included in EFL textbooks, such as ‘Mr. Smith's weekend' or ‘global warming', although these can be considered valid topics to be discussed in classrooms.

Considering all these challenges, it is necessary to define the role of teacher education in this process. Teachers should be seen as transformative agents and their education should be focused upon this perspective. This encompasses the traditional contents of sociology of education, psychology of education, educational legislation and other subjects. But, the specific weight on ELT needs to entail criticism of current practices and suggestions for creating new ones.

(JORGE, M. Critical literacy, foreign language teaching and the education about race relations in Brazil. In: The Latin Americanist, vol. 56, 4, December 2012, pp. 79‐90. Available in: https://www.academia.edu . Accessed on September 24th, 2014.)

Text I

Critical Literacy and Foreign Language Education

Understanding the basic principles of Critical Literacy is vital for establishing a viable relationship between EFL teaching and the general (critical) education of the individual. Critical literacy supporters conceive literacy in broader socio‐cultural and political terms. Critical literacy is mainly derived from post‐structuralism, critical social theory and critical pedagogy. From post‐structuralism, critical literacy has borrowed its methods of critique and the understanding of texts as ideological constructions embedded within discursive systems. Based on critical social theory, critical literacy sees texts as continually subjected to methods of social critique. Finally, because of the influence of critical pedagogy, critical literacy practices need to draw on social justice, freedom, and equity as central concerns. As I am discussing critical literacy and language education in Brazilian contexts, I will highlight the contributions of Paulo Freire's Critical Pedagogy. Freire's contributions to the conceptualization of critical literacy are fundamental, as critical literacy essentially determines a different attitude towards reading. Reading the word is not enough. As stated in Freire's work, reading the word and reading the world should be intrinsically related, as any text is embedded in comprehensive contexts of social, historical, and power relations that generate it. Moreover, the critical reading of the word within the world, and vice‐versa, is a tool for social transformation. Consequently, critical pedagogies to literacy centralize issues of social justice and emancipation. How does critical pedagogy enlighten the roles to be played by EFL teaching in the education, for example, about race relations?

A major concern of Freire's critical pedagogy as well as for other educators committed to critical forms of education is the development of "critical consciousness." Through critical consciousness, students should come to recognize and feel disposed to remake their own identities and sociopolitical realities through their own meaning‐making processes and through their actions in the world. Ultimately, critical literacy is an instrument of power and provides a possibility of transforming the society if the empowered individual wants to.

Considering the status of English as a lingua franca, materials, especially those de‐signed by publishers in the US and UK, are used for organizing lessons around topics that can be included in classroom activities without causing discomfort, so that the same textbook series can be sold to different parts of the world. Some publishers even have lists of banned topics or rely informally on the acronym PARSNIP (politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, isms, and pork) as a rule of thumb.

The convention of avoidance, then, is related to problems that tend to be purposefully neglected and are those that customarily are the most meaningful issues in real world students' lives. The avoided topics are also close to the ones suggested by OCEM as topics that should be present in Brazilian schools to promote critical literacy. Teachers of English, as well as any other teacher, face, in their daily teaching, educational challenges that go beyond the imagined protected spaces of schools and the imagined worlds portrayed in textbooks. What seems to be relevant in students' lives are not necessarily common topics included in EFL textbooks, such as ‘Mr. Smith's weekend' or ‘global warming', although these can be considered valid topics to be discussed in classrooms.

Considering all these challenges, it is necessary to define the role of teacher education in this process. Teachers should be seen as transformative agents and their education should be focused upon this perspective. This encompasses the traditional contents of sociology of education, psychology of education, educational legislation and other subjects. But, the specific weight on ELT needs to entail criticism of current practices and suggestions for creating new ones.

(JORGE, M. Critical literacy, foreign language teaching and the education about race relations in Brazil. In: The Latin Americanist, vol. 56, 4, December 2012, pp. 79‐90. Available in: https://www.academia.edu . Accessed on September 24th, 2014.)

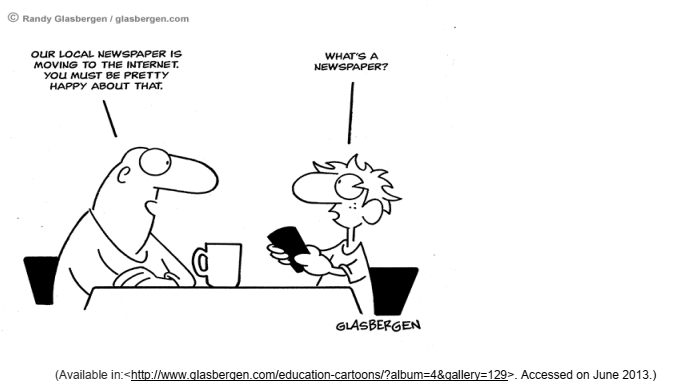

TEXT 5:

Indicate which excerpt taken from text 5 is illustrated by the following cartoon: