Questões de Concurso Sobre inglês

Foram encontradas 17.635 questões

Ano: 2014

Banca:

CESPE / CEBRASPE

Órgão:

Câmara dos Deputados

Prova:

CESPE - 2014 - Câmara dos Deputados - Analista Legislativo - Consultor de Orçamento e Fiscalização Financeira |

Q420821

Inglês

Texto associado

According to the text above, judge the following item.

According to the text above, judge the following item.

The author points to a discontinuity in the history of financial bookkeeping from the end of the 15th century to the 18th century.

Q418808

Inglês

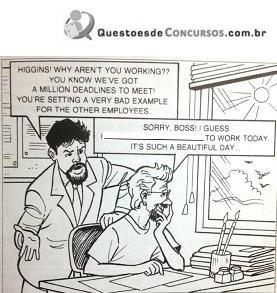

Read the dialogue in the picture. Choose the option to fill in the blank.

Q418807

Inglês

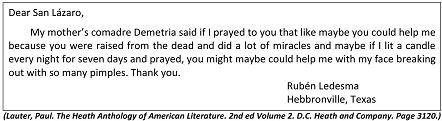

It is true about the message that

Q418806

Inglês

Texto associado

This (Illegal) American Life

By Maria E. Andreu

My parents came to New York City to make their fortune when I was a baby. Irresponsible and dreamy and in their early 20s, they didn't think things through when their visa expired; they decided to stay just a bit longer to build up a nest egg.

But our stay got progressively longer, until, when I was 6, my grandfather died in South America. My father decided my mother and I should go to the funeral and, with assurances that he would handle everything, sat me down and told me I'd have a nice visit in his boyhood home in Argentina, then be back in America in a month.

I didn't see him for two years.

We couldn't get a visa to return. My father sent us money from New Jersey, as the months of our absence stretched into years. Finally, he met someone who knew "coyotes" - people who smuggled others into the U.S. via Mexico. He paid them what they asked for, and we flew to Mexico City.

They drove us to the Mexican side of the border, and left us at a beach. Another from their operation picked us up there and drove us across as his family. We passed Disneyland on our way to the airport, where we boarded the plane to finally rejoin my father.

As a child, I had thought coming back home would be the magical end to our troubles, but in many ways it was the beginning. I chafed at the strictures of undocumented life: no social security number meant no public school (instead I attended a Catholic school my parents could scarcely afford); no driver's license, no after-school job. My parents had made their choices, and I had to live with those, seeing off my classmates as they left on a class trip to Canada, or packing to go off to college, where 1 could not go.

The year before I graduated from high school, Congress passed the amnesty law of 1987. A few months after my 18th birthday, I became legal and what had always seemed a blank future of no hope suddenly turned dazzling with possibility.

When I went for my interview at the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the caseworker looked at me quizzically when he heard me talk in unaccented English and joke about current events. Surely this American teenager did not fit in with the crowd of illegals looking to make things right.

At the time, I was flattered. His confusion meant I could pass as an American.

(Newsweek, October 2f 2008. Page 12.)

In "Finally, he met someone who knew 'coyotes' - people who smuggled others into the United States via Mexico." the relative pronouns can

Q418805

Inglês

Texto associado

This (Illegal) American Life

By Maria E. Andreu

My parents came to New York City to make their fortune when I was a baby. Irresponsible and dreamy and in their early 20s, they didn't think things through when their visa expired; they decided to stay just a bit longer to build up a nest egg.

But our stay got progressively longer, until, when I was 6, my grandfather died in South America. My father decided my mother and I should go to the funeral and, with assurances that he would handle everything, sat me down and told me I'd have a nice visit in his boyhood home in Argentina, then be back in America in a month.

I didn't see him for two years.

We couldn't get a visa to return. My father sent us money from New Jersey, as the months of our absence stretched into years. Finally, he met someone who knew "coyotes" - people who smuggled others into the U.S. via Mexico. He paid them what they asked for, and we flew to Mexico City.

They drove us to the Mexican side of the border, and left us at a beach. Another from their operation picked us up there and drove us across as his family. We passed Disneyland on our way to the airport, where we boarded the plane to finally rejoin my father.

As a child, I had thought coming back home would be the magical end to our troubles, but in many ways it was the beginning. I chafed at the strictures of undocumented life: no social security number meant no public school (instead I attended a Catholic school my parents could scarcely afford); no driver's license, no after-school job. My parents had made their choices, and I had to live with those, seeing off my classmates as they left on a class trip to Canada, or packing to go off to college, where 1 could not go.

The year before I graduated from high school, Congress passed the amnesty law of 1987. A few months after my 18th birthday, I became legal and what had always seemed a blank future of no hope suddenly turned dazzling with possibility.

When I went for my interview at the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the caseworker looked at me quizzically when he heard me talk in unaccented English and joke about current events. Surely this American teenager did not fit in with the crowd of illegals looking to make things right.

At the time, I was flattered. His confusion meant I could pass as an American.

(Newsweek, October 2f 2008. Page 12.)

In "My father decided my mother and I should go to the funeral" the modal can be replaced by

Q418804

Inglês

Texto associado

This (Illegal) American Life

By Maria E. Andreu

My parents came to New York City to make their fortune when I was a baby. Irresponsible and dreamy and in their early 20s, they didn't think things through when their visa expired; they decided to stay just a bit longer to build up a nest egg.

But our stay got progressively longer, until, when I was 6, my grandfather died in South America. My father decided my mother and I should go to the funeral and, with assurances that he would handle everything, sat me down and told me I'd have a nice visit in his boyhood home in Argentina, then be back in America in a month.

I didn't see him for two years.

We couldn't get a visa to return. My father sent us money from New Jersey, as the months of our absence stretched into years. Finally, he met someone who knew "coyotes" - people who smuggled others into the U.S. via Mexico. He paid them what they asked for, and we flew to Mexico City.

They drove us to the Mexican side of the border, and left us at a beach. Another from their operation picked us up there and drove us across as his family. We passed Disneyland on our way to the airport, where we boarded the plane to finally rejoin my father.

As a child, I had thought coming back home would be the magical end to our troubles, but in many ways it was the beginning. I chafed at the strictures of undocumented life: no social security number meant no public school (instead I attended a Catholic school my parents could scarcely afford); no driver's license, no after-school job. My parents had made their choices, and I had to live with those, seeing off my classmates as they left on a class trip to Canada, or packing to go off to college, where 1 could not go.

The year before I graduated from high school, Congress passed the amnesty law of 1987. A few months after my 18th birthday, I became legal and what had always seemed a blank future of no hope suddenly turned dazzling with possibility.

When I went for my interview at the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the caseworker looked at me quizzically when he heard me talk in unaccented English and joke about current events. Surely this American teenager did not fit in with the crowd of illegals looking to make things right.

At the time, I was flattered. His confusion meant I could pass as an American.

(Newsweek, October 2f 2008. Page 12.)

In "They decided to stay a bit longer to build up a nest egg" NESTEGG is a/an

Q418803

Inglês

Texto associado

This (Illegal) American Life

By Maria E. Andreu

My parents came to New York City to make their fortune when I was a baby. Irresponsible and dreamy and in their early 20s, they didn't think things through when their visa expired; they decided to stay just a bit longer to build up a nest egg.

But our stay got progressively longer, until, when I was 6, my grandfather died in South America. My father decided my mother and I should go to the funeral and, with assurances that he would handle everything, sat me down and told me I'd have a nice visit in his boyhood home in Argentina, then be back in America in a month.

I didn't see him for two years.

We couldn't get a visa to return. My father sent us money from New Jersey, as the months of our absence stretched into years. Finally, he met someone who knew "coyotes" - people who smuggled others into the U.S. via Mexico. He paid them what they asked for, and we flew to Mexico City.

They drove us to the Mexican side of the border, and left us at a beach. Another from their operation picked us up there and drove us across as his family. We passed Disneyland on our way to the airport, where we boarded the plane to finally rejoin my father.

As a child, I had thought coming back home would be the magical end to our troubles, but in many ways it was the beginning. I chafed at the strictures of undocumented life: no social security number meant no public school (instead I attended a Catholic school my parents could scarcely afford); no driver's license, no after-school job. My parents had made their choices, and I had to live with those, seeing off my classmates as they left on a class trip to Canada, or packing to go off to college, where 1 could not go.

The year before I graduated from high school, Congress passed the amnesty law of 1987. A few months after my 18th birthday, I became legal and what had always seemed a blank future of no hope suddenly turned dazzling with possibility.

When I went for my interview at the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the caseworker looked at me quizzically when he heard me talk in unaccented English and joke about current events. Surely this American teenager did not fit in with the crowd of illegals looking to make things right.

At the time, I was flattered. His confusion meant I could pass as an American.

(Newsweek, October 2f 2008. Page 12.)

I n "I was flattered. His confusion meant I could pass as an American." FLATTERED is

Q418802

Inglês

Texto associado

This (Illegal) American Life

By Maria E. Andreu

My parents came to New York City to make their fortune when I was a baby. Irresponsible and dreamy and in their early 20s, they didn't think things through when their visa expired; they decided to stay just a bit longer to build up a nest egg.

But our stay got progressively longer, until, when I was 6, my grandfather died in South America. My father decided my mother and I should go to the funeral and, with assurances that he would handle everything, sat me down and told me I'd have a nice visit in his boyhood home in Argentina, then be back in America in a month.

I didn't see him for two years.

We couldn't get a visa to return. My father sent us money from New Jersey, as the months of our absence stretched into years. Finally, he met someone who knew "coyotes" - people who smuggled others into the U.S. via Mexico. He paid them what they asked for, and we flew to Mexico City.

They drove us to the Mexican side of the border, and left us at a beach. Another from their operation picked us up there and drove us across as his family. We passed Disneyland on our way to the airport, where we boarded the plane to finally rejoin my father.

As a child, I had thought coming back home would be the magical end to our troubles, but in many ways it was the beginning. I chafed at the strictures of undocumented life: no social security number meant no public school (instead I attended a Catholic school my parents could scarcely afford); no driver's license, no after-school job. My parents had made their choices, and I had to live with those, seeing off my classmates as they left on a class trip to Canada, or packing to go off to college, where 1 could not go.

The year before I graduated from high school, Congress passed the amnesty law of 1987. A few months after my 18th birthday, I became legal and what had always seemed a blank future of no hope suddenly turned dazzling with possibility.

When I went for my interview at the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the caseworker looked at me quizzically when he heard me talk in unaccented English and joke about current events. Surely this American teenager did not fit in with the crowd of illegals looking to make things right.

At the time, I was flattered. His confusion meant I could pass as an American.

(Newsweek, October 2f 2008. Page 12.)

Some of the author's hassles were

Q418801

Inglês

Texto associado

This (Illegal) American Life

By Maria E. Andreu

My parents came to New York City to make their fortune when I was a baby. Irresponsible and dreamy and in their early 20s, they didn't think things through when their visa expired; they decided to stay just a bit longer to build up a nest egg.

But our stay got progressively longer, until, when I was 6, my grandfather died in South America. My father decided my mother and I should go to the funeral and, with assurances that he would handle everything, sat me down and told me I'd have a nice visit in his boyhood home in Argentina, then be back in America in a month.

I didn't see him for two years.

We couldn't get a visa to return. My father sent us money from New Jersey, as the months of our absence stretched into years. Finally, he met someone who knew "coyotes" - people who smuggled others into the U.S. via Mexico. He paid them what they asked for, and we flew to Mexico City.

They drove us to the Mexican side of the border, and left us at a beach. Another from their operation picked us up there and drove us across as his family. We passed Disneyland on our way to the airport, where we boarded the plane to finally rejoin my father.

As a child, I had thought coming back home would be the magical end to our troubles, but in many ways it was the beginning. I chafed at the strictures of undocumented life: no social security number meant no public school (instead I attended a Catholic school my parents could scarcely afford); no driver's license, no after-school job. My parents had made their choices, and I had to live with those, seeing off my classmates as they left on a class trip to Canada, or packing to go off to college, where 1 could not go.

The year before I graduated from high school, Congress passed the amnesty law of 1987. A few months after my 18th birthday, I became legal and what had always seemed a blank future of no hope suddenly turned dazzling with possibility.

When I went for my interview at the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the caseworker looked at me quizzically when he heard me talk in unaccented English and joke about current events. Surely this American teenager did not fit in with the crowd of illegals looking to make things right.

At the time, I was flattered. His confusion meant I could pass as an American.

(Newsweek, October 2f 2008. Page 12.)

The author and her mother

Q418800

Inglês

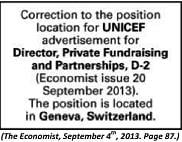

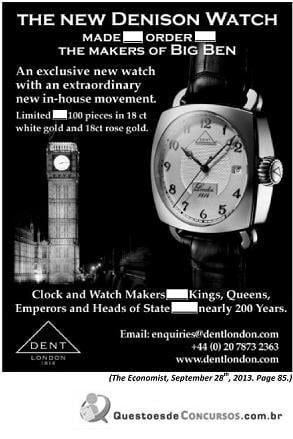

The ad contains a/an

Q418799

Inglês

Choose the sequence to fill in the blanks

Ano: 2014

Banca:

FUNIVERSA

Órgão:

SEAP-DF

Prova:

FUNIVERSA - 2014 - SEAP-DF - Auditor de Controle Interno - Planejamento e Orçamento |

Q418461

Inglês

Among the words listed below, the only one which forms the plural by adding an “s” is

Ano: 2014

Banca:

FUNIVERSA

Órgão:

SEAP-DF

Prova:

FUNIVERSA - 2014 - SEAP-DF - Auditor de Controle Interno - Planejamento e Orçamento |

Q418460

Inglês

None of the companies surveyed in these countries indicated plans to reduce staff.

Ano: 2014

Banca:

FUNIVERSA

Órgão:

SEAP-DF

Prova:

FUNIVERSA - 2014 - SEAP-DF - Auditor de Controle Interno - Planejamento e Orçamento |

Q418459

Inglês

Robert Half Singapore is a

Ano: 2014

Banca:

FUNIVERSA

Órgão:

SEAP-DF

Prova:

FUNIVERSA - 2014 - SEAP-DF - Auditor de Controle Interno - Planejamento e Orçamento |

Q418458

Inglês

In Singapore, the future for accounting and finance professionals looks

Ano: 2014

Banca:

FUNIVERSA

Órgão:

SEAP-DF

Prova:

FUNIVERSA - 2014 - SEAP-DF - Auditor de Controle Interno - Planejamento e Orçamento |

Q418457

Inglês

Choose the right alternative to complete the sentence below.

Brazil is the _________ most active hiring market for accounting and finance professionals.

Brazil is the _________ most active hiring market for accounting and finance professionals.

Ano: 2014

Banca:

FUNIVERSA

Órgão:

SEAP-DF

Prova:

FUNIVERSA - 2014 - SEAP-DF - Auditor de Controle Interno - Finanças e Controle |

Q418212

Inglês

Someone whose job is to prepare financial records for a company or person is a(n)

Ano: 2014

Banca:

FUNIVERSA

Órgão:

SEAP-DF

Prova:

FUNIVERSA - 2014 - SEAP-DF - Auditor de Controle Interno - Finanças e Controle |

Q418211

Inglês

Using the above text as reference, choose the correct alternative.

An internal audit,

An internal audit,

Ano: 2014

Banca:

FUNIVERSA

Órgão:

SEAP-DF

Prova:

FUNIVERSA - 2014 - SEAP-DF - Auditor de Controle Interno - Finanças e Controle |

Q418210

Inglês

Disciplinary action may be imposed if an employee

Ano: 2014

Banca:

FUNIVERSA

Órgão:

SEAP-DF

Prova:

FUNIVERSA - 2014 - SEAP-DF - Auditor de Controle Interno - Finanças e Controle |

Q418209

Inglês

The word or phrase whose definition is “the buildings and land that a business or organization uses” is the