Questões de Vestibular de Inglês - Interpretação de texto | Reading comprehension

Foram encontradas 4.863 questões

What are the main ideas of the text?

What can one infer by reading the text?

Beetles and flies are becoming part of the agricultural food chain.

Some visionaries hope that insects will play a big

role in future human diets. Insects are nutritious,

being packed with protein. Unlike hot-blooded

mammals and birds, which use a lot of energy to

keep themselves warm, they are efficient

converters of food into body mass. And in some

parts of the world they are, indeed, eaten already.

Well, maybe. But it will take some serious marketing

to persuade consumers, in the West at least, that

fricasseed locusts or termite burgers are the yummy

must-haves of 21st-century cuisine.

Which sentence below best summarizes the text?

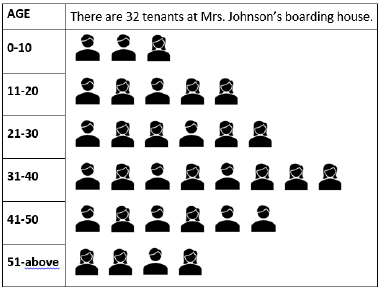

Which alternative shows the best summary of the graph below?

Jane Austen (December 16, 1775 - July 18, 1817) is widely known for her most famous novels. Jane Austen's work features biting social commentary, often delivered with great irony. While her writing was not well known during her lifetime, the 1870 publication of A Memoir of the Life of Jane Austen introduced her to a wider public. Her work is widelyread and admired by modern audiences, who have become quite familiar with Austen's cultural references, including television shows and movies adapted from her work.

Leia os provérbios:

1. Don't count your chickens before they lay eggs.

2. Don't bite the hand that feeds you.

3. Every cloud has a silver lining.

A alternativa que melhor expressa a ideia contida em cada um

dos três provérbios, na ordem em que aparecem, é:

I ain't gonna work on Maggie's farm no more

I ain't gonna work on Maggie's farm no more

Well, I wake up in the morning

Fold my hands and pray for rain

I got a head full of ideas

That are drivin' me insane

It's a shame the way she makes me scrub the floor

I ain't gonna work on Maggie's farm no more

I ain't gonna work for Maggie's brother no more

I ain't gonna work for Maggie's brother no more

Well, he hands you a nickel

He hands you a dime

He asks you with a grin

If you're havin' a good time

Then he fines you every time you slam the door

I ain't gonna work for Maggie's brother no more

I ain't gonna work for Maggie's pa no more

No, I ain't gonna work for Maggie's pa no more

Well, he puts his cigar out in your face just for kicks

His bedroom window it is made out of bricks

The National Guard stands around his door

Ah, I ain't gonna work for Maggie's pa no more, alright

Bob Dylan, "Maggie's Farm", do álbum Bringing it all back home, 1965.

Nestas estrofes, o conjunto de cenas descritas mostra que a

principal dificuldade experimentada pela pessoa cuja história é

contada na letra da música refere-se

I knew TikTok existed, but I didn't fully understand what it was until a few months ago. I also realized that something radical, yet largely invisible, is happening on the internet - with implications we still don't understand.

When I was growing up, I took it for granted that the people who became famous enough to be listened to by a crowd had worked hard for that accolade and generally operated with the support of an institution or an established industry.

The idea that I, as a teenager in my bedroom, might suddenly communicate with 100,000 people or more, would have seemed bizarre.

Today's kids no longer see life in these hierarchical and institutional terms. Yes, their physical worlds are often constrained by parental controls, a lack of access to the outdoors and insane over-scheduling.

But despite that (or, more accurately, in reaction to that), they see the internet as a constantly evolving frontier, where it is still possible for a bold and lucky pioneer to grab some land or find a voice. Most voices on the internet never travel beyond a relatively small network, and much of the content that goes viral on platforms such as TikTok, YouTube or Instagram does so because of unseen institutions at work (for example, a public relations team aiming to boost a celebrity's profile).

Fame can suddenly appear - and then just as suddenly be taken away again, because the audience gets bored, the platform's algorithms change or the cultural trend that a breakout video has tapped into goes out of fashion.

For a teenager, social media can seem like a summer garden at dusk filled with fireflies: spots of lights suddenly flare up and then die down, moving in an unpredictable, capricious display.

Is this a bad thing? We will not know for several years.

Financial Times. 5 February 2020. Adaptado.

I knew TikTok existed, but I didn't fully understand what it was until a few months ago. I also realized that something radical, yet largely invisible, is happening on the internet - with implications we still don't understand.

When I was growing up, I took it for granted that the people who became famous enough to be listened to by a crowd had worked hard for that accolade and generally operated with the support of an institution or an established industry.

The idea that I, as a teenager in my bedroom, might suddenly communicate with 100,000 people or more, would have seemed bizarre.

Today's kids no longer see life in these hierarchical and institutional terms. Yes, their physical worlds are often constrained by parental controls, a lack of access to the outdoors and insane over-scheduling.

But despite that (or, more accurately, in reaction to that), they see the internet as a constantly evolving frontier, where it is still possible for a bold and lucky pioneer to grab some land or find a voice. Most voices on the internet never travel beyond a relatively small network, and much of the content that goes viral on platforms such as TikTok, YouTube or Instagram does so because of unseen institutions at work (for example, a public relations team aiming to boost a celebrity's profile).

Fame can suddenly appear - and then just as suddenly be taken away again, because the audience gets bored, the platform's algorithms change or the cultural trend that a breakout video has tapped into goes out of fashion.

For a teenager, social media can seem like a summer garden at dusk filled with fireflies: spots of lights suddenly flare up and then die down, moving in an unpredictable, capricious display.

Is this a bad thing? We will not know for several years.

Financial Times. 5 February 2020. Adaptado.

How things have changed.

Now disagreements feel deadly serious. Like when your colleague pronounces that wearing a face mask in public is a threat to his liberty. Or when you see that one of your friends has just tweeted that, actually, all lives matter. Before you know it, you’re feeling angry and forming harsh new judgments about your colleagues and friends. Let’s take a collective pause and breathe: there are some ways we can all try to have more civil disagreements in this febrile age of culture wars.

1. ‘Coupling’ and ‘decoupling’

The first is to consider how inclined people are to ‘couple’ or ‘decouple’ topics involving wider political and social factors. Swedish data analyst John Nerst has used the terms to describe the contrasting ways in which people approach contentious issues. Those of us more inclined to ‘couple’ see them as inextricably related to a broader matrix of factors, whereas those more predisposed to ‘decouple’ prefer to consider an issue in isolation. To take a crude example, a decoupler might consider in isolation the question of whether a vaccine provides a degree of immunity to a virus; a coupler, by contrast, would immediately see the issue as inextricably entangled in a mesh of factors, such as pharmaceutical industry power and parental choice.

2.____________________

A study at Arizona State University, U.S., analysed more than 100,000 comments on a forum where users post their views on an issue and invite others to persuade them to change their mind. The researchers found that regardless of the kind of topic, people were more likely to change their mind when confronted with more evidence-based arguments. “Our work may suggest that while attitude change is hard-won, providing facts, statistics and citations for one’s arguments can convince people to change their minds,” they concluded.

3. Just be nicer?

Finally, it’s easier said than done, but let’s all try to be more respectful of and attentive to each other’s positions. We should do this not just for virtuous reasons, but because the more we create that kind of a climate, the more open-minded and intellectually flexible we will all be inclined to be. And then hopefully, collectively, we can start having more constructive disagreements — even in our present very difficult times.