Questões de Concurso

Sobre interpretação de texto | reading comprehension em inglês

Foram encontradas 9.443 questões

Text CB1A2-II

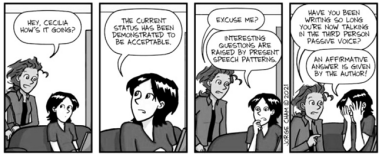

Jorge Cham. Piled higher and deeper. Internet: <www.phdcomics.com>.

Text CB1A2-I

Although an oft-cited poll showed that 85% of Americans approve of organ donation, less than half had made a decision about donating, and fewer still (28%) had granted permission by signing a donor card, a pattern also observed in Germany, Spain, and Sweden. Given the shortage of donors, the gap between approval and action is a matter of life and death.

What drives the decision to become a potential donor? Within the European Union, donation rates vary by nearly an order of magnitude across countries and these differences are stable from year to year. Even when controlling for variables such as transplant infrastructure, economic and educational status, and religion, large differences in donation rates persist. Why?

Most public policy choices have a no-action default, that is, a condition is imposed when an individual fails to make a decision. In the case of organ donation, European countries have one of two default policies. In presumed-consent states, people are organ donors unless they register not to be, and in explicitconsent countries, nobody is an organ donor without registering to be one.

We examined the rate of agreement to become a donor across European countries with explicit and presumed consent laws. If preferences concerning organ donation are strong, we would expect defaults to have little or no effect. However, defaults appear to make a large difference: the four opt-in countries (Denmark, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany) had lower rates than the six opt-out countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Sweden). The two distributions have no overlap, and nearly 60 percentage points separate the two groups

Our data suggest changes in defaults could increase donations in the United States of additional thousands of donors a year. Because each donor can donate for about three transplants, the consequences are substantial in lives saved. Our results stand in contrast with the suggestion that defaults do not matter. Policy-makers performing analysis in this and other domains should consider that defaults make a difference.

Eric J. Johnson; Daniel Goldstein. Do Defaults Save Lives?

Internet: <www.dangoldstein.com> (adapted).

Text CB1A2-I

Although an oft-cited poll showed that 85% of Americans approve of organ donation, less than half had made a decision about donating, and fewer still (28%) had granted permission by signing a donor card, a pattern also observed in Germany, Spain, and Sweden. Given the shortage of donors, the gap between approval and action is a matter of life and death.

What drives the decision to become a potential donor? Within the European Union, donation rates vary by nearly an order of magnitude across countries and these differences are stable from year to year. Even when controlling for variables such as transplant infrastructure, economic and educational status, and religion, large differences in donation rates persist. Why?

Most public policy choices have a no-action default, that is, a condition is imposed when an individual fails to make a decision. In the case of organ donation, European countries have one of two default policies. In presumed-consent states, people are organ donors unless they register not to be, and in explicitconsent countries, nobody is an organ donor without registering to be one.

We examined the rate of agreement to become a donor across European countries with explicit and presumed consent laws. If preferences concerning organ donation are strong, we would expect defaults to have little or no effect. However, defaults appear to make a large difference: the four opt-in countries (Denmark, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany) had lower rates than the six opt-out countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Sweden). The two distributions have no overlap, and nearly 60 percentage points separate the two groups

Our data suggest changes in defaults could increase donations in the United States of additional thousands of donors a year. Because each donor can donate for about three transplants, the consequences are substantial in lives saved. Our results stand in contrast with the suggestion that defaults do not matter. Policy-makers performing analysis in this and other domains should consider that defaults make a difference.

Eric J. Johnson; Daniel Goldstein. Do Defaults Save Lives?

Internet: <www.dangoldstein.com> (adapted).

Text CB1A2-I

Although an oft-cited poll showed that 85% of Americans approve of organ donation, less than half had made a decision about donating, and fewer still (28%) had granted permission by signing a donor card, a pattern also observed in Germany, Spain, and Sweden. Given the shortage of donors, the gap between approval and action is a matter of life and death.

What drives the decision to become a potential donor? Within the European Union, donation rates vary by nearly an order of magnitude across countries and these differences are stable from year to year. Even when controlling for variables such as transplant infrastructure, economic and educational status, and religion, large differences in donation rates persist. Why?

Most public policy choices have a no-action default, that is, a condition is imposed when an individual fails to make a decision. In the case of organ donation, European countries have one of two default policies. In presumed-consent states, people are organ donors unless they register not to be, and in explicitconsent countries, nobody is an organ donor without registering to be one.

We examined the rate of agreement to become a donor across European countries with explicit and presumed consent laws. If preferences concerning organ donation are strong, we would expect defaults to have little or no effect. However, defaults appear to make a large difference: the four opt-in countries (Denmark, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany) had lower rates than the six opt-out countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Sweden). The two distributions have no overlap, and nearly 60 percentage points separate the two groups

Our data suggest changes in defaults could increase donations in the United States of additional thousands of donors a year. Because each donor can donate for about three transplants, the consequences are substantial in lives saved. Our results stand in contrast with the suggestion that defaults do not matter. Policy-makers performing analysis in this and other domains should consider that defaults make a difference.

Eric J. Johnson; Daniel Goldstein. Do Defaults Save Lives?

Internet: <www.dangoldstein.com> (adapted).

Text CB1A2-I

Although an oft-cited poll showed that 85% of Americans approve of organ donation, less than half had made a decision about donating, and fewer still (28%) had granted permission by signing a donor card, a pattern also observed in Germany, Spain, and Sweden. Given the shortage of donors, the gap between approval and action is a matter of life and death.

What drives the decision to become a potential donor? Within the European Union, donation rates vary by nearly an order of magnitude across countries and these differences are stable from year to year. Even when controlling for variables such as transplant infrastructure, economic and educational status, and religion, large differences in donation rates persist. Why?

Most public policy choices have a no-action default, that is, a condition is imposed when an individual fails to make a decision. In the case of organ donation, European countries have one of two default policies. In presumed-consent states, people are organ donors unless they register not to be, and in explicitconsent countries, nobody is an organ donor without registering to be one.

We examined the rate of agreement to become a donor across European countries with explicit and presumed consent laws. If preferences concerning organ donation are strong, we would expect defaults to have little or no effect. However, defaults appear to make a large difference: the four opt-in countries (Denmark, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany) had lower rates than the six opt-out countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Sweden). The two distributions have no overlap, and nearly 60 percentage points separate the two groups

Our data suggest changes in defaults could increase donations in the United States of additional thousands of donors a year. Because each donor can donate for about three transplants, the consequences are substantial in lives saved. Our results stand in contrast with the suggestion that defaults do not matter. Policy-makers performing analysis in this and other domains should consider that defaults make a difference.

Eric J. Johnson; Daniel Goldstein. Do Defaults Save Lives?

Internet: <www.dangoldstein.com> (adapted).

Text CB1A2-I

Although an oft-cited poll showed that 85% of Americans approve of organ donation, less than half had made a decision about donating, and fewer still (28%) had granted permission by signing a donor card, a pattern also observed in Germany, Spain, and Sweden. Given the shortage of donors, the gap between approval and action is a matter of life and death.

What drives the decision to become a potential donor? Within the European Union, donation rates vary by nearly an order of magnitude across countries and these differences are stable from year to year. Even when controlling for variables such as transplant infrastructure, economic and educational status, and religion, large differences in donation rates persist. Why?

Most public policy choices have a no-action default, that is, a condition is imposed when an individual fails to make a decision. In the case of organ donation, European countries have one of two default policies. In presumed-consent states, people are organ donors unless they register not to be, and in explicitconsent countries, nobody is an organ donor without registering to be one.

We examined the rate of agreement to become a donor across European countries with explicit and presumed consent laws. If preferences concerning organ donation are strong, we would expect defaults to have little or no effect. However, defaults appear to make a large difference: the four opt-in countries (Denmark, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany) had lower rates than the six opt-out countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Sweden). The two distributions have no overlap, and nearly 60 percentage points separate the two groups

Our data suggest changes in defaults could increase donations in the United States of additional thousands of donors a year. Because each donor can donate for about three transplants, the consequences are substantial in lives saved. Our results stand in contrast with the suggestion that defaults do not matter. Policy-makers performing analysis in this and other domains should consider that defaults make a difference.

Eric J. Johnson; Daniel Goldstein. Do Defaults Save Lives?

Internet: <www.dangoldstein.com> (adapted).

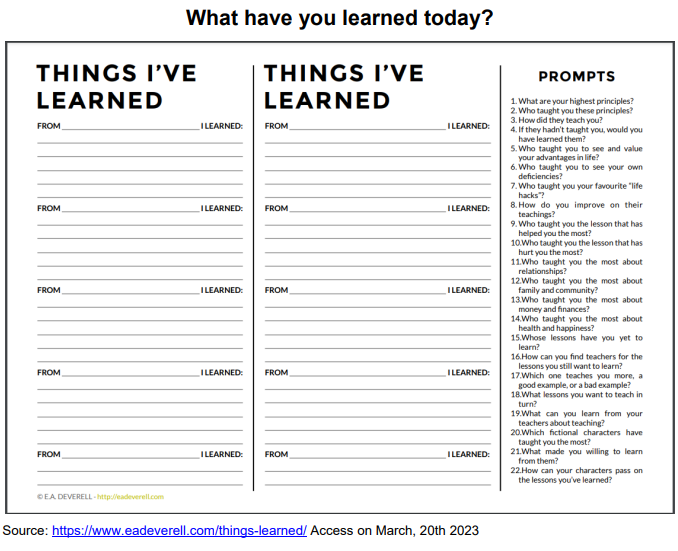

B. The verb tense in the question “What have you learned today?” was used to talk about:

“Baptista: Gentlemen, importune me no farther, For how I firmly am resolu'd you know: That is, not to bestow my yongest daughter, Before I haue a husband for the elder: If either of you both loue Katherina, Because I know you well, and loue you well, Leaue shall you haue to court her at your pleasure.”

Source: https://firstfolio.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/download/text-pdfs/F-shr.pdf

B. In this context, the word “bestow” is closest in meaning to:

I – Even though she read Pride and Prejudice, she does not remember all the story. II – “Mr Darcy, who was leaning against the mantelpiece with these eyes fixed on her face, seemed to catch her words with no less resentment than surprize.” (AUSTEN, 2013, p. 184). III – “It will be no use to us if twenty such should come, since you will not visit them.” (AUSTEN, 2013, p. 3). IV – “The two ladies were delighted to see their dear friend again, […] since they had met […]” (AUSTEN, 2013, p. 78).

It´s possible to observe a multi-dimensional meaning in the title, “I, too” in the lines that open and close the poem. If you hear the word as the number “two”, it can be inferred to someone who:

I. The poem expresses how he felt like an unforgotten American citizen because of his skin color. ( )

II. Hughes proclaims that he, too, is an American, even though the dominant members of society are constantly pushing him aside and hiding him away because he is an African American. ( ) III. Even though Hughes feels ostracized because of his job in the kitchen, he still sings like an American.( )

IV. Although short in length, it delivers a powerful message about how many African Americans have been working in America.( )

V. He hopes white people will be ashamed of the way they have treated African Americans, and they will realize they are also a part of the country. ( )

B. Now, choose the correct alternative.

Based on information from text 2, it is correct to affirm that the illustration:

Text 2

I. Virtual offices are an option for companies that adopt a 100% remote strategy only. II. Virtual offices cost as much as renting office space. III. Employees working in a virtual office can work from home or other places. IV. Physical offices offer more opportunities for face-to-face communication.

( ) Expats in Indonesia are less satisfied with their disposable household income than expats globally. ( ) Comparing to global results, it is considered easy to find a house in Indonesia, but also more expensive. ( ) Expats in Taiwan are happy with the healthcare system: costs are not excessive, and it is easy to access when they need it. ( ) Taiwan has a high ranking in the Working Abroad Index due to the local business culture.

The correct order of filling the parentheses, from top to bottom, is: