Questões de Vestibular Sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 5.992 questões

Leia a tirinha para responder à questão.

<http://tinyurl.com/hbq57jx> Acesso em: 23.02.2016. Original colorido

Leia a tirinha para responder à questão.

<http://tinyurl.com/hbq57jx> Acesso em: 23.02.2016. Original colorido

Leia a tirinha para responder à questão.

<http://tinyurl.com/hbq57jx> Acesso em: 23.02.2016. Original colorido

No primeiro quadrinho da tirinha, um dos personagens comunica a sua decisão de

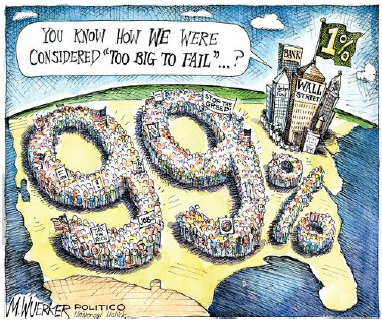

(Disponível em:<http://www.gocomics.com/mattwuerker>. Acesso em: 5 out. 2011.)

Which current social episode is the editorial cartoon an allusion to?

... so that patients do not forgo eating or purge their meals.

First Trader: “I’ve got a stock here that could really excel.” Crowd: “Really excel?” – “Excel?” – “Sell?” – “Sell, sell, sell!” Second Trader: “This is madness! I can’t take this any more! Good bye!” Crowd: “Good bye?” – “Bye?” – “Buy, buy, buy!“

(Disponível em: <www.cartoonstock.com>. Acesso em 04 out. 2011)

De acordo com a charge, a oscilação de preços, oferta e procura no mercado de ações tem origem

Leia o texto para responder a questão.

The Rise of Antibiotic Resistance

By The Editorial Board

May 10, 2014

The World Health Organization has surveyed the growth of antibiotic-resistant germs around the world – the first such survey it has ever conducted – and come up with disturbing findings. In a report issued late last month, the organization found that antimicrobial resistance in bacteria (the main focus of the report), fungi, viruses and parasites is an increasingly serious threat in every part of the world. “A problem so serious that it threatens the achievements of modern medicine,” the organization said. “A post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries can kill, far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century.”

The growth of antibiotic-resistant pathogens means that in ever more cases, standard treatments no longer work, infections are harder or impossible to control, the risk of spreading infections to others is increased, and illnesses and hospital stays are prolonged. All of these drive up the costs of illnesses and the risk of death. The survey sought to determine the scope of the problem by asking countries to submit their most recent surveillance data (114 did so). Unfortunately, the data was glaringly incomplete because few countries track and monitor antibiotic resistance comprehensively, and there is no standard methodology for doing so.

Still, it is clear that major resistance problems have already developed, both for antibiotics that are used routinely and for those deemed “last resort” treatments to cure people when all else has failed. Carbapenem antibiotics, a class of drugs used as a last resort to treat life-threatening infections caused by a common intestinal bacterium, have failed to work in more than half the people treated in some countries. The bacterium is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections such as pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and infections in newborns and intensive-care patients. Similarly, the failure of a last-resort treatment for gonorrhoea has been confirmed in 10 countries, including many with advanced health care systems, such as Australia, Canada, France, Sweden and Britain. And resistance to a class of antibiotics that is routinely used to treat urinary tract infections caused by E. coli is widespread; in some countries the drugs are now ineffective in more than half of the patients treated. This sobering report is intended to kick-start a global campaign to develop tools and standards to track drug resistance, measure its health and economic impact, and design solutions.

The most urgent need is to minimize the overuse of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture, which accelerates the development of resistant strains. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued voluntary guidelines calling on drug companies, animal producers and veterinarians to stop indiscriminately using antibiotics that are important for treating humans on livestock; the drug companies have said they will comply. But the agency, shortsightedly, has appealed a court order requiring it to ban the use of penicillin and two forms of tetracycline by animal producers to promote growth unless they provide proof that it will not promote drug-resistant microbes.

The pharmaceutical industry needs to be encouraged to develop new antibiotics to supplement those that are losing their effectiveness. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society, which represents pharmacists in Britain, called this month for stronger financial incentives. It said that no new class of antibiotics has been discovered since 1987, largely because the financial returns for finding new classes of antibiotics are too low. Unlike lucrative drugs to treat chronic diseases like cancer and cardiovascular ailments, antibiotics are typically taken for a short period of time, and any new drug is apt to be used sparingly and held in reserve to treat patients resistant to existing drugs. Antibiotics have transformed medicine and saved countless lives over the past seven decades. Now, rampant overuse and the lack of new drugs in the pipeline threaten to undermine their effectiveness.

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder a questão.

The Rise of Antibiotic Resistance

By The Editorial Board

May 10, 2014

The World Health Organization has surveyed the growth of antibiotic-resistant germs around the world – the first such survey it has ever conducted – and come up with disturbing findings. In a report issued late last month, the organization found that antimicrobial resistance in bacteria (the main focus of the report), fungi, viruses and parasites is an increasingly serious threat in every part of the world. “A problem so serious that it threatens the achievements of modern medicine,” the organization said. “A post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries can kill, far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century.”

The growth of antibiotic-resistant pathogens means that in ever more cases, standard treatments no longer work, infections are harder or impossible to control, the risk of spreading infections to others is increased, and illnesses and hospital stays are prolonged. All of these drive up the costs of illnesses and the risk of death. The survey sought to determine the scope of the problem by asking countries to submit their most recent surveillance data (114 did so). Unfortunately, the data was glaringly incomplete because few countries track and monitor antibiotic resistance comprehensively, and there is no standard methodology for doing so.

Still, it is clear that major resistance problems have already developed, both for antibiotics that are used routinely and for those deemed “last resort” treatments to cure people when all else has failed. Carbapenem antibiotics, a class of drugs used as a last resort to treat life-threatening infections caused by a common intestinal bacterium, have failed to work in more than half the people treated in some countries. The bacterium is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections such as pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and infections in newborns and intensive-care patients. Similarly, the failure of a last-resort treatment for gonorrhoea has been confirmed in 10 countries, including many with advanced health care systems, such as Australia, Canada, France, Sweden and Britain. And resistance to a class of antibiotics that is routinely used to treat urinary tract infections caused by E. coli is widespread; in some countries the drugs are now ineffective in more than half of the patients treated. This sobering report is intended to kick-start a global campaign to develop tools and standards to track drug resistance, measure its health and economic impact, and design solutions.

The most urgent need is to minimize the overuse of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture, which accelerates the development of resistant strains. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued voluntary guidelines calling on drug companies, animal producers and veterinarians to stop indiscriminately using antibiotics that are important for treating humans on livestock; the drug companies have said they will comply. But the agency, shortsightedly, has appealed a court order requiring it to ban the use of penicillin and two forms of tetracycline by animal producers to promote growth unless they provide proof that it will not promote drug-resistant microbes.

The pharmaceutical industry needs to be encouraged to develop new antibiotics to supplement those that are losing their effectiveness. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society, which represents pharmacists in Britain, called this month for stronger financial incentives. It said that no new class of antibiotics has been discovered since 1987, largely because the financial returns for finding new classes of antibiotics are too low. Unlike lucrative drugs to treat chronic diseases like cancer and cardiovascular ailments, antibiotics are typically taken for a short period of time, and any new drug is apt to be used sparingly and held in reserve to treat patients resistant to existing drugs. Antibiotics have transformed medicine and saved countless lives over the past seven decades. Now, rampant overuse and the lack of new drugs in the pipeline threaten to undermine their effectiveness.

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder a questão.

The Rise of Antibiotic Resistance

By The Editorial Board

May 10, 2014

The World Health Organization has surveyed the growth of antibiotic-resistant germs around the world – the first such survey it has ever conducted – and come up with disturbing findings. In a report issued late last month, the organization found that antimicrobial resistance in bacteria (the main focus of the report), fungi, viruses and parasites is an increasingly serious threat in every part of the world. “A problem so serious that it threatens the achievements of modern medicine,” the organization said. “A post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries can kill, far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century.”

The growth of antibiotic-resistant pathogens means that in ever more cases, standard treatments no longer work, infections are harder or impossible to control, the risk of spreading infections to others is increased, and illnesses and hospital stays are prolonged. All of these drive up the costs of illnesses and the risk of death. The survey sought to determine the scope of the problem by asking countries to submit their most recent surveillance data (114 did so). Unfortunately, the data was glaringly incomplete because few countries track and monitor antibiotic resistance comprehensively, and there is no standard methodology for doing so.

Still, it is clear that major resistance problems have already developed, both for antibiotics that are used routinely and for those deemed “last resort” treatments to cure people when all else has failed. Carbapenem antibiotics, a class of drugs used as a last resort to treat life-threatening infections caused by a common intestinal bacterium, have failed to work in more than half the people treated in some countries. The bacterium is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections such as pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and infections in newborns and intensive-care patients. Similarly, the failure of a last-resort treatment for gonorrhoea has been confirmed in 10 countries, including many with advanced health care systems, such as Australia, Canada, France, Sweden and Britain. And resistance to a class of antibiotics that is routinely used to treat urinary tract infections caused by E. coli is widespread; in some countries the drugs are now ineffective in more than half of the patients treated. This sobering report is intended to kick-start a global campaign to develop tools and standards to track drug resistance, measure its health and economic impact, and design solutions.

The most urgent need is to minimize the overuse of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture, which accelerates the development of resistant strains. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued voluntary guidelines calling on drug companies, animal producers and veterinarians to stop indiscriminately using antibiotics that are important for treating humans on livestock; the drug companies have said they will comply. But the agency, shortsightedly, has appealed a court order requiring it to ban the use of penicillin and two forms of tetracycline by animal producers to promote growth unless they provide proof that it will not promote drug-resistant microbes.

The pharmaceutical industry needs to be encouraged to develop new antibiotics to supplement those that are losing their effectiveness. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society, which represents pharmacists in Britain, called this month for stronger financial incentives. It said that no new class of antibiotics has been discovered since 1987, largely because the financial returns for finding new classes of antibiotics are too low. Unlike lucrative drugs to treat chronic diseases like cancer and cardiovascular ailments, antibiotics are typically taken for a short period of time, and any new drug is apt to be used sparingly and held in reserve to treat patients resistant to existing drugs. Antibiotics have transformed medicine and saved countless lives over the past seven decades. Now, rampant overuse and the lack of new drugs in the pipeline threaten to undermine their effectiveness.

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder a questão.

The Rise of Antibiotic Resistance

By The Editorial Board

May 10, 2014

The World Health Organization has surveyed the growth of antibiotic-resistant germs around the world – the first such survey it has ever conducted – and come up with disturbing findings. In a report issued late last month, the organization found that antimicrobial resistance in bacteria (the main focus of the report), fungi, viruses and parasites is an increasingly serious threat in every part of the world. “A problem so serious that it threatens the achievements of modern medicine,” the organization said. “A post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries can kill, far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century.”

The growth of antibiotic-resistant pathogens means that in ever more cases, standard treatments no longer work, infections are harder or impossible to control, the risk of spreading infections to others is increased, and illnesses and hospital stays are prolonged. All of these drive up the costs of illnesses and the risk of death. The survey sought to determine the scope of the problem by asking countries to submit their most recent surveillance data (114 did so). Unfortunately, the data was glaringly incomplete because few countries track and monitor antibiotic resistance comprehensively, and there is no standard methodology for doing so.

Still, it is clear that major resistance problems have already developed, both for antibiotics that are used routinely and for those deemed “last resort” treatments to cure people when all else has failed. Carbapenem antibiotics, a class of drugs used as a last resort to treat life-threatening infections caused by a common intestinal bacterium, have failed to work in more than half the people treated in some countries. The bacterium is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections such as pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and infections in newborns and intensive-care patients. Similarly, the failure of a last-resort treatment for gonorrhoea has been confirmed in 10 countries, including many with advanced health care systems, such as Australia, Canada, France, Sweden and Britain. And resistance to a class of antibiotics that is routinely used to treat urinary tract infections caused by E. coli is widespread; in some countries the drugs are now ineffective in more than half of the patients treated. This sobering report is intended to kick-start a global campaign to develop tools and standards to track drug resistance, measure its health and economic impact, and design solutions.

The most urgent need is to minimize the overuse of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture, which accelerates the development of resistant strains. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued voluntary guidelines calling on drug companies, animal producers and veterinarians to stop indiscriminately using antibiotics that are important for treating humans on livestock; the drug companies have said they will comply. But the agency, shortsightedly, has appealed a court order requiring it to ban the use of penicillin and two forms of tetracycline by animal producers to promote growth unless they provide proof that it will not promote drug-resistant microbes.

The pharmaceutical industry needs to be encouraged to develop new antibiotics to supplement those that are losing their effectiveness. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society, which represents pharmacists in Britain, called this month for stronger financial incentives. It said that no new class of antibiotics has been discovered since 1987, largely because the financial returns for finding new classes of antibiotics are too low. Unlike lucrative drugs to treat chronic diseases like cancer and cardiovascular ailments, antibiotics are typically taken for a short period of time, and any new drug is apt to be used sparingly and held in reserve to treat patients resistant to existing drugs. Antibiotics have transformed medicine and saved countless lives over the past seven decades. Now, rampant overuse and the lack of new drugs in the pipeline threaten to undermine their effectiveness.

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder a questão.

The Rise of Antibiotic Resistance

By The Editorial Board

May 10, 2014

The World Health Organization has surveyed the growth of antibiotic-resistant germs around the world – the first such survey it has ever conducted – and come up with disturbing findings. In a report issued late last month, the organization found that antimicrobial resistance in bacteria (the main focus of the report), fungi, viruses and parasites is an increasingly serious threat in every part of the world. “A problem so serious that it threatens the achievements of modern medicine,” the organization said. “A post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries can kill, far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century.”

The growth of antibiotic-resistant pathogens means that in ever more cases, standard treatments no longer work, infections are harder or impossible to control, the risk of spreading infections to others is increased, and illnesses and hospital stays are prolonged. All of these drive up the costs of illnesses and the risk of death. The survey sought to determine the scope of the problem by asking countries to submit their most recent surveillance data (114 did so). Unfortunately, the data was glaringly incomplete because few countries track and monitor antibiotic resistance comprehensively, and there is no standard methodology for doing so.

Still, it is clear that major resistance problems have already developed, both for antibiotics that are used routinely and for those deemed “last resort” treatments to cure people when all else has failed. Carbapenem antibiotics, a class of drugs used as a last resort to treat life-threatening infections caused by a common intestinal bacterium, have failed to work in more than half the people treated in some countries. The bacterium is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections such as pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and infections in newborns and intensive-care patients. Similarly, the failure of a last-resort treatment for gonorrhoea has been confirmed in 10 countries, including many with advanced health care systems, such as Australia, Canada, France, Sweden and Britain. And resistance to a class of antibiotics that is routinely used to treat urinary tract infections caused by E. coli is widespread; in some countries the drugs are now ineffective in more than half of the patients treated. This sobering report is intended to kick-start a global campaign to develop tools and standards to track drug resistance, measure its health and economic impact, and design solutions.

The most urgent need is to minimize the overuse of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture, which accelerates the development of resistant strains. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued voluntary guidelines calling on drug companies, animal producers and veterinarians to stop indiscriminately using antibiotics that are important for treating humans on livestock; the drug companies have said they will comply. But the agency, shortsightedly, has appealed a court order requiring it to ban the use of penicillin and two forms of tetracycline by animal producers to promote growth unless they provide proof that it will not promote drug-resistant microbes.

The pharmaceutical industry needs to be encouraged to develop new antibiotics to supplement those that are losing their effectiveness. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society, which represents pharmacists in Britain, called this month for stronger financial incentives. It said that no new class of antibiotics has been discovered since 1987, largely because the financial returns for finding new classes of antibiotics are too low. Unlike lucrative drugs to treat chronic diseases like cancer and cardiovascular ailments, antibiotics are typically taken for a short period of time, and any new drug is apt to be used sparingly and held in reserve to treat patients resistant to existing drugs. Antibiotics have transformed medicine and saved countless lives over the past seven decades. Now, rampant overuse and the lack of new drugs in the pipeline threaten to undermine their effectiveness.

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder a questão.

The Rise of Antibiotic Resistance

By The Editorial Board

May 10, 2014

The World Health Organization has surveyed the growth of antibiotic-resistant germs around the world – the first such survey it has ever conducted – and come up with disturbing findings. In a report issued late last month, the organization found that antimicrobial resistance in bacteria (the main focus of the report), fungi, viruses and parasites is an increasingly serious threat in every part of the world. “A problem so serious that it threatens the achievements of modern medicine,” the organization said. “A post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries can kill, far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century.”

The growth of antibiotic-resistant pathogens means that in ever more cases, standard treatments no longer work, infections are harder or impossible to control, the risk of spreading infections to others is increased, and illnesses and hospital stays are prolonged. All of these drive up the costs of illnesses and the risk of death. The survey sought to determine the scope of the problem by asking countries to submit their most recent surveillance data (114 did so). Unfortunately, the data was glaringly incomplete because few countries track and monitor antibiotic resistance comprehensively, and there is no standard methodology for doing so.

Still, it is clear that major resistance problems have already developed, both for antibiotics that are used routinely and for those deemed “last resort” treatments to cure people when all else has failed. Carbapenem antibiotics, a class of drugs used as a last resort to treat life-threatening infections caused by a common intestinal bacterium, have failed to work in more than half the people treated in some countries. The bacterium is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections such as pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and infections in newborns and intensive-care patients. Similarly, the failure of a last-resort treatment for gonorrhoea has been confirmed in 10 countries, including many with advanced health care systems, such as Australia, Canada, France, Sweden and Britain. And resistance to a class of antibiotics that is routinely used to treat urinary tract infections caused by E. coli is widespread; in some countries the drugs are now ineffective in more than half of the patients treated. This sobering report is intended to kick-start a global campaign to develop tools and standards to track drug resistance, measure its health and economic impact, and design solutions.

The most urgent need is to minimize the overuse of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture, which accelerates the development of resistant strains. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued voluntary guidelines calling on drug companies, animal producers and veterinarians to stop indiscriminately using antibiotics that are important for treating humans on livestock; the drug companies have said they will comply. But the agency, shortsightedly, has appealed a court order requiring it to ban the use of penicillin and two forms of tetracycline by animal producers to promote growth unless they provide proof that it will not promote drug-resistant microbes.

The pharmaceutical industry needs to be encouraged to develop new antibiotics to supplement those that are losing their effectiveness. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society, which represents pharmacists in Britain, called this month for stronger financial incentives. It said that no new class of antibiotics has been discovered since 1987, largely because the financial returns for finding new classes of antibiotics are too low. Unlike lucrative drugs to treat chronic diseases like cancer and cardiovascular ailments, antibiotics are typically taken for a short period of time, and any new drug is apt to be used sparingly and held in reserve to treat patients resistant to existing drugs. Antibiotics have transformed medicine and saved countless lives over the past seven decades. Now, rampant overuse and the lack of new drugs in the pipeline threaten to undermine their effectiveness.

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder a questão.

The Rise of Antibiotic Resistance

By The Editorial Board

May 10, 2014

The World Health Organization has surveyed the growth of antibiotic-resistant germs around the world – the first such survey it has ever conducted – and come up with disturbing findings. In a report issued late last month, the organization found that antimicrobial resistance in bacteria (the main focus of the report), fungi, viruses and parasites is an increasingly serious threat in every part of the world. “A problem so serious that it threatens the achievements of modern medicine,” the organization said. “A post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries can kill, far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century.”

The growth of antibiotic-resistant pathogens means that in ever more cases, standard treatments no longer work, infections are harder or impossible to control, the risk of spreading infections to others is increased, and illnesses and hospital stays are prolonged. All of these drive up the costs of illnesses and the risk of death. The survey sought to determine the scope of the problem by asking countries to submit their most recent surveillance data (114 did so). Unfortunately, the data was glaringly incomplete because few countries track and monitor antibiotic resistance comprehensively, and there is no standard methodology for doing so.

Still, it is clear that major resistance problems have already developed, both for antibiotics that are used routinely and for those deemed “last resort” treatments to cure people when all else has failed. Carbapenem antibiotics, a class of drugs used as a last resort to treat life-threatening infections caused by a common intestinal bacterium, have failed to work in more than half the people treated in some countries. The bacterium is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections such as pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and infections in newborns and intensive-care patients. Similarly, the failure of a last-resort treatment for gonorrhoea has been confirmed in 10 countries, including many with advanced health care systems, such as Australia, Canada, France, Sweden and Britain. And resistance to a class of antibiotics that is routinely used to treat urinary tract infections caused by E. coli is widespread; in some countries the drugs are now ineffective in more than half of the patients treated. This sobering report is intended to kick-start a global campaign to develop tools and standards to track drug resistance, measure its health and economic impact, and design solutions.

The most urgent need is to minimize the overuse of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture, which accelerates the development of resistant strains. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued voluntary guidelines calling on drug companies, animal producers and veterinarians to stop indiscriminately using antibiotics that are important for treating humans on livestock; the drug companies have said they will comply. But the agency, shortsightedly, has appealed a court order requiring it to ban the use of penicillin and two forms of tetracycline by animal producers to promote growth unless they provide proof that it will not promote drug-resistant microbes.

The pharmaceutical industry needs to be encouraged to develop new antibiotics to supplement those that are losing their effectiveness. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society, which represents pharmacists in Britain, called this month for stronger financial incentives. It said that no new class of antibiotics has been discovered since 1987, largely because the financial returns for finding new classes of antibiotics are too low. Unlike lucrative drugs to treat chronic diseases like cancer and cardiovascular ailments, antibiotics are typically taken for a short period of time, and any new drug is apt to be used sparingly and held in reserve to treat patients resistant to existing drugs. Antibiotics have transformed medicine and saved countless lives over the past seven decades. Now, rampant overuse and the lack of new drugs in the pipeline threaten to undermine their effectiveness.

(www.nytimes.com. Adaptado.)

Leia o texto para responder a questão.

Healthy choices

How do we reduce waistlines in a country where we traditionally do not like telling individuals what to do?

By Telegraph View

22 Aug 2014

Duncan Selbie, the Chief Executive of Public Health

England, suggests that parents feed their children

from smaller plates. Photo: Alamy

Every new piece of information about Britain’s weight problem makes for ever more depressing reading. Duncan Selbie, the Chief Executive of Public Health England, today tells us that by 2034 some six million Britons will suffer from diabetes. Of course, many people develop diabetes through no fault of their own. But Mr Selbie’s research concludes that if the levels of obesity returned to their 1994 levels, 1.7 million fewer people would suffer from the condition.

Given that fighting diabetes already drains the National Health Service (NHS) by more than £1.5 million, or 10 per cent of its budget for England, the impact upon the Treasury in 20 years’ time from unhealthy lifestyles could be catastrophic. Bad health not only impacts on the individual but also on the rest of the community.

Diagnosis of the challenge is straightforward. The tougher question is what to do about reducing waistlines in a country where we traditionally do not like telling individuals what to do.

It is interesting to note that Mr Selbie does not ascribe to the Big Brother approach of ceaseless legislation and nannying. Rather, he is keen to promote choices – making the case passionately that people should be encouraged to embrace good health. One of his suggestions is that parents feed their children from smaller plates. That way the child can clear his or her plate, as ordered, without actually consuming too much. Like all good ideas, this is rooted in common sense.

(www.telegraph.co.uk. Adaptado.)