Questões de Concurso Público Receita Federal 2023 para Auditor-Fiscal (manhã)

Foram encontradas 80 questões

A origem dos tributos

Atualmente a atividade tributária tem assumido o papel de prover os recursos destinados ao governo para a realização dos fins almejados e revertidos para o bem-estar da coletividade, porém nem sempre foi assim.

Na antiguidade a tributação se destinava basicamente a custear guerras e a prover o sustento de uma classe governante que excedia em seus gastos com luxo e obras suntuosas para o seu mero deleite.

Em comunidades primitivas, quando a terra passou a ser um bem de muito valor e objeto constante de disputa entre diversas tribos, as tribos vencedoras exigiam vantagens tributárias tais como, contribuições em ouro, escravos e mercadorias a título de despojos de Guerra.

Na Pérsia no governo de Ciro, no século VI a. C foi implantado um eficiente sistema de correio que permitia o acompanhamento da arrecadação e controle. Tem origem na Pérsia a mais antiga taxa de prestação de serviço público, referente à expedição de carta de correspondência.

Nos antigos impérios a população pagava a “décima”, que correspondia a 10% sobre a produção devida ao Estado para as obras públicas.

No Egito antigo o império instituiu uma administração altamente especializada e centralizada e dentre as carreiras públicas, a de escriba real que controlavam a arrecadação de tributos, estava no topo da carreira. O regime tributário no Egito incidia sobre os camponeses que tinham a obrigação de pagarem a título de imposto uma contribuição sobre o montante da produção.

Na Grécia antiga os tributos serviam para custear as despesas de guerra e para isso o Estado cobrava impostos sobre estrangeiros, assim como a conquista de novas áreas servia para aumentar o controle da arrecadação tributária naquela região.

No império Romano a arrecadação de impostos também teve grande importância, pois sua riqueza e expansão foram conquistadas sobre bases tributárias. A expansão do império Romano resultou na anexação de territórios fora da Itália, sendo que as cidades provinciais pagavam os tributos diretos e permanentes sobre as pessoas, e sobre a produção da terra, bem como sobre exploração das minas. O atual sistema de múltiplos impostos foi herdado dos romanos.

(Alessandro Leôncio Frazão)

Um texto obedece a uma determinada estruturação, que, segundo seu autor, é mais conveniente.

Assinale a observação adequada sobre a estruturação desse texto.

“Os tributos são tão antigos quanto a própria humanidade, sua origem não pode ser definida com exatidão, mas acompanha a própria evolução humana, desde épocas pré-históricas quando o homem passou a fixar-se em apenas um local para caça e guarda de alimentos, sendo, portanto, dono daquele pedaço de terra. No início os tributos eram ofertas voluntárias dos homens como forma de presentear ou homenagear seus Deuses e Líderes.

Com o passar do tempo, pelo que se pode ver, as disputas por terras por meio de centenas de guerras foram responsáveis pela evolução da humanidade com o surgimento de grandes civilizações. A partir dessa época os tributos passaram a ser obrigatórios e exigidos pelos reis para financiar seus exércitos e com isso conquistar mais terras.”

(Ederson Leandro Pereira Farias)

O texto acima mostra a opinião e as informações do autor do texto sobre alguns temas ligados aos tributos.

Sobre a estruturação envolvendo informações e opiniões, assinale a opção adequada.

Num artigo sobre tributos, aparece o seguinte segmento:

“No Brasil, a história dos tributos divide-se em três momentos sendo: colonial, imperial e republicano, respectivamente nessa ordem. Os tributos existem desde o descobrimento de nossa terra, quando boa parte da exploração nativa era enviada para Portugal, época conhecida como Brasil-Colônia. O ‘Quinto do pau-brasil’ é considerado o primeiro tributo brasileiro e decorreu da exploração da árvore nativa pau-brasil (SANTOS 2015). A partir de então, os tributos foram sendo implementados e moldados até chegarmos aos dias atuais.”

Sobre a organização linguística desse segmento, assinale a observação adequada.

“A sonegação é muito antiga no Brasil e até já criou expressões na língua popular brasileira que muitos nem se dão conta de que surgiram por conta dos tributos, como o ‘Quinto dos Infernos’ que se referia à quinta parte ou os 20% que os demais países deveriam pagar para Portugal quando compravam produtos do Brasil na época da colônia. Ou ainda o ‘Santo do Pau Oco’ que eram as imagens de santos feitas em madeira ‘oca’ pois no interior delas os garimpeiros saíam com ouro dos garimpos sem pagar os tributos.”

Sobre a construção desse parágrafo, assinale a observação inadequada.

(A História do Imposto de Renda – Cristóvão Barcellos da Nóbrega)

Observe os dois primeiros períodos desse texto:

“O surgimento do imposto de renda ocorreu relativamente tarde no desenvolvimento dos povos. / A instituição de um real imposto sobre a renda exige um modelo econômico que possa ser avaliado e monitorado, para possibilitar o controle, a fiscalização e a cobrança do tributo.”

A relação lógica entre esses períodos pode ser explicada adequadamente do seguinte modo:

“Por ocasião do octogésimo aniversário do imposto de renda no Brasil, a Receita Federal editou um livro sobre a trajetória desse imposto e criou, na sua página na internet, um sítio com a Memória da Receita Federal, contando não só a evolução do imposto de renda como relevantes temas da história tributária brasileira.”

Assinale a opção que mostra informações corretas sobre o gênero e o tipo textuais desse fragmento textual.

Nesse caso, assinale a opção em que a preposição “a” tem seu papel textual corretamente identificado

- Pagaram o imposto no prazo. - Pagou-se o imposto no prazo. - Alguém pagou o imposto no prazo.

Sobre essa estruturação, assinale a afirmação correta.

Sabemos todos que a repetição de palavras idênticas num texto é um problema sempre corrigido pelos professores de redação.

Assinale a frase abaixo em que a repetição de palavras idênticas não é identificada como um problema de escrita.

Adding ethics to public finance

Evolutionary moral psychologists point the way to garnering broader support for fiscal policies

Policy decisions on taxation and public expenditures intrinsically reflect moral choices. How much of your hard-earned money is it fair for the state to collect through taxes? Should the rich pay more? Should the state provide basic public services such as education and health care for free to all citizens? And so on.

Economists and public finance practitioners have traditionally focused on economic efficiency. When considering distributional issues, they have generally steered clear of moral considerations, perhaps fearing these could be seen as subjective. However, recent work by evolutionary moral psychologists suggests that policies can be better designed and muster broader support if policymakers consider the full range of moral perspectives on public finance. A few pioneering empirical applications of this approach in the field of economics have shown promise.

For the most part, economists have customarily analyzed redistribution in a way that requires users to provide their own preferences with regard to inequality: Tell economists how much you care about inequality, and they can tell you how much redistribution is appropriate through the tax and benefit system. People (or families or households) have usually been considered as individuals, and the only relevant characteristics for these exercises have been their incomes, wealth, or spending potential.

There are two — understandable but not fully satisfactory — reasons for this approach. First, economists often wish to be viewed as objective social scientists. Second, most public finance scholars have been educated in a tradition steeped in values of societies that are WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic). In this context, individuals are at the center of the analysis, and morality is fundamentally about the golden rule — treat other people the way that you would want them to treat you, regardless of who those people are. These are crucial but ultimately insufficient perspectives on how humans make moral choices.

Evolutionary moral psychologists during the past couple of decades have shown that, faced with a moral dilemma, humans decide quickly what seems right or wrong based on instinct and later justify their decision through more deliberate reasoning. Based on evidence presented by these researchers, our instincts in the moral domain evolved as a way of fostering cooperation within a group, to help ensure survival. This modern perspective harks back to two moral philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment — David Hume and Adam Smith — who noted that sentiments are integral to people’s views on right and wrong. But most later philosophers in the Western tradition sought to base morality on reason alone.

Moral psychologists have recently shown that many people draw on moral perspectives that go well beyond the golden rule. Community, authority, divinity, purity, loyalty, and sanctity are important considerations not only in many non-Western countries, but also among politically influential segments of the population in advanced economies, as emphasized by proponents of moral foundations theory.

Regardless of whether one agrees with those broader moral perspectives, familiarity with them makes it easier to understand the underlying motivations for various groups’ positions in debates on public policies. Such understanding may help in the design of policies that can muster support from a wide range of groups with differing moral values.

Adapted from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2022/03/Addingethics-to-public-finance-Mauro

Based on the text, mark the statements below as TRUE (T) or FALSE (F).

I. The planning of fiscal strategies is impervious to moral considerations.

II. Traditional public finance education based on the golden rule is wanting as regards moral choices.

III. Since the 18th century, philosophers have been on the same page as regards moral dilemmas.

The statements are, respectively,

Adding ethics to public finance

Evolutionary moral psychologists point the way to garnering broader support for fiscal policies

Policy decisions on taxation and public expenditures intrinsically reflect moral choices. How much of your hard-earned money is it fair for the state to collect through taxes? Should the rich pay more? Should the state provide basic public services such as education and health care for free to all citizens? And so on.

Economists and public finance practitioners have traditionally focused on economic efficiency. When considering distributional issues, they have generally steered clear of moral considerations, perhaps fearing these could be seen as subjective. However, recent work by evolutionary moral psychologists suggests that policies can be better designed and muster broader support if policymakers consider the full range of moral perspectives on public finance. A few pioneering empirical applications of this approach in the field of economics have shown promise.

For the most part, economists have customarily analyzed redistribution in a way that requires users to provide their own preferences with regard to inequality: Tell economists how much you care about inequality, and they can tell you how much redistribution is appropriate through the tax and benefit system. People (or families or households) have usually been considered as individuals, and the only relevant characteristics for these exercises have been their incomes, wealth, or spending potential.

There are two — understandable but not fully satisfactory — reasons for this approach. First, economists often wish to be viewed as objective social scientists. Second, most public finance scholars have been educated in a tradition steeped in values of societies that are WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic). In this context, individuals are at the center of the analysis, and morality is fundamentally about the golden rule — treat other people the way that you would want them to treat you, regardless of who those people are. These are crucial but ultimately insufficient perspectives on how humans make moral choices.

Evolutionary moral psychologists during the past couple of decades have shown that, faced with a moral dilemma, humans decide quickly what seems right or wrong based on instinct and later justify their decision through more deliberate reasoning. Based on evidence presented by these researchers, our instincts in the moral domain evolved as a way of fostering cooperation within a group, to help ensure survival. This modern perspective harks back to two moral philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment — David Hume and Adam Smith — who noted that sentiments are integral to people’s views on right and wrong. But most later philosophers in the Western tradition sought to base morality on reason alone.

Moral psychologists have recently shown that many people draw on moral perspectives that go well beyond the golden rule. Community, authority, divinity, purity, loyalty, and sanctity are important considerations not only in many non-Western countries, but also among politically influential segments of the population in advanced economies, as emphasized by proponents of moral foundations theory.

Regardless of whether one agrees with those broader moral perspectives, familiarity with them makes it easier to understand the underlying motivations for various groups’ positions in debates on public policies. Such understanding may help in the design of policies that can muster support from a wide range of groups with differing moral values.

Adapted from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2022/03/Addingethics-to-public-finance-Mauro

Adding ethics to public finance

Evolutionary moral psychologists point the way to garnering broader support for fiscal policies

Policy decisions on taxation and public expenditures intrinsically reflect moral choices. How much of your hard-earned money is it fair for the state to collect through taxes? Should the rich pay more? Should the state provide basic public services such as education and health care for free to all citizens? And so on.

Economists and public finance practitioners have traditionally focused on economic efficiency. When considering distributional issues, they have generally steered clear of moral considerations, perhaps fearing these could be seen as subjective. However, recent work by evolutionary moral psychologists suggests that policies can be better designed and muster broader support if policymakers consider the full range of moral perspectives on public finance. A few pioneering empirical applications of this approach in the field of economics have shown promise.

For the most part, economists have customarily analyzed redistribution in a way that requires users to provide their own preferences with regard to inequality: Tell economists how much you care about inequality, and they can tell you how much redistribution is appropriate through the tax and benefit system. People (or families or households) have usually been considered as individuals, and the only relevant characteristics for these exercises have been their incomes, wealth, or spending potential.

There are two — understandable but not fully satisfactory — reasons for this approach. First, economists often wish to be viewed as objective social scientists. Second, most public finance scholars have been educated in a tradition steeped in values of societies that are WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic). In this context, individuals are at the center of the analysis, and morality is fundamentally about the golden rule — treat other people the way that you would want them to treat you, regardless of who those people are. These are crucial but ultimately insufficient perspectives on how humans make moral choices.

Evolutionary moral psychologists during the past couple of decades have shown that, faced with a moral dilemma, humans decide quickly what seems right or wrong based on instinct and later justify their decision through more deliberate reasoning. Based on evidence presented by these researchers, our instincts in the moral domain evolved as a way of fostering cooperation within a group, to help ensure survival. This modern perspective harks back to two moral philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment — David Hume and Adam Smith — who noted that sentiments are integral to people’s views on right and wrong. But most later philosophers in the Western tradition sought to base morality on reason alone.

Moral psychologists have recently shown that many people draw on moral perspectives that go well beyond the golden rule. Community, authority, divinity, purity, loyalty, and sanctity are important considerations not only in many non-Western countries, but also among politically influential segments of the population in advanced economies, as emphasized by proponents of moral foundations theory.

Regardless of whether one agrees with those broader moral perspectives, familiarity with them makes it easier to understand the underlying motivations for various groups’ positions in debates on public policies. Such understanding may help in the design of policies that can muster support from a wide range of groups with differing moral values.

Adapted from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2022/03/Addingethics-to-public-finance-Mauro

Adding ethics to public finance

Evolutionary moral psychologists point the way to garnering broader support for fiscal policies

Policy decisions on taxation and public expenditures intrinsically reflect moral choices. How much of your hard-earned money is it fair for the state to collect through taxes? Should the rich pay more? Should the state provide basic public services such as education and health care for free to all citizens? And so on.

Economists and public finance practitioners have traditionally focused on economic efficiency. When considering distributional issues, they have generally steered clear of moral considerations, perhaps fearing these could be seen as subjective. However, recent work by evolutionary moral psychologists suggests that policies can be better designed and muster broader support if policymakers consider the full range of moral perspectives on public finance. A few pioneering empirical applications of this approach in the field of economics have shown promise.

For the most part, economists have customarily analyzed redistribution in a way that requires users to provide their own preferences with regard to inequality: Tell economists how much you care about inequality, and they can tell you how much redistribution is appropriate through the tax and benefit system. People (or families or households) have usually been considered as individuals, and the only relevant characteristics for these exercises have been their incomes, wealth, or spending potential.

There are two — understandable but not fully satisfactory — reasons for this approach. First, economists often wish to be viewed as objective social scientists. Second, most public finance scholars have been educated in a tradition steeped in values of societies that are WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic). In this context, individuals are at the center of the analysis, and morality is fundamentally about the golden rule — treat other people the way that you would want them to treat you, regardless of who those people are. These are crucial but ultimately insufficient perspectives on how humans make moral choices.

Evolutionary moral psychologists during the past couple of decades have shown that, faced with a moral dilemma, humans decide quickly what seems right or wrong based on instinct and later justify their decision through more deliberate reasoning. Based on evidence presented by these researchers, our instincts in the moral domain evolved as a way of fostering cooperation within a group, to help ensure survival. This modern perspective harks back to two moral philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment — David Hume and Adam Smith — who noted that sentiments are integral to people’s views on right and wrong. But most later philosophers in the Western tradition sought to base morality on reason alone.

Moral psychologists have recently shown that many people draw on moral perspectives that go well beyond the golden rule. Community, authority, divinity, purity, loyalty, and sanctity are important considerations not only in many non-Western countries, but also among politically influential segments of the population in advanced economies, as emphasized by proponents of moral foundations theory.

Regardless of whether one agrees with those broader moral perspectives, familiarity with them makes it easier to understand the underlying motivations for various groups’ positions in debates on public policies. Such understanding may help in the design of policies that can muster support from a wide range of groups with differing moral values.

Adapted from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2022/03/Addingethics-to-public-finance-Mauro

Adding ethics to public finance

Evolutionary moral psychologists point the way to garnering broader support for fiscal policies

Policy decisions on taxation and public expenditures intrinsically reflect moral choices. How much of your hard-earned money is it fair for the state to collect through taxes? Should the rich pay more? Should the state provide basic public services such as education and health care for free to all citizens? And so on.

Economists and public finance practitioners have traditionally focused on economic efficiency. When considering distributional issues, they have generally steered clear of moral considerations, perhaps fearing these could be seen as subjective. However, recent work by evolutionary moral psychologists suggests that policies can be better designed and muster broader support if policymakers consider the full range of moral perspectives on public finance. A few pioneering empirical applications of this approach in the field of economics have shown promise.

For the most part, economists have customarily analyzed redistribution in a way that requires users to provide their own preferences with regard to inequality: Tell economists how much you care about inequality, and they can tell you how much redistribution is appropriate through the tax and benefit system. People (or families or households) have usually been considered as individuals, and the only relevant characteristics for these exercises have been their incomes, wealth, or spending potential.

There are two — understandable but not fully satisfactory — reasons for this approach. First, economists often wish to be viewed as objective social scientists. Second, most public finance scholars have been educated in a tradition steeped in values of societies that are WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic). In this context, individuals are at the center of the analysis, and morality is fundamentally about the golden rule — treat other people the way that you would want them to treat you, regardless of who those people are. These are crucial but ultimately insufficient perspectives on how humans make moral choices.

Evolutionary moral psychologists during the past couple of decades have shown that, faced with a moral dilemma, humans decide quickly what seems right or wrong based on instinct and later justify their decision through more deliberate reasoning. Based on evidence presented by these researchers, our instincts in the moral domain evolved as a way of fostering cooperation within a group, to help ensure survival. This modern perspective harks back to two moral philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment — David Hume and Adam Smith — who noted that sentiments are integral to people’s views on right and wrong. But most later philosophers in the Western tradition sought to base morality on reason alone.

Moral psychologists have recently shown that many people draw on moral perspectives that go well beyond the golden rule. Community, authority, divinity, purity, loyalty, and sanctity are important considerations not only in many non-Western countries, but also among politically influential segments of the population in advanced economies, as emphasized by proponents of moral foundations theory.

Regardless of whether one agrees with those broader moral perspectives, familiarity with them makes it easier to understand the underlying motivations for various groups’ positions in debates on public policies. Such understanding may help in the design of policies that can muster support from a wide range of groups with differing moral values.

Adapted from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2022/03/Addingethics-to-public-finance-Mauro

How trade can become a gateway to climate resilience

Most people don't think about climate change when they lift a café latte to their lips or nibble on a square of chocolate — but this could soon change.

Based on current trajectories, around a quarter of Brazil’s coffee farms and 37% of Indonesia’s are likely to be lost to climate change. Swathes of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire — where most of the world’s chocolate is sourced — will become too hot to grow cocoa by 2050.

Climate-related droughts and deadly heatwaves across the world have coincided with severe storms, cyclones, hurricanes, and, of course, a pandemic. As a consequence of these shocks, millions of people have been left without homes, and a growing number of people now face starvation and a total collapse of livelihoods as growing and exporting staple crops becomes untenable.

We must immediately rethink the shape of our economies, agricultural systems and consumption patterns. Our priority is to manufacture climate resilience in global economies and societies — and we must do it quickly.

Trade can kickstart the emergence of climate-resilient economies, especially in the poorest countries. Trade has a multiplier effect on economies by driving production growth and fostering the expansion of export industries. By shifting focus to production and exports that increase climate resilience, there is potential to exponentially increase the land surface and trade processes prepared to withstand the climate crisis.

Adapted from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/07/trade-can-be-agateway-to-climate-resilience

How trade can become a gateway to climate resilience

Most people don't think about climate change when they lift a café latte to their lips or nibble on a square of chocolate — but this could soon change.

Based on current trajectories, around a quarter of Brazil’s coffee farms and 37% of Indonesia’s are likely to be lost to climate change. Swathes of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire — where most of the world’s chocolate is sourced — will become too hot to grow cocoa by 2050.

Climate-related droughts and deadly heatwaves across the world have coincided with severe storms, cyclones, hurricanes, and, of course, a pandemic. As a consequence of these shocks, millions of people have been left without homes, and a growing number of people now face starvation and a total collapse of livelihoods as growing and exporting staple crops becomes untenable.

We must immediately rethink the shape of our economies, agricultural systems and consumption patterns. Our priority is to manufacture climate resilience in global economies and societies — and we must do it quickly.

Trade can kickstart the emergence of climate-resilient economies, especially in the poorest countries. Trade has a multiplier effect on economies by driving production growth and fostering the expansion of export industries. By shifting focus to production and exports that increase climate resilience, there is potential to exponentially increase the land surface and trade processes prepared to withstand the climate crisis.

Adapted from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/07/trade-can-be-agateway-to-climate-resilience

How trade can become a gateway to climate resilience

Most people don't think about climate change when they lift a café latte to their lips or nibble on a square of chocolate — but this could soon change.

Based on current trajectories, around a quarter of Brazil’s coffee farms and 37% of Indonesia’s are likely to be lost to climate change. Swathes of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire — where most of the world’s chocolate is sourced — will become too hot to grow cocoa by 2050.

Climate-related droughts and deadly heatwaves across the world have coincided with severe storms, cyclones, hurricanes, and, of course, a pandemic. As a consequence of these shocks, millions of people have been left without homes, and a growing number of people now face starvation and a total collapse of livelihoods as growing and exporting staple crops becomes untenable.

We must immediately rethink the shape of our economies, agricultural systems and consumption patterns. Our priority is to manufacture climate resilience in global economies and societies — and we must do it quickly.

Trade can kickstart the emergence of climate-resilient economies, especially in the poorest countries. Trade has a multiplier effect on economies by driving production growth and fostering the expansion of export industries. By shifting focus to production and exports that increase climate resilience, there is potential to exponentially increase the land surface and trade processes prepared to withstand the climate crisis.

Adapted from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/07/trade-can-be-agateway-to-climate-resilience

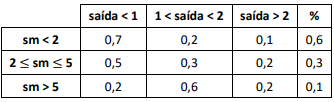

A fração dessa população que sai para jantar menos de uma vez por semana situa-se entre

A Mega-Sena é um jogo de apostas no qual são sorteadas 6 dentre 60 bolas numeradas de 1 a 60. Cecília fez uma aposta, escolhendo os números 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 e 6. Cecília está acompanhando o sorteio e viu que as três primeiras bolas sorteadas foram as de número 1, 2 e 3.

A chance de Cecília acertar os seis números e ganhar na MegaSena é agora de uma em