Questões de Vestibular Sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 5.992 questões

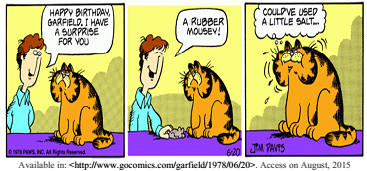

When Garfield says “could’ve used a little salt”, what is he expressing?

Os documentos descobertos em Vindolanda

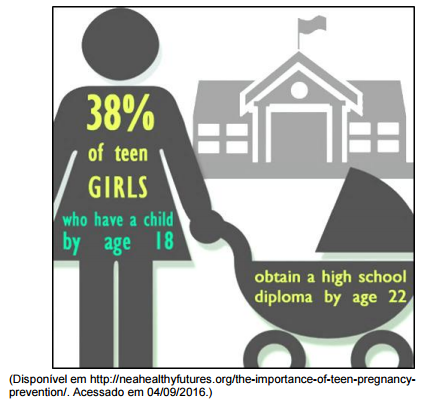

Depreende-se das informações da figura que

Harry Potter is the best selling book series of all time. But it’s had its reproaches. Various Christian groups claimed the books promoted paganism and witchcraft to children. Washington Post book critic Ron Charles called the fact that adults were also hooked on Potter a "bad case of cultural infantilism.” Charles and others also cited a certain artistic banality in massively commercial story-telling, while others criticized Hogwarts, the wizardry academy attended by Potter, for only rewarding innate talents. The Anglo-American writer Christopher Hitchens, on the other hand, praised J. K. Rowling for freeing English children’s literature from dreams of riches and class and snobbery and giving us a world of youthful democracy and diversity. A growing body of evidence suggests that reading Rowling’s work, at least as a youth, might be a good thing. (Adaptado de http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-everyone-shouldread-harry-potter/. Acessado em 02/09/2016.)

A leitura do excerto permite concluir adequadamente que:

Ranking Universities by ‘Greenness’

Universities these days are working hard to improve their sustainability credentials, with efforts that include wind power, organic food and competitions to save energy. They are also adding courses related to sustainability and energy. But which university is the greenest?

Several ranking systems have emerged to offer their take. The Princeton Review recently came out with its second annual green ratings. Fifteen colleges earned the highest possible score — including Harvard, Yale and the University of California, Berkeley.

Another group, the Sustainable Endowment Institute’s GreenReportCard.org, rates colleges on several different areas of green compliance, such as recycling, student involvement and green building. Its top grade for overall excellence, an A-, was earned by 15 schools.

(Adaptado de http://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/08/20/ranking-universities-bygreenness/?_r=0.

Acessado em 31/08/2016.)

Conforme o texto, universidades norte-americanas estão

se empenhando para

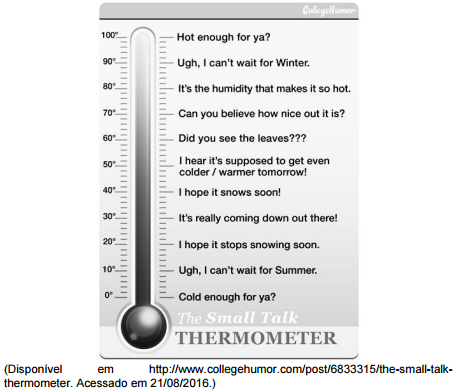

Considerando o nome da figura - “The Small Talk

Thermometer” -, pode-se depreender que a expressão “small

talk” se refere a

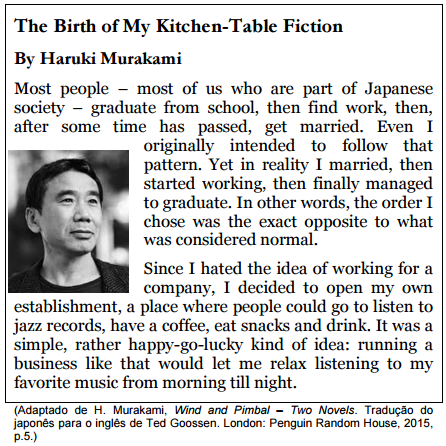

O autor do texto

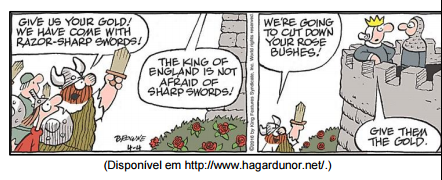

A tirinha ironiza uma suposta característica dos ingleses:

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXT

Nearly 250 million young children across the world – 43% of under-fives – are unlikely to fulfil their potential as adults because of stunting and extreme poverty, new figures show.

The first three years of life are crucial to a child’s development, according to a series of research papers published in the Lancet medical journal, which says there are also economic costs to the failure to help them grow. Those who do not get the nutrition, care and stimulation they need will earn about 26% less than others as adults.

“The costs of not acting immediately to expand services to improve early childhood development are high for individuals and their families, as well as for societies,” say the researchers. The cost to some countries in GDP (gross domestic product), they estimate, is as much as twice their spending on healthcare.

The figures come as the World Bank prepares for a summit meeting with finance ministers around the globe to discuss how nurturing children in their early years will help their countries’ economic development. The World Bank president, Jim Yong Kim, has told the Guardian that he intends to use the World Economic Forum in Davos each year to name and shame countries that do not reduce their high stunting rates.

The Lancet series says the first 24 months of life are the critical time for avoiding stunting. Undernourished children living in extreme poverty end up small and their brain development is affected, so that they find it hard to learn. “Some catch-up is possible in height-for-age after 24 months, with uncertain cognitive gains,” says one of the papers.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 66% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor development because of stunting and poverty. In south Asia, the figure is 65%, and 18% in the Caribbean and South America.

Mothers need to be well nourished to give their babies a good start in life and be able to breastfeed. Families need help to give children the nutrition and nurturing they need, say researchers. That includes breastfeeding, free pre-school education – which is available in only two-thirds of high-income countries – paid leave for parents and a minimum wage to pull more families out of poverty.

There are children at risk in all countries, rich and poor. The series points to early childhood programs that have been effective, including Sure Start in the UK, Early Head Start in the US, Chile’s Crece Contigo and Grade R in South Africa

In a Comment piece in the journal, Dr Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization, Anthony Lake, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund, and Keith Hansen, vice-president for human development at the World Bank, write: “The early childhood agenda is truly global, because the need is not limited to low-income countries. Children living in disadvantaged households in middle-income and wealthy countries are also at risk.

“In targeting our investments, we should give priority to populations in the greatest need, such as families and children in extreme poverty and those who require humanitarian assistance. In addition, we have to build more resilient systems in vulnerable communities to mitigate the disruptive influence of natural disasters, fragility, conflict, and violence.”

Wanda Wyporska, executive director of the Equality Trust, said: “It’s no surprise that the richer you are, the better your health is likely to be”. But the chasm of health inequality between rich and poor has widened in recent years.

“Being born into a poor family shouldn’t mean decades of poorer health and even premature death, but that’s the shameful reality of the UK’s health gap. If you rank neighborhoods in the UK from the richest to the poorest, you have almost perfectly ranked health from the best to the worst.”

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/04

TEXTO 8

IX

Horas depois, teve Rubião um pensamento horrível. Podiam crer que ele próprio incitara o amigo à viagem, para o fim de o matar mais depressa, e entrar na posse do legado, se é que realmente estava incluso no testamento. Sentiu remorsos. Por que não empregou todas as forças, para contê-lo? Viu o cadáver do Quincas Borba, pálido, hediondo, fitando nele um olhar vingativo; resolveu, se acaso o fatal desfecho se desse em viagem, abrir mão do legado.

Pela sua parte o cão vivia farejando, ganindo, querendo fugir; não podia dormir quieto, levantava-se muitas vezes, à noite, percorria a casa, e tornava ao seu canto. De manhã, Rubião chamava-o à cama, e o cão acudia alegre; imaginava que era o próprio dono; via depois que não era, mas aceitava as carícias, e fazia-lhe outras, como se Rubião tivesse de levar as suas ao amigo, ou trazê-lo para ali. Demais, havia-se-lhe afeiçoado também, e para ele era a ponte que o ligava à existência anterior. Não comeu durante os primeiros dias. Suportando menos a sede, Rubião pôde alcançar que bebesse leite; foi a única alimentação por algum tempo. Mais tarde, passava as horas, calado, triste, enrolado em si mesmo, ou então com o corpo estendido e a cabeça entre as mãos.

Quando o médico voltou, ficou espantado da temeridade do doente; deviam tê-lo impedido de sair; a morte era certa.

— Certa?

— Mais tarde ou mais cedo. Levou o tal cachorro?

— Não, senhor, está comigo; pediu que cuidasse dele, e chorou, olhe que chorou que foi um nunca acabar. Verdade é, disse ainda Rubião para defender o enfermo, verdade é que o cachorro merece a estima do dono; parece gente.

O médico tirou o largo chapéu de palha para concertar a fita; depois sorriu. Gente? Com que então parecia gente? Rubião insistia, depois explicava; não era gente como a outra gente, mas tinha coisas de sentimento, e até de juízo. Olhe, ia contar-lhe uma...

— Não, homem, não, logo, logo, vou a um doente de erisipela... Se vierem cartas dele, e não forem reservadas, desejo vê-las, ouviu? E lembranças ao cachorro, concluiu saindo.

Algumas pessoas começaram a mofar do Rubião e da singular incumbência de guardar um cão em vez de ser o cão que o guardasse a ele. Vinha a risota, choviam as alcunhas. Em que havia de dar o professor! sentinela de cachorro! Rubião tinha medo da opinião pública. Com efeito, parecia-lhe ridículo; fugia aos olhos estranhos, olhava com fastio para o animal, dava-se ao diabo, arrenegava da vida. Não tivesse a esperança de um legado, pequeno que fosse. Era impossível que lhe não deixasse uma lembrança.

(ASSIS, Machado de. Quincas Borba. São Paulo: Ática, 2011. p. 30-31.)

(Available at http://c.merriam-webster.com/medlineplus/erysipelas., accessed on July 14th, 2016.)

Choose the appropriate alternative:

TEXTO 7

O mistério dos hippies desaparecidos

Ide ao Mercadão da Travessa do Carmo. Que vereis? O alegre, o pitoresco, o colorido. Admirai a excelente organização: cada artesão em seu quadrado, exibindo belos trabalhos.

Mas... Nada vos chama a atenção?

Não? Neste caso, pergunto-vos: onde estão os hippies da Praça Dom Feliciano? Isso mesmo, aqueles que ficavam na frente da Santa Casa. Onde estão? Não sabeis?

O homem de cinza sabe.

O homem de cinza vinha todos os dias à Praça Dom Feliciano. Ficava muito tempo olhando os hippies, que não lhe davam maior atenção. O homem, ao contrário, parecia muito interessado neles: examinava os objetos expostos, indagava por preços, por detalhes da manufatura. E anotava tudo numa caderneta de capa preta. Um dia perguntou aos hippies onde moravam. Por aí, respondeu um rapaz. Numa comuna? — perguntou o homem. Não, não era em nenhuma comuna; na realidade, estavam ao relento. O homem então disse que eles deveriam morar juntos numa comuna. Ficaria mais fácil, mais prático. O rapaz concordou. Não estava com muita vontade de falar; contudo, acrescentou, depois de uma pausa, que o problema era encontrar o lugar para a comuna.

Não é problema, disse o homem; eu tenho uma chácara lá na Vila Nova, com uma boa casa, gramados, árvores frutíferas. Se vocês quiserem, podem ficar lá. No amor? — perguntou o rapaz.

— No amor, bicho — respondeu o homem, rindo. Só quero que vocês tomem conta da casa. Os hippies confabularam entre si e resolveram aceitar. O homem levou-os — eram doze, entre rapazes e moças — à chácara, numa camioneta Veraneio. Deixou-os lá.

Durante algum tempo não apareceu. Mas, num domingo, deu as caras. Conversou com os jovens sobre a chácara, contou histórias interessantes. Finalmente, pediu para ver o que tinham feito de artesanato. Examinou as peças atentamente e disse:

— Posso dar uma sugestão? Eles concordaram. Como não haveriam de concordar? Mas foi assim que começou. O homem organizou-os em equipes: a equipe dos cintos, a equipe das pulseiras, a equipe das bolsas.

Ensinou-os a trabalhar pelo sistema de linha de montagem; racionalizou cada tarefa, cada atividade.

Disciplinou a vida deles, também. Centralizou todo o consumo de tóxicos. Fornecia drogas mediante vales, resgatados ao fim do mês, conforme a produção. Permitiu que se vestissem como desejavam, mas era rígido na escala de trabalho. Seis dias por semana, folga às quartas — nos domingos tinham de trabalhar. Nestes dias, o homem de cinza admitia visitantes na chácara, mediante o pagamento de ingressos. Um guia especialmente treinado acompanhava-os, explicando todos os detalhes acerca dos hippies, estes seres curiosos.

O homem de cinza já era muito rico, mas agora está multimilionário. É que organizou uma firma, e exporta para os Estados Unidos e para o Mercado Comum Europeu cintos, pulseiras e bolsas.

Parece que, para esses artigos, não há sobretaxa de exportações. Escreveu um livro — Minha Vida Entre os Hippies — que tem se constituído em autêntico êxito de livraria; uma adaptação para a televisão, sob forma de novela, está quase pronta. E quem ouviu a trilha sonora, garante que é um estouro.

Tem apenas um temor, este homem. É que um dos hippies, de uma hora para outra, cortou o cabelo, passou a tomar banho — e usa agora um decente terno cinza. Por enquanto ainda não se manifestou; mas trata-se — o homem de cinza está convencido disto — de um autêntico contestador.

(SCLIAR, Moacyr. Melhores contos. São Paulo: Global, 2003.

p. 130-132.)

Match the columns to form statements about “hippies”:

I - They usually sell...

II - They were young people in the 1960s and 1970s who...

III - They try to live...

IV - They often have...

( ) …long hair and many of them take drugs.

( ) …rejected conventional ways of living, dressing, and behaving.

( ) …based on peace and love.

( ) …handcraft.

The right sequence is: