Questões de Concurso Público AGU 2014 para Analista de Sistemas

Foram encontradas 80 questões

( ) À Procuradoria-Geral Federal compete a apuração da liquidez e certeza dos créditos, de qualquer natureza, inerentes às atividades das autarquias e fundações públicas federais, inscrevendo-os em dívida ativa, para fins de cobrança amigável ou judicial.

( ) Para cada Procuradoria de autarquia ou fundação federal de âmbito nacional e para as Procuradorias Federais não especializadas haverá setor comum de cálculos e perícias.

( ) A Procuradoria-Geral Federal é órgão vinculado à Advocacia-Geral, sendo por ela supervisionada, estando também a ela subordinada no que diz respeito à autonomia administrativa e financeira.

A sequência está correta em

II. A recusa de fé a documentos públicos é considerada falta gravíssima, devendo contra o servidor que assim agiu ser aplicada a penalidade de demissão.

III. A acumulação ilegal de cargos públicos é penalizável com demissão, sendo que a lei prevê a possibilidade de o servidor apresentar opção no prazo improrrogável de dez dias, contados da data da ciência, após ser notificado conforme procedimento previsto em lei.

IV. Entende-se por inassiduidade habitual a falta ao serviço, sem causa justificada, por trinta dias, interpoladamente, durante o período de doze meses.

Estão INCORRETAS apenas as afirmativas

I. Quando se tratar de Membros das Carreiras da Advocacia-Geral da União submetidos à estágio confirmatório, caberá à Corregedoria-Geral da Advocacia da União decidir sobre a confirmação no cargo ou exoneração.

II. A emissão de parecer sobre o desempenho dos integrantes das Carreiras da Advocacia-Geral da União submetidos ao estágio confirmatório, opinando, fundamentadamente, por sua confirmação no cargo ou exoneração, cabe ao Conselho Superior da Advocacia-Geral da União.

III. Incumbe ao Advogado-Geral da União homologar os concursos públicos de ingresso nas Carreiras da Advocacia-Geral da União.

IV. A Consultoria-Geral da União coordenará o estágio confirmatório dos integrantes das Carreiras da Advocacia-Geral da União.

Está(ão) correta(s) apenas a(s) afirmativa(s)

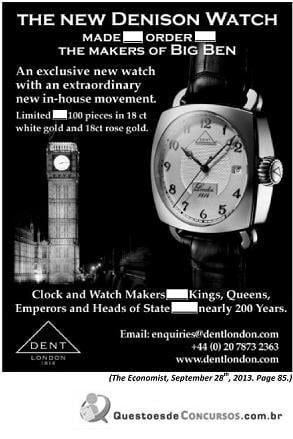

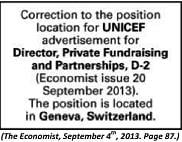

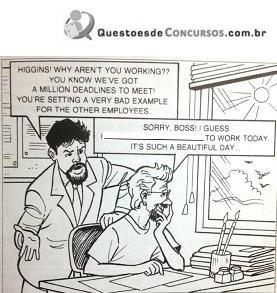

Choose the sequence to fill in the blanks

The ad contains a/an

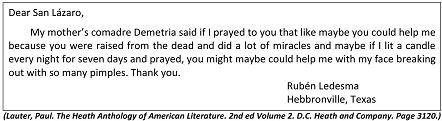

It is true about the message that

(Disponívelem: http://www.estadao.com.br/noticias/nacional,justica-acata-denuncia-contra-acusados-pelo-atentado-do-riocentro,1167081,0.htm, em 15 de maio de 2014, às 12606.)

(Disponívelem: http://www.estadao.com.br/noticias/nacional,justica-acata-denuncia-contra-acusados-pelo-atentado-do-riocentro,1167081,0.htm, em 15 de maio de 2014, às 12606.)

(Disponivel em: 01-www.g1.globo.com-em12/o1/2014, as17h40.)

(Disponivel em: 01-www.g1.globo.com-em12/o1/2014, as17h40.)

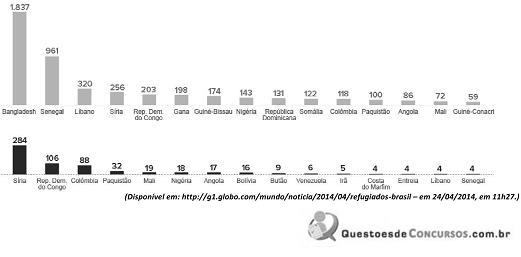

Analisando os gráficos, é correto afirmar que

I. liderando a relação de pai'ses com maior número de concessões em 2013 está a nação que vive um dos mais sanguiná- rios conflitos do planeta.

II. metade dos pedidos e concessões de refúgio registrados em 2013 veio da região asiática do Oriente Médio.

III. os países que lideram a lista de pedidos e concessões são do continente asiático.

IV. os pedidos de refúgio são todos oriundos da África e Ásia.

As afirmativas corretas referentes aos dados apresentados nos gráficos são apenas