Questões de Concurso

Para seplag-se

Foram encontradas 150 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

I. Uma estrutura argumentativa é construída com uma ou mais premissas e uma conclusão. II. Caso uma premissa seja falsa em qualquer situação, qualquer conclusão que se baseie nela será sempre inválida. III. Uma estrutura argumentativa necessita ao menos de duas premissas para que possa ser considerada válida.

Estão corretas as afirmativas:

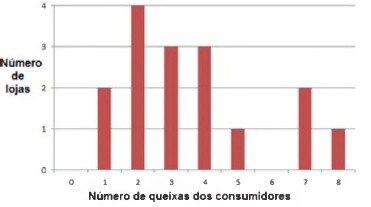

Figura 1: Gráfico do número de queixas por loja.

Baseando-se em sua análise, assinale a alternativa correta:

For the question read the text below:

People are getting poorer’: hunger and homelessness as Brazil crisis deepens

Unemployment and social instability threaten unwelcome return to the past in recession-hit country once seen as a model for developing economies.

It wasn’t yet 5am when Miriam Gomes drove up to Happy Little Angel, the social project she runs in the scruffy Cidade Nova neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro, but the queue for her weekly food handout was already a hundred yards long.

Some had slept outside - those among Rio’s growing army of homeless people, or who lived too far away to get there by 6.30am, when those registered could start collecting a bag of vegetables, fruit, rice, beans, pasta, milk and biscuits, and a little chocolate.

These are some of the victims of a worsening problem in a country once praised for reducing poverty, but where the numbers of poor are climbing again.

Brazil has slumped into its worst recession for decades, with 14 million people unemployed.

There are a lot more people on the street,” said Gomes, 53, who bought the house where Little Happy Angel is based with an inheritance, and lives off her late father’s military pension.

Some of those Gomes helps benefit from a cash transfer scheme called the family allowance, but still struggle to make ends meet. Others are among the 1.1 million families the government removed from the programme last year for what it called “irregularities”.

Among the latter is Vera dos Santos, 43, who lost her job as a maid two and a half years ago, has three teenage children to feed, and recently had her allowance stopped. “My financial situation is difficult,” she said.

Brazil celebrated its removal from the UN hunger map in 2014. Now it is in danger, a new report warns, of being reinstated.

“If we don’t take the due providences, Brazil will go back to the hunger map,” said Francisco Menezes, an economist and one of the authors of a progress report on the 2030 sustainable development agenda, presented recently to the UN by a group of two dozen non-government groups and research institutes, and released in full later this month.

“People are getting poorer,” said Menezes.

That was supposed to be Brazil’s past. When leftwing leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva swept to power on a wave of popular support in 2002, he promised three meals a day to all Brazilians. During his eight years of rule, and a further four by his chosen successor, Dilma Rousseff, 36 million Brazilians escaped poverty with the help of acclaimed social policies like the family allowance.

Rising commodities prices and the feverish consumer spending of a new, lower-middle class contributed to a booming economy. Those living below the poverty line fell from 25% in 2004 to 8% in 2014, when Rousseff faced re-election, according to figures from the social policy centre at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, a leading business school.

By then, though, the economy was already beginning to retract. Commodities prices fell when Rousseff secured a narrow win, with concern growing over her interventionist economic policy and soaring public spending.

By 2015, unemployment was climbing and Brazil had sunk into its deepest recession since the 1930s. The country was stripped of its investment grade. In 2016 Rousseff was impeached, ostensibly for breaking budget rules. But the process was driven by the recession and a vast corruption crisis at state-run oil company Petrobras in which many from Rousseff’s Workers’ party and its Congress allies were embroiled. By then, the number of Brazilians living in poverty had risen to an estimated 11%. “Without doubt, it is a regression,” said Marcelo Neri, director of the Vargas Foundation’s social policy centre.

Michel Temer, Rousseff’s former vice-president, took overand began cutting costs. Last December, a 20-year cap was introduced on public spending. Congress is debating reforms to Brazil’s generous pensions system. Liberal economists argue that without these reforms, Brazil will be unable to overcome its deficit and get back to growth.

The progress report argued that these austerity measures will increase poverty in Brazil and said the country should reduce other costs and adopt a fairer tax system (the highest tax rate in this deeply unequal country is 27.5%). Menezes calculated that, had the spending cap been in place in 2003, Brazil would have had 68% less to spend on social programmes between 2003 and 2015.

Meanwhile, the poor keep getting poorer. This was evident on a recent morning in a corner of Borel, a Rio favela where ramshackle wooden shacks without running water or sewage cling to a muddy hillside. Welington de Souza, a 39-year-old resident, said more homes are being built in the improvised, low-income community, where people work selling tin cans, plastic bottles and cardboard they pick off the street.

People are starting the same line of informal, cash-in-hand work, which they call “recycling”, in growing numbers. “Because of the unemployment, people are having to get by,” said De Souza, who lives with his pregnant partner Karla Santos, 19, and her son Carlos Eduardo, four, and did electrical and cleaning jobs before work dried up.

Santos’s sister, Edeane Silva, 24, lives next door with her partner Sérgio Conceição, 39, and their three young children. Their fridge has broken and water floods under the door when it rains, said Silva. Since her £101 a month family allowance was stopped, she has been “recycling” with Conceição, leaving her baby boy with her mother.

“Sometimes I think I need some meat on the table, and I don’t come home until I get it,” Conceição said. “I have to have faith.”

What Brazilians lack is faith that their politicians have any ability to resolve the mess the country is in and tackle its rising poverty. As graft scandals multiply, most are too busy trying to save themselves. Earlier this year, investigations were authorised into eight of Temer’s ministers. On 2 August, the lower house of Congress will vote on whether to authorise a trial of the president himself on corruption charges.

Temer’s centrist PMDB party has run Rio’s state government since 2007. Its former governor Sérgio Cabral is in jail, accused of pocketing substantial bribes, while the state government is broke and months in arrears with salaries. Unions have been organising food donations for hungry staff.

All of which has fed into an increasingly chaotic environment, where new legislation threatens advances in food security, as well as undermining health, education and social security services, the progress report warned.

“There is a generalised lack of confidence in relation to the political class, the justice system, and the executive and legislative powers,” said the report’s authors, adding that “the most vulnerable populations” were among “the most prejudiced”.

People are getting poorer’: hunger and homelessness as Brazil

crisis deepens. The Guardian, 2017. Disponível em: <https://www. theauardian.com/alobal-development/2017/iul/19/people-aettinapoorer-hunaer-homelessness-brazil-crisis>

For the question read the text below:

People are getting poorer’: hunger and homelessness as Brazil crisis deepens

Unemployment and social instability threaten unwelcome return to the past in recession-hit country once seen as a model for developing economies.

It wasn’t yet 5am when Miriam Gomes drove up to Happy Little Angel, the social project she runs in the scruffy Cidade Nova neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro, but the queue for her weekly food handout was already a hundred yards long.

Some had slept outside - those among Rio’s growing army of homeless people, or who lived too far away to get there by 6.30am, when those registered could start collecting a bag of vegetables, fruit, rice, beans, pasta, milk and biscuits, and a little chocolate.

These are some of the victims of a worsening problem in a country once praised for reducing poverty, but where the numbers of poor are climbing again.

Brazil has slumped into its worst recession for decades, with 14 million people unemployed.

There are a lot more people on the street,” said Gomes, 53, who bought the house where Little Happy Angel is based with an inheritance, and lives off her late father’s military pension.

Some of those Gomes helps benefit from a cash transfer scheme called the family allowance, but still struggle to make ends meet. Others are among the 1.1 million families the government removed from the programme last year for what it called “irregularities”.

Among the latter is Vera dos Santos, 43, who lost her job as a maid two and a half years ago, has three teenage children to feed, and recently had her allowance stopped. “My financial situation is difficult,” she said.

Brazil celebrated its removal from the UN hunger map in 2014. Now it is in danger, a new report warns, of being reinstated.

“If we don’t take the due providences, Brazil will go back to the hunger map,” said Francisco Menezes, an economist and one of the authors of a progress report on the 2030 sustainable development agenda, presented recently to the UN by a group of two dozen non-government groups and research institutes, and released in full later this month.

“People are getting poorer,” said Menezes.

That was supposed to be Brazil’s past. When leftwing leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva swept to power on a wave of popular support in 2002, he promised three meals a day to all Brazilians. During his eight years of rule, and a further four by his chosen successor, Dilma Rousseff, 36 million Brazilians escaped poverty with the help of acclaimed social policies like the family allowance.

Rising commodities prices and the feverish consumer spending of a new, lower-middle class contributed to a booming economy. Those living below the poverty line fell from 25% in 2004 to 8% in 2014, when Rousseff faced re-election, according to figures from the social policy centre at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, a leading business school.

By then, though, the economy was already beginning to retract. Commodities prices fell when Rousseff secured a narrow win, with concern growing over her interventionist economic policy and soaring public spending.

By 2015, unemployment was climbing and Brazil had sunk into its deepest recession since the 1930s. The country was stripped of its investment grade. In 2016 Rousseff was impeached, ostensibly for breaking budget rules. But the process was driven by the recession and a vast corruption crisis at state-run oil company Petrobras in which many from Rousseff’s Workers’ party and its Congress allies were embroiled. By then, the number of Brazilians living in poverty had risen to an estimated 11%. “Without doubt, it is a regression,” said Marcelo Neri, director of the Vargas Foundation’s social policy centre.

Michel Temer, Rousseff’s former vice-president, took overand began cutting costs. Last December, a 20-year cap was introduced on public spending. Congress is debating reforms to Brazil’s generous pensions system. Liberal economists argue that without these reforms, Brazil will be unable to overcome its deficit and get back to growth.

The progress report argued that these austerity measures will increase poverty in Brazil and said the country should reduce other costs and adopt a fairer tax system (the highest tax rate in this deeply unequal country is 27.5%). Menezes calculated that, had the spending cap been in place in 2003, Brazil would have had 68% less to spend on social programmes between 2003 and 2015.

Meanwhile, the poor keep getting poorer. This was evident on a recent morning in a corner of Borel, a Rio favela where ramshackle wooden shacks without running water or sewage cling to a muddy hillside. Welington de Souza, a 39-year-old resident, said more homes are being built in the improvised, low-income community, where people work selling tin cans, plastic bottles and cardboard they pick off the street.

People are starting the same line of informal, cash-in-hand work, which they call “recycling”, in growing numbers. “Because of the unemployment, people are having to get by,” said De Souza, who lives with his pregnant partner Karla Santos, 19, and her son Carlos Eduardo, four, and did electrical and cleaning jobs before work dried up.

Santos’s sister, Edeane Silva, 24, lives next door with her partner Sérgio Conceição, 39, and their three young children. Their fridge has broken and water floods under the door when it rains, said Silva. Since her £101 a month family allowance was stopped, she has been “recycling” with Conceição, leaving her baby boy with her mother.

“Sometimes I think I need some meat on the table, and I don’t come home until I get it,” Conceição said. “I have to have faith.”

What Brazilians lack is faith that their politicians have any ability to resolve the mess the country is in and tackle its rising poverty. As graft scandals multiply, most are too busy trying to save themselves. Earlier this year, investigations were authorised into eight of Temer’s ministers. On 2 August, the lower house of Congress will vote on whether to authorise a trial of the president himself on corruption charges.

Temer’s centrist PMDB party has run Rio’s state government since 2007. Its former governor Sérgio Cabral is in jail, accused of pocketing substantial bribes, while the state government is broke and months in arrears with salaries. Unions have been organising food donations for hungry staff.

All of which has fed into an increasingly chaotic environment, where new legislation threatens advances in food security, as well as undermining health, education and social security services, the progress report warned.

“There is a generalised lack of confidence in relation to the political class, the justice system, and the executive and legislative powers,” said the report’s authors, adding that “the most vulnerable populations” were among “the most prejudiced”.

People are getting poorer’: hunger and homelessness as Brazil

crisis deepens. The Guardian, 2017. Disponível em: <https://www. theauardian.com/alobal-development/2017/iul/19/people-aettinapoorer-hunaer-homelessness-brazil-crisis>

For the question read the text below:

People are getting poorer’: hunger and homelessness as Brazil crisis deepens

Unemployment and social instability threaten unwelcome return to the past in recession-hit country once seen as a model for developing economies.

It wasn’t yet 5am when Miriam Gomes drove up to Happy Little Angel, the social project she runs in the scruffy Cidade Nova neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro, but the queue for her weekly food handout was already a hundred yards long.

Some had slept outside - those among Rio’s growing army of homeless people, or who lived too far away to get there by 6.30am, when those registered could start collecting a bag of vegetables, fruit, rice, beans, pasta, milk and biscuits, and a little chocolate.

These are some of the victims of a worsening problem in a country once praised for reducing poverty, but where the numbers of poor are climbing again.

Brazil has slumped into its worst recession for decades, with 14 million people unemployed.

There are a lot more people on the street,” said Gomes, 53, who bought the house where Little Happy Angel is based with an inheritance, and lives off her late father’s military pension.

Some of those Gomes helps benefit from a cash transfer scheme called the family allowance, but still struggle to make ends meet. Others are among the 1.1 million families the government removed from the programme last year for what it called “irregularities”.

Among the latter is Vera dos Santos, 43, who lost her job as a maid two and a half years ago, has three teenage children to feed, and recently had her allowance stopped. “My financial situation is difficult,” she said.

Brazil celebrated its removal from the UN hunger map in 2014. Now it is in danger, a new report warns, of being reinstated.

“If we don’t take the due providences, Brazil will go back to the hunger map,” said Francisco Menezes, an economist and one of the authors of a progress report on the 2030 sustainable development agenda, presented recently to the UN by a group of two dozen non-government groups and research institutes, and released in full later this month.

“People are getting poorer,” said Menezes.

That was supposed to be Brazil’s past. When leftwing leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva swept to power on a wave of popular support in 2002, he promised three meals a day to all Brazilians. During his eight years of rule, and a further four by his chosen successor, Dilma Rousseff, 36 million Brazilians escaped poverty with the help of acclaimed social policies like the family allowance.

Rising commodities prices and the feverish consumer spending of a new, lower-middle class contributed to a booming economy. Those living below the poverty line fell from 25% in 2004 to 8% in 2014, when Rousseff faced re-election, according to figures from the social policy centre at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, a leading business school.

By then, though, the economy was already beginning to retract. Commodities prices fell when Rousseff secured a narrow win, with concern growing over her interventionist economic policy and soaring public spending.

By 2015, unemployment was climbing and Brazil had sunk into its deepest recession since the 1930s. The country was stripped of its investment grade. In 2016 Rousseff was impeached, ostensibly for breaking budget rules. But the process was driven by the recession and a vast corruption crisis at state-run oil company Petrobras in which many from Rousseff’s Workers’ party and its Congress allies were embroiled. By then, the number of Brazilians living in poverty had risen to an estimated 11%. “Without doubt, it is a regression,” said Marcelo Neri, director of the Vargas Foundation’s social policy centre.

Michel Temer, Rousseff’s former vice-president, took overand began cutting costs. Last December, a 20-year cap was introduced on public spending. Congress is debating reforms to Brazil’s generous pensions system. Liberal economists argue that without these reforms, Brazil will be unable to overcome its deficit and get back to growth.

The progress report argued that these austerity measures will increase poverty in Brazil and said the country should reduce other costs and adopt a fairer tax system (the highest tax rate in this deeply unequal country is 27.5%). Menezes calculated that, had the spending cap been in place in 2003, Brazil would have had 68% less to spend on social programmes between 2003 and 2015.

Meanwhile, the poor keep getting poorer. This was evident on a recent morning in a corner of Borel, a Rio favela where ramshackle wooden shacks without running water or sewage cling to a muddy hillside. Welington de Souza, a 39-year-old resident, said more homes are being built in the improvised, low-income community, where people work selling tin cans, plastic bottles and cardboard they pick off the street.

People are starting the same line of informal, cash-in-hand work, which they call “recycling”, in growing numbers. “Because of the unemployment, people are having to get by,” said De Souza, who lives with his pregnant partner Karla Santos, 19, and her son Carlos Eduardo, four, and did electrical and cleaning jobs before work dried up.

Santos’s sister, Edeane Silva, 24, lives next door with her partner Sérgio Conceição, 39, and their three young children. Their fridge has broken and water floods under the door when it rains, said Silva. Since her £101 a month family allowance was stopped, she has been “recycling” with Conceição, leaving her baby boy with her mother.

“Sometimes I think I need some meat on the table, and I don’t come home until I get it,” Conceição said. “I have to have faith.”

What Brazilians lack is faith that their politicians have any ability to resolve the mess the country is in and tackle its rising poverty. As graft scandals multiply, most are too busy trying to save themselves. Earlier this year, investigations were authorised into eight of Temer’s ministers. On 2 August, the lower house of Congress will vote on whether to authorise a trial of the president himself on corruption charges.

Temer’s centrist PMDB party has run Rio’s state government since 2007. Its former governor Sérgio Cabral is in jail, accused of pocketing substantial bribes, while the state government is broke and months in arrears with salaries. Unions have been organising food donations for hungry staff.

All of which has fed into an increasingly chaotic environment, where new legislation threatens advances in food security, as well as undermining health, education and social security services, the progress report warned.

“There is a generalised lack of confidence in relation to the political class, the justice system, and the executive and legislative powers,” said the report’s authors, adding that “the most vulnerable populations” were among “the most prejudiced”.

People are getting poorer’: hunger and homelessness as Brazil

crisis deepens. The Guardian, 2017. Disponível em: <https://www. theauardian.com/alobal-development/2017/iul/19/people-aettinapoorer-hunaer-homelessness-brazil-crisis>

For the question read the text below:

People are getting poorer’: hunger and homelessness as Brazil crisis deepens

Unemployment and social instability threaten unwelcome return to the past in recession-hit country once seen as a model for developing economies.

It wasn’t yet 5am when Miriam Gomes drove up to Happy Little Angel, the social project she runs in the scruffy Cidade Nova neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro, but the queue for her weekly food handout was already a hundred yards long.

Some had slept outside - those among Rio’s growing army of homeless people, or who lived too far away to get there by 6.30am, when those registered could start collecting a bag of vegetables, fruit, rice, beans, pasta, milk and biscuits, and a little chocolate.

These are some of the victims of a worsening problem in a country once praised for reducing poverty, but where the numbers of poor are climbing again.

Brazil has slumped into its worst recession for decades, with 14 million people unemployed.

There are a lot more people on the street,” said Gomes, 53, who bought the house where Little Happy Angel is based with an inheritance, and lives off her late father’s military pension.

Some of those Gomes helps benefit from a cash transfer scheme called the family allowance, but still struggle to make ends meet. Others are among the 1.1 million families the government removed from the programme last year for what it called “irregularities”.

Among the latter is Vera dos Santos, 43, who lost her job as a maid two and a half years ago, has three teenage children to feed, and recently had her allowance stopped. “My financial situation is difficult,” she said.

Brazil celebrated its removal from the UN hunger map in 2014. Now it is in danger, a new report warns, of being reinstated.

“If we don’t take the due providences, Brazil will go back to the hunger map,” said Francisco Menezes, an economist and one of the authors of a progress report on the 2030 sustainable development agenda, presented recently to the UN by a group of two dozen non-government groups and research institutes, and released in full later this month.

“People are getting poorer,” said Menezes.

That was supposed to be Brazil’s past. When leftwing leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva swept to power on a wave of popular support in 2002, he promised three meals a day to all Brazilians. During his eight years of rule, and a further four by his chosen successor, Dilma Rousseff, 36 million Brazilians escaped poverty with the help of acclaimed social policies like the family allowance.

Rising commodities prices and the feverish consumer spending of a new, lower-middle class contributed to a booming economy. Those living below the poverty line fell from 25% in 2004 to 8% in 2014, when Rousseff faced re-election, according to figures from the social policy centre at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, a leading business school.

By then, though, the economy was already beginning to retract. Commodities prices fell when Rousseff secured a narrow win, with concern growing over her interventionist economic policy and soaring public spending.

By 2015, unemployment was climbing and Brazil had sunk into its deepest recession since the 1930s. The country was stripped of its investment grade. In 2016 Rousseff was impeached, ostensibly for breaking budget rules. But the process was driven by the recession and a vast corruption crisis at state-run oil company Petrobras in which many from Rousseff’s Workers’ party and its Congress allies were embroiled. By then, the number of Brazilians living in poverty had risen to an estimated 11%. “Without doubt, it is a regression,” said Marcelo Neri, director of the Vargas Foundation’s social policy centre.

Michel Temer, Rousseff’s former vice-president, took overand began cutting costs. Last December, a 20-year cap was introduced on public spending. Congress is debating reforms to Brazil’s generous pensions system. Liberal economists argue that without these reforms, Brazil will be unable to overcome its deficit and get back to growth.

The progress report argued that these austerity measures will increase poverty in Brazil and said the country should reduce other costs and adopt a fairer tax system (the highest tax rate in this deeply unequal country is 27.5%). Menezes calculated that, had the spending cap been in place in 2003, Brazil would have had 68% less to spend on social programmes between 2003 and 2015.

Meanwhile, the poor keep getting poorer. This was evident on a recent morning in a corner of Borel, a Rio favela where ramshackle wooden shacks without running water or sewage cling to a muddy hillside. Welington de Souza, a 39-year-old resident, said more homes are being built in the improvised, low-income community, where people work selling tin cans, plastic bottles and cardboard they pick off the street.

People are starting the same line of informal, cash-in-hand work, which they call “recycling”, in growing numbers. “Because of the unemployment, people are having to get by,” said De Souza, who lives with his pregnant partner Karla Santos, 19, and her son Carlos Eduardo, four, and did electrical and cleaning jobs before work dried up.

Santos’s sister, Edeane Silva, 24, lives next door with her partner Sérgio Conceição, 39, and their three young children. Their fridge has broken and water floods under the door when it rains, said Silva. Since her £101 a month family allowance was stopped, she has been “recycling” with Conceição, leaving her baby boy with her mother.

“Sometimes I think I need some meat on the table, and I don’t come home until I get it,” Conceição said. “I have to have faith.”

What Brazilians lack is faith that their politicians have any ability to resolve the mess the country is in and tackle its rising poverty. As graft scandals multiply, most are too busy trying to save themselves. Earlier this year, investigations were authorised into eight of Temer’s ministers. On 2 August, the lower house of Congress will vote on whether to authorise a trial of the president himself on corruption charges.

Temer’s centrist PMDB party has run Rio’s state government since 2007. Its former governor Sérgio Cabral is in jail, accused of pocketing substantial bribes, while the state government is broke and months in arrears with salaries. Unions have been organising food donations for hungry staff.

All of which has fed into an increasingly chaotic environment, where new legislation threatens advances in food security, as well as undermining health, education and social security services, the progress report warned.

“There is a generalised lack of confidence in relation to the political class, the justice system, and the executive and legislative powers,” said the report’s authors, adding that “the most vulnerable populations” were among “the most prejudiced”.

People are getting poorer’: hunger and homelessness as Brazil

crisis deepens. The Guardian, 2017. Disponível em: <https://www. theauardian.com/alobal-development/2017/iul/19/people-aettinapoorer-hunaer-homelessness-brazil-crisis>

For the question read the text below:

People are getting poorer’: hunger and homelessness as Brazil crisis deepens

Unemployment and social instability threaten unwelcome return to the past in recession-hit country once seen as a model for developing economies.

It wasn’t yet 5am when Miriam Gomes drove up to Happy Little Angel, the social project she runs in the scruffy Cidade Nova neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro, but the queue for her weekly food handout was already a hundred yards long.

Some had slept outside - those among Rio’s growing army of homeless people, or who lived too far away to get there by 6.30am, when those registered could start collecting a bag of vegetables, fruit, rice, beans, pasta, milk and biscuits, and a little chocolate.

These are some of the victims of a worsening problem in a country once praised for reducing poverty, but where the numbers of poor are climbing again.

Brazil has slumped into its worst recession for decades, with 14 million people unemployed.

There are a lot more people on the street,” said Gomes, 53, who bought the house where Little Happy Angel is based with an inheritance, and lives off her late father’s military pension.

Some of those Gomes helps benefit from a cash transfer scheme called the family allowance, but still struggle to make ends meet. Others are among the 1.1 million families the government removed from the programme last year for what it called “irregularities”.

Among the latter is Vera dos Santos, 43, who lost her job as a maid two and a half years ago, has three teenage children to feed, and recently had her allowance stopped. “My financial situation is difficult,” she said.

Brazil celebrated its removal from the UN hunger map in 2014. Now it is in danger, a new report warns, of being reinstated.

“If we don’t take the due providences, Brazil will go back to the hunger map,” said Francisco Menezes, an economist and one of the authors of a progress report on the 2030 sustainable development agenda, presented recently to the UN by a group of two dozen non-government groups and research institutes, and released in full later this month.

“People are getting poorer,” said Menezes.

That was supposed to be Brazil’s past. When leftwing leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva swept to power on a wave of popular support in 2002, he promised three meals a day to all Brazilians. During his eight years of rule, and a further four by his chosen successor, Dilma Rousseff, 36 million Brazilians escaped poverty with the help of acclaimed social policies like the family allowance.

Rising commodities prices and the feverish consumer spending of a new, lower-middle class contributed to a booming economy. Those living below the poverty line fell from 25% in 2004 to 8% in 2014, when Rousseff faced re-election, according to figures from the social policy centre at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, a leading business school.

By then, though, the economy was already beginning to retract. Commodities prices fell when Rousseff secured a narrow win, with concern growing over her interventionist economic policy and soaring public spending.

By 2015, unemployment was climbing and Brazil had sunk into its deepest recession since the 1930s. The country was stripped of its investment grade. In 2016 Rousseff was impeached, ostensibly for breaking budget rules. But the process was driven by the recession and a vast corruption crisis at state-run oil company Petrobras in which many from Rousseff’s Workers’ party and its Congress allies were embroiled. By then, the number of Brazilians living in poverty had risen to an estimated 11%. “Without doubt, it is a regression,” said Marcelo Neri, director of the Vargas Foundation’s social policy centre.

Michel Temer, Rousseff’s former vice-president, took overand began cutting costs. Last December, a 20-year cap was introduced on public spending. Congress is debating reforms to Brazil’s generous pensions system. Liberal economists argue that without these reforms, Brazil will be unable to overcome its deficit and get back to growth.

The progress report argued that these austerity measures will increase poverty in Brazil and said the country should reduce other costs and adopt a fairer tax system (the highest tax rate in this deeply unequal country is 27.5%). Menezes calculated that, had the spending cap been in place in 2003, Brazil would have had 68% less to spend on social programmes between 2003 and 2015.

Meanwhile, the poor keep getting poorer. This was evident on a recent morning in a corner of Borel, a Rio favela where ramshackle wooden shacks without running water or sewage cling to a muddy hillside. Welington de Souza, a 39-year-old resident, said more homes are being built in the improvised, low-income community, where people work selling tin cans, plastic bottles and cardboard they pick off the street.

People are starting the same line of informal, cash-in-hand work, which they call “recycling”, in growing numbers. “Because of the unemployment, people are having to get by,” said De Souza, who lives with his pregnant partner Karla Santos, 19, and her son Carlos Eduardo, four, and did electrical and cleaning jobs before work dried up.

Santos’s sister, Edeane Silva, 24, lives next door with her partner Sérgio Conceição, 39, and their three young children. Their fridge has broken and water floods under the door when it rains, said Silva. Since her £101 a month family allowance was stopped, she has been “recycling” with Conceição, leaving her baby boy with her mother.

“Sometimes I think I need some meat on the table, and I don’t come home until I get it,” Conceição said. “I have to have faith.”

What Brazilians lack is faith that their politicians have any ability to resolve the mess the country is in and tackle its rising poverty. As graft scandals multiply, most are too busy trying to save themselves. Earlier this year, investigations were authorised into eight of Temer’s ministers. On 2 August, the lower house of Congress will vote on whether to authorise a trial of the president himself on corruption charges.

Temer’s centrist PMDB party has run Rio’s state government since 2007. Its former governor Sérgio Cabral is in jail, accused of pocketing substantial bribes, while the state government is broke and months in arrears with salaries. Unions have been organising food donations for hungry staff.

All of which has fed into an increasingly chaotic environment, where new legislation threatens advances in food security, as well as undermining health, education and social security services, the progress report warned.

“There is a generalised lack of confidence in relation to the political class, the justice system, and the executive and legislative powers,” said the report’s authors, adding that “the most vulnerable populations” were among “the most prejudiced”.

People are getting poorer’: hunger and homelessness as Brazil

crisis deepens. The Guardian, 2017. Disponível em: <https://www. theauardian.com/alobal-development/2017/iul/19/people-aettinapoorer-hunaer-homelessness-brazil-crisis>

I. “Casal maduro vive os últimos capítulos de uma crise matrimonial diante dos olhos da filha mais velha, uma adolescente que está a um passo de iniciar-se na vida adulta e amorosa.” II. “Em 2017, o Papa Francisco recebeu de presente da Lamborghini uma unidade do esportivo Huracán. Trata-se de um modelo personalizado pela fabricante italiana como homenagem para o Vaticano, de quem empresta as cores da bandeira. O papa assinou o capô e resolveu colocá-lo à venda para beneficiar instituições de caridade.’’ III. “Por mais voltas que o mundo dê, um dia todos nós iremos nos encontrar em algum ponto. Um ponto pacífico, onde estaremos falando a mesma língua, bebendo o mesmo vinho, contando nossas histórias e rindo, um riso leve e sincero. Assim, estaremos prontos para percorrer juntos este longo caminho; em que simplesmente falamos de nossos dias, vendo o futuro com olhos livres.’’ Charles Chaplin IV. “Espalhe o amor por onde você for antes de tudo, em sua própria casa. Dê amor a seus filhos, sua esposa ou seu marido, a um vizinho próximo... Não permita jamais, que alguém se aproxime de você sem viver melhor, e mais feliz. Seja a expressão viva da bondade de deus; bondade em seu rosto, bondade em seus olhos, bondade em seu sorriso, bondade em sua terna saudação" Madre Teresa de Calcutá

Com base na gramática de pontuação da língua culta, assinale a alternativa correta:

Analise o poema de Rudolf Steiner:

“No coração tece o sentir

Na cabeça brilha o pensar

Nos membros vigora o querer

Brilhocente

Tecer revigorante

Vigor brilhante

Isto é o homem.

Com relação à palavra “Brilhocente”:

Assinale a alternativa correta.

( ) Renderam-se às tropas aliadas as forças germânicas de terra, mar e ar. (O núcleo do sujeito é, “forças germânicas”). ( ) Pode haver grandes shows na virada cultural. (O verbo haver tem valor existencial). ( ) Precisa-se de pedreiro. (A partícula SE atua como determinante do sujeito). ( ) Foram incentivados a comemorar a queda do governo. (O infinitivo não é flexionado, principalmente, em locuções verbais e verbos preposicionados).

Assinale a alternativa que, respectivamente, apresenta a sequência correta de cima para baixo.

Leia com atenção o fragmento do livro Mensagem, de Fernando Pessoa:

“Há em mim fenômenos de abulia que a histeria, propriamente dita, não enquadra no registo dos seus sintomas. Seja como for, a origem mental dos heterônimos está na minha tendência orgânica e constante para a despersonalização e para simulação. Estes fenômenos - felizmente para mim e para outros - mentalizaram-se em mim; quero dizer, não se manifestam na minha vida prática, exterior e de contato com os outros; fazem explosão para dentro e vivo-os eu a sós comigo. Se eu fosse mulher - na mulher os fenômenos histéricos rompem em ataques e cousas parecidas - cada poema de Álvaro de Campos (o mais histericamente histérico de mim) seria um alarme para vizinhança. Mas sou homem - e nos homens a histeria assume aspectos mentais: assim tudo acaba em silêncio e poesia...”

Assinale a alternativa incorreta:

Considere os textos:

1. “... a riqueza provoca um tipo de consumo “ostentatório”, comprando que serviam apenas para demonstrar o status dos ricos. [...] Esse consumo provoca a imitação dos pobres, que por sua vez, passavam, dentro das suas possibilidades, a consumir objetos desnecessários, mas que lhe davam aparência de “classe superior" (José Chiavenato).

2.

3. “Eu me utilizo de todos os meios da Sociedade de consumo, penetro no Sistema, mas como um veneno” (Raul Seixas)

Ao compará-los, é correto afirmar:

I. Na atualidade os bens de consumo são o equilíbrio físico e mental necessários para toda a sociedade.

II. Há um consumo ilimitado de bens, sobretudo em artigos de pouca necessidade.

III. As palavras “ostentatório” e “veneno” servem para definir o que representa o consumismo no mundo atual.

IV. O consumismo é necessário pela importância da produtividade industrial no mundo moderno a menos que ultrapasse os limites da classe menos favorecida.

Estão corretas as afirmativas:

“Os conhecimentos produzidos na área de políticas públicas vêm sendo largamente utilizado por pesquisadores, políticos e administradores que lidam com problemas públicos em diversos setores de intervenção e nas mais diferentes áreas: ciência política, sociologia, economia, administração pública, direito etc.[i] Vêm sendo utilizado tanto no que diz respeito à implementação e a avaliação das políticas públicas, quanto no que diz respeito a abordagens que destacam o papel das ideias e do conhecimento neste processo[ii].”

As palavras destacadas estão morfologicamente classificadas, respectivamente e conforme os preceitos da norma culta. A esse respeito, assinale a alternativa correta.

Observe a tirinha:

Analisando a tirinha é possível afirmar que:

I. O objetivo da linguagem utilizada não é expor verbalmente a realidade, não há a necessidade de vocábulos. II. Nos mostra que os pais da nova geração não conseguem ser exemplos ideais para os filhos. III. A importância da linguagem televisiva para os padrões atuais. IV. A relação decadente entre mídia e educação nos dias atuais.

Estão corretas as afirmativas:

Leia com atenção o poema de Gregório de Matos:

Três dúzias de casebres remendados,

Seis becos de mentrastos entupidos

Quinze soldados rotos e despidos

Doze porcos na praça bem criados.

Dois conventos, seis frades, três letrados

Um juiz com bigodes sem ouvidos

Três presos de piolhos carcomidos

Por comer dois meirinhos esfaimados.

As damas com sapatos de baeta

Palmilha de tamanca como frade

Saia de chita, cinta de raquete.

O feijão que só faz ventosidade

Farinha de pipoca, pão de greta

De Sergipe Del Rei esta é a cidade.

Quanto à tipologia textual usada pelo escritor analise

as afirmativas a seguir:

I. É uma descrição, por relatar as características de um local.

II. É uma dissertação, por analisar e interpretar dados reais sobre a cidade de Sergipe Del Rei.

III. É apenas a definição de uma linda cidade aos olhos do poeta.

IV. É uma exposição, são apresentadas informações sobre assuntos e fatos específicos; expõe ideias; explica; avalia; reflete.

Estão corretas as afirmativas:

Leia o fragmento do texto:

“Acredita-se que o ebola se propague em longas distâncias ao ser levado por morcegos, que podem hospedar o vírus sem morrer. Assim, ele infecta outros animais com os quais os mamíferos voadores compartilham árvores, como os macacos. Frequentemente se propaga para os humanos através de carne infectada. A geografia remota e extensa do Congo lhe dá uma vantagem com relação a outras zonas, já que os surtos costumam ser localizados e são relativamente fáceis de isolar.”

A partir do texto, leia as afirmativas interpretadas gramaticalmente a seguir:

I. É afirmada a indeterminação do sujeito, ao se apresentar o verbo acreditar em terceira pessoa, acompanhado do pronome SE.

II. Há a participação do sujeito composto ao lermos no texto, uma geografia remota e extensa do Congo.

III. O advérbio de modo está presente quando é classificado o modo que se propaga a doença para os seres humanos.

IV. Ao dizer ’’frequentemente”, se faz a classificação do tempo necessário para que a enfermidade acometa os seres humanos por intermédio da carne infectada.

Estão corretas as afirmativas: