Questões de Concurso

Para técnico de gestão - administração

Foram encontradas 218 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

Conforme as Disposições Gerais do Estatuto dos Servidores, são proibições do servidor público:

READ THE FOLLOWING TEXT AND CHOOSE THE OPTION WHICH BEST COMPLETES EACH QUESTION ACCORDING TO IT:

Technology has created more jobs than it has destroyed

The battle between men and machines goes back centuries. Are they taking

our jobs? Or are they easing our workload? A study by economists at the consultancy

Deloitte seeks to shed new light on the relationship between jobs and the

rise of technology by searching through census data for England and Wales going

back to 1871.

Their conclusion is that, rather than destroying jobs, technology has been a “great job-creating machine”. Findings by Deloitte such as rise in bar staff since the 1950s or a surge in the number of hairdressers this century suggest to the authors that technology has increased spending power, therefore creating new demand and new jobs. Their study argues that the debate has been twisted towards the job-destroying effects of technological change, which are more easily observed than its creative aspects.

Going back over past figures paints a more balanced picture, say authors Ian Stewart and Alex Cole. “The dominant trend is of contracting employment in agriculture and manufacturing being more than balanced by rapid growth in the caring, creative, technology and business services sectors,” they write. “Machines will take on more repetitive and laborious tasks, but they seem no closer to eliminating the need for human labor than at any time in the last 150 years.”

According to the study, hard, dangerous and dull jobs have declined. In some sectors, technology has quite clearly cost jobs, but they question whether they are really jobs we would want to hold on to. Technology directly substitutes human muscle power and, in so doing, raises productivity and shrinks employment. “In the UK the first sector to feel this effect on any scale was agriculture,” says the study.

The study also found out that ‘caring’ jobs have increased. The report cites a “profound shift”, with labor switching from its historic role, as a source of raw power, to the care, education and provision of services to others. Technological progress has cut the prices of essentials, such as food, and the price of bigger household items such as TVs and kitchen appliances, notes Stewart. That leaves more money to spend on leisure, and creates new demand and new jobs, which may explain the big rise in bar staff, he adds. “_______ the decline in the traditional pub, census data shows that the number of people employed in bars rose fourfold between 1951 and 2011,” the report says.

The Deloitte economists believe that rising incomes have allowed consumers to spend more on personal services, such as grooming. That in turn has driven employment of hairdressers. So, while in 1871 there was one hairdresser or barber for every 1,793 citizens of England and Wales; today there is one for every 287 people.

(Adapted from: https://goo.gl/7V5vuw. Access: 02/02/2018.)

READ THE FOLLOWING TEXT AND CHOOSE THE OPTION WHICH BEST COMPLETES EACH QUESTION ACCORDING TO IT:

Technology has created more jobs than it has destroyed

The battle between men and machines goes back centuries. Are they taking

our jobs? Or are they easing our workload? A study by economists at the consultancy

Deloitte seeks to shed new light on the relationship between jobs and the

rise of technology by searching through census data for England and Wales going

back to 1871.

Their conclusion is that, rather than destroying jobs, technology has been a “great job-creating machine”. Findings by Deloitte such as rise in bar staff since the 1950s or a surge in the number of hairdressers this century suggest to the authors that technology has increased spending power, therefore creating new demand and new jobs. Their study argues that the debate has been twisted towards the job-destroying effects of technological change, which are more easily observed than its creative aspects.

Going back over past figures paints a more balanced picture, say authors Ian Stewart and Alex Cole. “The dominant trend is of contracting employment in agriculture and manufacturing being more than balanced by rapid growth in the caring, creative, technology and business services sectors,” they write. “Machines will take on more repetitive and laborious tasks, but they seem no closer to eliminating the need for human labor than at any time in the last 150 years.”

According to the study, hard, dangerous and dull jobs have declined. In some sectors, technology has quite clearly cost jobs, but they question whether they are really jobs we would want to hold on to. Technology directly substitutes human muscle power and, in so doing, raises productivity and shrinks employment. “In the UK the first sector to feel this effect on any scale was agriculture,” says the study.

The study also found out that ‘caring’ jobs have increased. The report cites a “profound shift”, with labor switching from its historic role, as a source of raw power, to the care, education and provision of services to others. Technological progress has cut the prices of essentials, such as food, and the price of bigger household items such as TVs and kitchen appliances, notes Stewart. That leaves more money to spend on leisure, and creates new demand and new jobs, which may explain the big rise in bar staff, he adds. “_______ the decline in the traditional pub, census data shows that the number of people employed in bars rose fourfold between 1951 and 2011,” the report says.

The Deloitte economists believe that rising incomes have allowed consumers to spend more on personal services, such as grooming. That in turn has driven employment of hairdressers. So, while in 1871 there was one hairdresser or barber for every 1,793 citizens of England and Wales; today there is one for every 287 people.

(Adapted from: https://goo.gl/7V5vuw. Access: 02/02/2018.)

READ THE FOLLOWING TEXT AND CHOOSE THE OPTION WHICH BEST COMPLETES EACH QUESTION ACCORDING TO IT:

Technology has created more jobs than it has destroyed

The battle between men and machines goes back centuries. Are they taking

our jobs? Or are they easing our workload? A study by economists at the consultancy

Deloitte seeks to shed new light on the relationship between jobs and the

rise of technology by searching through census data for England and Wales going

back to 1871.

Their conclusion is that, rather than destroying jobs, technology has been a “great job-creating machine”. Findings by Deloitte such as rise in bar staff since the 1950s or a surge in the number of hairdressers this century suggest to the authors that technology has increased spending power, therefore creating new demand and new jobs. Their study argues that the debate has been twisted towards the job-destroying effects of technological change, which are more easily observed than its creative aspects.

Going back over past figures paints a more balanced picture, say authors Ian Stewart and Alex Cole. “The dominant trend is of contracting employment in agriculture and manufacturing being more than balanced by rapid growth in the caring, creative, technology and business services sectors,” they write. “Machines will take on more repetitive and laborious tasks, but they seem no closer to eliminating the need for human labor than at any time in the last 150 years.”

According to the study, hard, dangerous and dull jobs have declined. In some sectors, technology has quite clearly cost jobs, but they question whether they are really jobs we would want to hold on to. Technology directly substitutes human muscle power and, in so doing, raises productivity and shrinks employment. “In the UK the first sector to feel this effect on any scale was agriculture,” says the study.

The study also found out that ‘caring’ jobs have increased. The report cites a “profound shift”, with labor switching from its historic role, as a source of raw power, to the care, education and provision of services to others. Technological progress has cut the prices of essentials, such as food, and the price of bigger household items such as TVs and kitchen appliances, notes Stewart. That leaves more money to spend on leisure, and creates new demand and new jobs, which may explain the big rise in bar staff, he adds. “_______ the decline in the traditional pub, census data shows that the number of people employed in bars rose fourfold between 1951 and 2011,” the report says.

The Deloitte economists believe that rising incomes have allowed consumers to spend more on personal services, such as grooming. That in turn has driven employment of hairdressers. So, while in 1871 there was one hairdresser or barber for every 1,793 citizens of England and Wales; today there is one for every 287 people.

(Adapted from: https://goo.gl/7V5vuw. Access: 02/02/2018.)

READ THE FOLLOWING TEXT AND CHOOSE THE OPTION WHICH BEST COMPLETES EACH QUESTION ACCORDING TO IT:

Technology has created more jobs than it has destroyed

The battle between men and machines goes back centuries. Are they taking

our jobs? Or are they easing our workload? A study by economists at the consultancy

Deloitte seeks to shed new light on the relationship between jobs and the

rise of technology by searching through census data for England and Wales going

back to 1871.

Their conclusion is that, rather than destroying jobs, technology has been a “great job-creating machine”. Findings by Deloitte such as rise in bar staff since the 1950s or a surge in the number of hairdressers this century suggest to the authors that technology has increased spending power, therefore creating new demand and new jobs. Their study argues that the debate has been twisted towards the job-destroying effects of technological change, which are more easily observed than its creative aspects.

Going back over past figures paints a more balanced picture, say authors Ian Stewart and Alex Cole. “The dominant trend is of contracting employment in agriculture and manufacturing being more than balanced by rapid growth in the caring, creative, technology and business services sectors,” they write. “Machines will take on more repetitive and laborious tasks, but they seem no closer to eliminating the need for human labor than at any time in the last 150 years.”

According to the study, hard, dangerous and dull jobs have declined. In some sectors, technology has quite clearly cost jobs, but they question whether they are really jobs we would want to hold on to. Technology directly substitutes human muscle power and, in so doing, raises productivity and shrinks employment. “In the UK the first sector to feel this effect on any scale was agriculture,” says the study.

The study also found out that ‘caring’ jobs have increased. The report cites a “profound shift”, with labor switching from its historic role, as a source of raw power, to the care, education and provision of services to others. Technological progress has cut the prices of essentials, such as food, and the price of bigger household items such as TVs and kitchen appliances, notes Stewart. That leaves more money to spend on leisure, and creates new demand and new jobs, which may explain the big rise in bar staff, he adds. “_______ the decline in the traditional pub, census data shows that the number of people employed in bars rose fourfold between 1951 and 2011,” the report says.

The Deloitte economists believe that rising incomes have allowed consumers to spend more on personal services, such as grooming. That in turn has driven employment of hairdressers. So, while in 1871 there was one hairdresser or barber for every 1,793 citizens of England and Wales; today there is one for every 287 people.

(Adapted from: https://goo.gl/7V5vuw. Access: 02/02/2018.)

READ THE FOLLOWING TEXT AND CHOOSE THE OPTION WHICH BEST COMPLETES EACH QUESTION ACCORDING TO IT:

Technology has created more jobs than it has destroyed

The battle between men and machines goes back centuries. Are they taking

our jobs? Or are they easing our workload? A study by economists at the consultancy

Deloitte seeks to shed new light on the relationship between jobs and the

rise of technology by searching through census data for England and Wales going

back to 1871.

Their conclusion is that, rather than destroying jobs, technology has been a “great job-creating machine”. Findings by Deloitte such as rise in bar staff since the 1950s or a surge in the number of hairdressers this century suggest to the authors that technology has increased spending power, therefore creating new demand and new jobs. Their study argues that the debate has been twisted towards the job-destroying effects of technological change, which are more easily observed than its creative aspects.

Going back over past figures paints a more balanced picture, say authors Ian Stewart and Alex Cole. “The dominant trend is of contracting employment in agriculture and manufacturing being more than balanced by rapid growth in the caring, creative, technology and business services sectors,” they write. “Machines will take on more repetitive and laborious tasks, but they seem no closer to eliminating the need for human labor than at any time in the last 150 years.”

According to the study, hard, dangerous and dull jobs have declined. In some sectors, technology has quite clearly cost jobs, but they question whether they are really jobs we would want to hold on to. Technology directly substitutes human muscle power and, in so doing, raises productivity and shrinks employment. “In the UK the first sector to feel this effect on any scale was agriculture,” says the study.

The study also found out that ‘caring’ jobs have increased. The report cites a “profound shift”, with labor switching from its historic role, as a source of raw power, to the care, education and provision of services to others. Technological progress has cut the prices of essentials, such as food, and the price of bigger household items such as TVs and kitchen appliances, notes Stewart. That leaves more money to spend on leisure, and creates new demand and new jobs, which may explain the big rise in bar staff, he adds. “_______ the decline in the traditional pub, census data shows that the number of people employed in bars rose fourfold between 1951 and 2011,” the report says.

The Deloitte economists believe that rising incomes have allowed consumers to spend more on personal services, such as grooming. That in turn has driven employment of hairdressers. So, while in 1871 there was one hairdresser or barber for every 1,793 citizens of England and Wales; today there is one for every 287 people.

(Adapted from: https://goo.gl/7V5vuw. Access: 02/02/2018.)

READ THE FOLLOWING TEXT AND CHOOSE THE OPTION WHICH BEST COMPLETES EACH QUESTION ACCORDING TO IT:

Technology has created more jobs than it has destroyed

The battle between men and machines goes back centuries. Are they taking

our jobs? Or are they easing our workload? A study by economists at the consultancy

Deloitte seeks to shed new light on the relationship between jobs and the

rise of technology by searching through census data for England and Wales going

back to 1871.

Their conclusion is that, rather than destroying jobs, technology has been a “great job-creating machine”. Findings by Deloitte such as rise in bar staff since the 1950s or a surge in the number of hairdressers this century suggest to the authors that technology has increased spending power, therefore creating new demand and new jobs. Their study argues that the debate has been twisted towards the job-destroying effects of technological change, which are more easily observed than its creative aspects.

Going back over past figures paints a more balanced picture, say authors Ian Stewart and Alex Cole. “The dominant trend is of contracting employment in agriculture and manufacturing being more than balanced by rapid growth in the caring, creative, technology and business services sectors,” they write. “Machines will take on more repetitive and laborious tasks, but they seem no closer to eliminating the need for human labor than at any time in the last 150 years.”

According to the study, hard, dangerous and dull jobs have declined. In some sectors, technology has quite clearly cost jobs, but they question whether they are really jobs we would want to hold on to. Technology directly substitutes human muscle power and, in so doing, raises productivity and shrinks employment. “In the UK the first sector to feel this effect on any scale was agriculture,” says the study.

The study also found out that ‘caring’ jobs have increased. The report cites a “profound shift”, with labor switching from its historic role, as a source of raw power, to the care, education and provision of services to others. Technological progress has cut the prices of essentials, such as food, and the price of bigger household items such as TVs and kitchen appliances, notes Stewart. That leaves more money to spend on leisure, and creates new demand and new jobs, which may explain the big rise in bar staff, he adds. “_______ the decline in the traditional pub, census data shows that the number of people employed in bars rose fourfold between 1951 and 2011,” the report says.

The Deloitte economists believe that rising incomes have allowed consumers to spend more on personal services, such as grooming. That in turn has driven employment of hairdressers. So, while in 1871 there was one hairdresser or barber for every 1,793 citizens of England and Wales; today there is one for every 287 people.

(Adapted from: https://goo.gl/7V5vuw. Access: 02/02/2018.)

READ THE FOLLOWING TEXT AND CHOOSE THE OPTION WHICH BEST COMPLETES EACH QUESTION ACCORDING TO IT:

Technology has created more jobs than it has destroyed

The battle between men and machines goes back centuries. Are they taking

our jobs? Or are they easing our workload? A study by economists at the consultancy

Deloitte seeks to shed new light on the relationship between jobs and the

rise of technology by searching through census data for England and Wales going

back to 1871.

Their conclusion is that, rather than destroying jobs, technology has been a “great job-creating machine”. Findings by Deloitte such as rise in bar staff since the 1950s or a surge in the number of hairdressers this century suggest to the authors that technology has increased spending power, therefore creating new demand and new jobs. Their study argues that the debate has been twisted towards the job-destroying effects of technological change, which are more easily observed than its creative aspects.

Going back over past figures paints a more balanced picture, say authors Ian Stewart and Alex Cole. “The dominant trend is of contracting employment in agriculture and manufacturing being more than balanced by rapid growth in the caring, creative, technology and business services sectors,” they write. “Machines will take on more repetitive and laborious tasks, but they seem no closer to eliminating the need for human labor than at any time in the last 150 years.”

According to the study, hard, dangerous and dull jobs have declined. In some sectors, technology has quite clearly cost jobs, but they question whether they are really jobs we would want to hold on to. Technology directly substitutes human muscle power and, in so doing, raises productivity and shrinks employment. “In the UK the first sector to feel this effect on any scale was agriculture,” says the study.

The study also found out that ‘caring’ jobs have increased. The report cites a “profound shift”, with labor switching from its historic role, as a source of raw power, to the care, education and provision of services to others. Technological progress has cut the prices of essentials, such as food, and the price of bigger household items such as TVs and kitchen appliances, notes Stewart. That leaves more money to spend on leisure, and creates new demand and new jobs, which may explain the big rise in bar staff, he adds. “_______ the decline in the traditional pub, census data shows that the number of people employed in bars rose fourfold between 1951 and 2011,” the report says.

The Deloitte economists believe that rising incomes have allowed consumers to spend more on personal services, such as grooming. That in turn has driven employment of hairdressers. So, while in 1871 there was one hairdresser or barber for every 1,793 citizens of England and Wales; today there is one for every 287 people.

(Adapted from: https://goo.gl/7V5vuw. Access: 02/02/2018.)

READ THE FOLLOWING TEXT AND CHOOSE THE OPTION WHICH BEST COMPLETES EACH QUESTION ACCORDING TO IT:

Technology has created more jobs than it has destroyed

The battle between men and machines goes back centuries. Are they taking

our jobs? Or are they easing our workload? A study by economists at the consultancy

Deloitte seeks to shed new light on the relationship between jobs and the

rise of technology by searching through census data for England and Wales going

back to 1871.

Their conclusion is that, rather than destroying jobs, technology has been a “great job-creating machine”. Findings by Deloitte such as rise in bar staff since the 1950s or a surge in the number of hairdressers this century suggest to the authors that technology has increased spending power, therefore creating new demand and new jobs. Their study argues that the debate has been twisted towards the job-destroying effects of technological change, which are more easily observed than its creative aspects.

Going back over past figures paints a more balanced picture, say authors Ian Stewart and Alex Cole. “The dominant trend is of contracting employment in agriculture and manufacturing being more than balanced by rapid growth in the caring, creative, technology and business services sectors,” they write. “Machines will take on more repetitive and laborious tasks, but they seem no closer to eliminating the need for human labor than at any time in the last 150 years.”

According to the study, hard, dangerous and dull jobs have declined. In some sectors, technology has quite clearly cost jobs, but they question whether they are really jobs we would want to hold on to. Technology directly substitutes human muscle power and, in so doing, raises productivity and shrinks employment. “In the UK the first sector to feel this effect on any scale was agriculture,” says the study.

The study also found out that ‘caring’ jobs have increased. The report cites a “profound shift”, with labor switching from its historic role, as a source of raw power, to the care, education and provision of services to others. Technological progress has cut the prices of essentials, such as food, and the price of bigger household items such as TVs and kitchen appliances, notes Stewart. That leaves more money to spend on leisure, and creates new demand and new jobs, which may explain the big rise in bar staff, he adds. “_______ the decline in the traditional pub, census data shows that the number of people employed in bars rose fourfold between 1951 and 2011,” the report says.

The Deloitte economists believe that rising incomes have allowed consumers to spend more on personal services, such as grooming. That in turn has driven employment of hairdressers. So, while in 1871 there was one hairdresser or barber for every 1,793 citizens of England and Wales; today there is one for every 287 people.

(Adapted from: https://goo.gl/7V5vuw. Access: 02/02/2018.)

Analise os seguintes argumentos:

I. Se estudasse todo o conteúdo, então seria aprovado em Estatística. Fui reprovado em Estatística. Concluímos que não estudei todo o conteúdo.

II. Todo estudante gosta de Geometria. Nenhum atleta é estudante. Concluímos que ninguém que goste de Geometria é atleta.

III.Toda estrela possui luz própria. Nenhum planeta do sistema solar possui luz própria. Concluímos que nenhuma estrela é um planeta.

Considerando os argumentos I, II e III, é CORRETO afirmar que

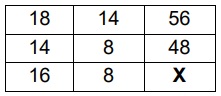

Na tabela a seguir, o número que ocupa a extrema direita em cada uma de suas

linhas é o resultado de operações efetuadas com os outros dois números da

mesma linha. Se a sucessão de operações é a mesma em todas as linhas, então

é CORRETO afirmar que o valor de X é igual a:

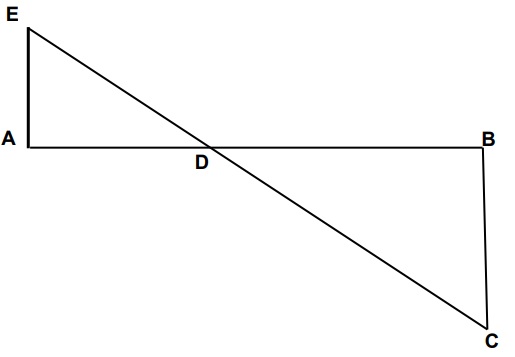

A figura a seguir se constitui de dois triângulos retângulos em A e B, sendo as

medidas dos segmentos AB = 3, AE = 700 e BC = 200 unidades de comprimento.

Nessas condições, é CORRETO afirmar que a medida do segmento DB, em unidades

de comprimento, é igual a:

Texto II

Razões da pós-modernidade

Carlos Alberto Sanches, professor, perito e consultor em Redação – [31/03/2014- 21h06]

Foi nos anos 60 que surgiu o que se chama de “pós-modernidade”, na abalizada opinião de Frederic Jameson, como “uma lógica cultural” do capitalismo tardio, filho bastardo do liberalismo dos séculos 18 e 19. O tema é controverso, pois está associado a uma discussão sobre sua emergência funesta no pós-guerra. É que ocorre nesse período um profundo desencanto no homem contemporâneo, especialmente no que toca à diluição e abalo de seus valores axiológicos, como verdade, razão, legitimidade, universalidade, sujeito e progresso etc. Os sonhos se esvaneceram, juntamente com os valores e alicerces da vida: a “estética”, a “ética” e a “ciência”, e as repercussões que isso provocou na produção cultural: literatura, arte, filosofia, arquitetura, economia, moral etc.

Há, sem dúvida, uma crise cultural que desemboca, talvez, em uma crise de modernidade. Ou a constatação de que, rompida a modernidade, destroçada por guerras devastadoras, produto da “gaia ciência” libertadora, leva a outra ruptura: morreu a pós-modernidade e deixou órfã a cultura contemporânea?

Seria o caso de se falar em posteridade na pós-modernidade? Max Weber, já no início do século 19, menciona a chegada da modernidade trocada pela “racionalização intelectualista”, que produz o “desencanto do mundo”. Habermas o reinterpreta, dizendo que a civilização se desagrega, especialmente no que toca aos conceitos da verdade, da coerência das leis, da autenticidade do belo, ou seja, como questões de conhecimento...

Jean Francois Lyotard, em seu livro A condição pós-moderna, de 1979, enfoca a legitimação do conhecimento na cultura contemporânea. Para ele, “o pós-moderno enquanto condição de cultura, nesta era pós-industrial, é marcado pela incredulidade face ao metadiscurso filosófico – metafísico, com suas pretensões atemporais e universalizantes”. É como se disséssemos, fazendo coro, mais tarde, com John Lennon, que “o sonho acabou” (ego trip). A razão, como ponto nevrálgico da cultura moderna, não leva a nada, a não ser à certeza de que o racionalismo iluminista, que vai entronizar a ciência como uma mola propulsora para a criação de uma sociedade justa, valorizadora do indivíduo, vai apenas produzir o desencanto, via progresso e com as suas descobertas, cantadas em prosa e verso, que nos deixaram um legado brutal: as grandes tragédias do século 20: guerras atrozes, a bomba atômica, crise ecológica, a corrida armamentista...

A frustração é enorme, porque o iluminismo afirmara que somente as luzes da razão poderiam colocar o homem como gerador de sua história. Mas tudo não passou de um sonho, um sonho de verão (parodiando Shakespeare). Habermas coloca nessa época, o século 18, o gatilho que vai acionar essa desilusão da pós-modernidade. A ciência prometia dar segurança ao homem e lhe deu mais desgraças. Entendamos aqui também a racionalidade (o primado da razão cartesiana) como cúmplice dessa falcatrua da modernidade e, portanto, da atual pós-modernidade.

O mesmo filósofo fala em “desastre da modernidade”, um tipo de doença que produziu uma patologia social chamada de “império da ciência”, despótico e tirânico, que “digere” as esferas estético-expressivas e as religiosas-morais. Harvey põe o dedo na ferida ao dizer que o projeto do Iluminismo já era, na origem, uma “patranha”, na medida em que disparava um discurso redentor para o homem com as luzes da razão, em troca da lenta e gradual perda de sua liberdade.

A partir dos anos 50 e, ocorrido agora o definitivo desencanto com a ciência e suas tragédias (algumas delas), pode-se falar em um processo de sua desaceleração. O nosso futuro virou uma incerteza. A razão, além de não nos responder às grandes questões que prometeu responder, engendra novas e terríveis perguntas, que chegam até hoje, vagando sobre a incerteza de nossos precários destinos. Eu falaria, metaforicamente, do homem moderno acorrentado (o Prometeu) ao consumo desenfreado de coisas (res) para compensar suas frustrações e angústias. A vida se tornou absurda e difícil de ser vivida, face a esse “mal-estar” do homem ocidental. Daí surgem as grandes doenças psicossociais de hoje: a frustração, o relativismo e o niilismo, cujas sementes já estavam no bojo do Iluminismo, a face sinistra de sua moeda. Não há mais nenhuma certeza, porque a razão não foi capaz de dar ao homem alguns dos mais gratos dos bens: sua segurança e bem-estar. Não há mais certezas, apenas a percepção de que é preciso repensar criticamente a ciência, que nunca nos ofereceu um caminho para a felicidade, o que provoca um forte movimento de busca de liberdade. O mundo está sem ordem e valores, como disse Dostoievski: “Se Deus não existe, tudo é permitido”.

A incerteza do mundo moderno e a impossibilidade de organizar nossas vidas levam Giddens a dizer que “não há nada de misterioso no surgimento dos fundamentalismos, a radicalização para as angústias do homem”. Restou-nos o refúgio nos grandes espetáculos, como os do Coliseu antigo: o pão e o circo, para preencher o vazio da vida.

Na sua esteira de satanização social, o capitalismo engendra, então, a sociedade de consumo, para levar o cidadão ao ópio do consumo (esquecer-se das desilusões) nas “estações orbitais” dos shoppings, ou templos das compras, onde os bens nos consomem e a produção, sempre crescente, implica a criação em massa (ou em série) de novos consumidores. Temos uma parafernália de bens, mas são em sua maioria coisas inúteis, que a razão / ciência nos deu; mas, em troca, sofremos dos males do século, entre eles a elisão de nossa individualidade. Foi uma troca desvantajosa. É o que Campbell chama do sonho que gera o “signo-mercadoria”, que nos remete ao antigo sonho do Romantismo, da realização dos ideais.

Trocamos o orgasmo reprodutor instintivo pelo prazer lúdico-frenético de consumir, sem saber que somos consumidos. Gememos de prazer ao comprar, mas choramos de dor face à nossa solidão, cercados pela panaceia da ciência e da razão, que nos entope de placebos, mas não de remédios para a cura dos males dessa longínqua luz racional, que se acende lá no Iluminismo e que vem, sob outras formas, até hoje. A televisão nos anestesia com a estética da imagem. Para Baudrillard, ela é o nosso mundo, como o mundo saído da tela do grande filme O Vidiota (o alienado no mundo virtual da tevê), cujo magistral intérprete foi Peter Sellers.

Enquanto nos deleitamos com essa vida esquizofrênica e lúdica, deixamos no caixa do capitalismo tardio (iluminista / racional) o nosso mais precioso bem: a individualidade. Só nos sobrou a estética, segundo Jameson, ou a “colonização pela estética” que afeta diferentes aspectos da cultura, como a estética, a ética, a teórica, além da moral política.

A pós-modernidade talvez seja uma reação a esse quadro desolador. Bauman

fala em pós-modernidade como a forma atual da modernidade longínqua. Já

Giddens fala em modernidade tardia ou “modernidade radicalizada”: a cultura

atual. Por certo que a atual discussão sobre o pós-moderno implica um processo

de revisão e questionamento desse estado de coisas, em que o homem não passa

de um res nulius, como as matronas romanas.

A cultura moderna, ou pós-modernista, não tem uma razão para produzir

sua autocrítica, mas muitas razões, devido à sua prolongada irracionalidade do

“modo de vida global”, segundo Jameson. O que se pode dizer é que não há uma

razão, mas muitas razões para reordenar criticamente os descaminhos da pós-modernidade,

sem esquecermos que a irracionalidade continua nos rondando.

http://www.gazetadopovo.com.br/opiniao/artigos/razoes-da-pos-modernidade8bs4bc7sv5e06z8trfk0pv80e.

Acesso em 21/01/18.

Atente para a semântica introduzida pelos conectivos (palavras ou locuções) destacados

e assinale a afirmação INCORRETA: