Questões Militares

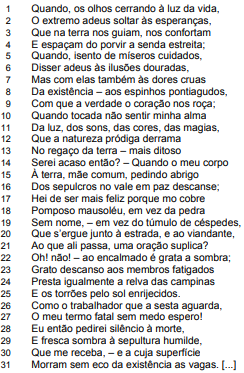

Para letras

Foram encontradas 19.010 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

Eu, desarmado e só, buscar-te venho. Tanto espero de ti. E enquanto as armas Dão lugar à razão, senhor, vejamos Se se pode salvar a vida e o sangue De tantos desgraçados. Muito tempo Pode ainda tardar-nos o recurso Com o largo oceano de permeio, Em que os suspiros dos vexados povos Perdem o alento. O dilatar-se a entrega Está nas nossas mãos, até que um dia Informados os reis nos restituam A doce antiga paz. Se o rei de Espanha Ao teu rei quer dar terras com mão larga Que lhe dê Buenos Aires, e Correntes E outras, que tem por estes vastos climas; Porém não pode dar-lhes os nossos povos.

(Disponível em: http://objdigital.bn.br/Acervo_Digital/livros_eletronicos/uraguai.pdf.)

A respeito desse poema, considere as seguintes afirmativas:

1. Atendendo as regras de composição da epopeia clássica, Basílio da Gama inspirou-se num fato histórico acontecido séculos antes da escrita e narrou-o em versos metrificados e rimados.

2. Em vez de dar voz a um pastor, como é frequente na poesia do Arcadismo, o poeta deu voz a líderes militares portugueses e aos indígenas que habitavam a região dos Sete Povos das Missões.

3. Como elementos de nativismo, aparecem as personagens Cacambo, guerreiro capaz de argumentar sobre o direito dos povos indígenas à terra, e a feiticeira Tanajura, que representa o aspecto mítico da cultura desses povos.

4. Abalada pela morte de Cacambo e auxiliada por Tanajura, Lindoia tem um sonho no qual vê com detalhes a destruição dos Sete Povos das Missões, em consequência da expulsão dos jesuítas do Brasil.

Assinale a alternativa correta.

(DIAS, Gonçalves. Poesia e prosa completas: volume único. Org.: Alexei Bueno. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Aguillar, 1998. p. 491-2.)

O auto de Natal pernambucano Morte e Vida Severina, de João Cabral de Melo Neto, apresenta algumas semelhanças temáticas com a estrofe acima transcrita, parte integrante do livro Últimos Cantos. Assinale a alternativa em que estão corretas as aproximações entre as duas obras.

1. A autora não concorda com o político russo, Lênin, acerca da avaliação que ele fez a respeito da violência do século XX.

2. Segundo Arendt, existe um fator relativo à belicosidade e à violência na atualidade que não foi considerado pelo político russo.

3. Há, no jogo de poder das superpotências, um objetivo político cuja racionalidade é a corrida armamentista e a busca da superioridade majoritária.

Assinale a alternativa correta.

1. O sujeito de “forçando o distanciamento compulsório das redes sociais” (linha 2) é “A “queda do zap” na última segunda-feira (04/10) atinou com desaviso a inquietante e cada vez mais esquecida forma de viver” (linha 1).

2. O “interessante experimento social” (linhas 4-5) refere-se às pessoas que foram levadas a “perceberem a existência do próprio real desnudo da celeridade virtual que encobre” (linha 5).

3. “A queda do zap” pode permitir a observação da relação entre a transformação do tempo-livre dos indivíduos em valor de troca e a valorização do capital com desdobramentos financeiros e comercias ligados ao mundo virtual.

Assinale a alternativa correta.

Coal fire crackdown and London mosque stabbing

(Available in: https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-the-papers-51581385.)

The headline in a British newspaper refers to:

1. It stands for both up-to-date and conventional patterns.

2. People wear it in different ways.

3. Both men and women can wear it.

4. People cannot avoid an arrogant attitude when they put it on.

Mark the affirmative(s) that is/are present in the text.