Questões de Concurso

Foram encontradas 4.572 questões

Resolva questões gratuitamente!

Junte-se a mais de 4 milhões de concurseiros!

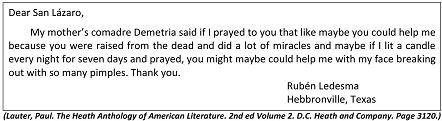

It is true about the message that

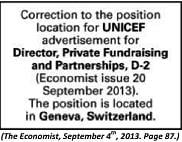

The ad contains a/an

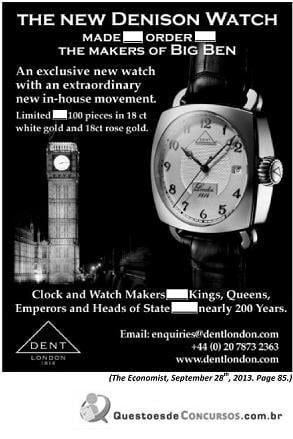

Choose the sequence to fill in the blanks

II. A recusa de fé a documentos públicos é considerada falta gravíssima, devendo contra o servidor que assim agiu ser aplicada a penalidade de demissão.

III. A acumulação ilegal de cargos públicos é penalizável com demissão, sendo que a lei prevê a possibilidade de o servidor apresentar opção no prazo improrrogável de dez dias, contados da data da ciência, após ser notificado conforme procedimento previsto em lei.

IV. Entende-se por inassiduidade habitual a falta ao serviço, sem causa justificada, por trinta dias, interpoladamente, durante o período de doze meses.

Estão INCORRETAS apenas as afirmativas

Diante de tal situação, acerca da responsabilização civil decorrente de tal ato, assinale a afirmativa correta.

I. Os vencimentos dos cargos do Poder Legislativo e do Poder Judiciário não poderão ser superiores aos pagos pelo Poder Executivo.

II. A remuneração e o subsídio dos ocupantes de cargos, funções e empregos públicos da administração direta, autárquica e fundacional, dos membros de qualquer dos Poderes da União, dos Estados, do Distrito Federal e dos Municípios, dos detentores de mandato eletivo e dos demais agentes políticos e os proventos, pensões ou outra espécie remuneratória, percebidos cumulativamente ou não, incluídas as vantagens pessoais ou de qualquer outra natureza, não poderão exceder o subsídio mensal, em espécie, dos Ministros do Supremo Tribunal Federal.

III. É vedada a vinculação ou equiparação de quaisquer espécies remuneratórias para o efeito de remuneração de pessoal do serviço público.

Está(ão) correta(s) a(s) afirmativa(s)

“Este não é um serviço de imprensa secreto. Todo nosso trabalho é feito às claras. Pretendemos fazer a divulgação de notícias. Isto não é agenciamento de anúncios. Se acharem que o nosso assunto ficaria melhor na seção comercial, não usem. Nosso assunto é exato. Maiores detalhes, sobre qualquer questão, serão dados prontamente. E qualquer diretor de jornal interessado será auxiliado, com o maior prazer, na verificação direta de qualquer declaração de fato. Em resumo, nosso plano é divulgar, prontamente, para o bem das empresas e das instituições públicas, com absoluta franqueza, à imprensa e ao público dos Estados Unidos, informações relativas a assuntos de valor e de interesse para o público.”

É correto afirmar que o texto é um(a) .

1. Atos de Improbidade Administrativa que Importam Enriquecimento Ilícito.

2. Atos de Improbidade Administrativa que Causam Prejuízo ao Erário.

3. Atos de Improbidade Administrativa que Atentam Contra os Princípios da Administração Pública.

( ) Permitir, facilitar ou concorrer para que terceiro se enriqueça ilicitamente.

( ) Perceber vantagem econômica para intermediar a liberação ou aplicação de verba pública de qualquer natureza.

( ) Frustrar a licitude de processo licitatório ou dispensá-lo indevidamente.

( ) Frustrar a licitude de concurso público.

Assinale a sequência de códigos que corresponde corretamente às categorias em que se enquadram as condutas, na ordem em que são apresentadas e conforme a legislação mencionada.

( ) Toda ausência injustificada do servidor de seu local de trabalho é fator de desmoralização do serviço público, o que quase sempre conduz à desordem nas relações humanas.

( ) A omissão de publicidade de ato administrativo constitui comprometimento ético contra o bem comum, podendo esta ser admitida, contudo, exclusivamente quando ocorrer caso de interesse superior do Estado e da Administração Pública.

( ) A função pública deve ser tida como exercício profissional e, portanto, se integra na vida particular de cada servidor público. Todavia, a intimidade do servidor é inviolável, de forma que os fatos e atos verificados na conduta do dia a dia em sua vida privada não poderão acrescer ou diminuir o seu bom conceito na vida funcional.

( ) O atraso na prestação do serviço não caracteriza apenas atitude contra a ética ou ato de desumanidade, mas, principalmente, grave dano moral aos usuários dos serviços públicos.

A sequência está correta em

I. "A resposta a uma questão de referência deve incluir os elementos que serviram para sua elaboração: a própria questão, a estratégia da pesquisa, os instrumentos bibliográficos utilizados e os resultados na forma de referências dos documentos ou dos próprios documentos ou cópias contendo, obrigatoriamente, a identificação das fontes."

PORQUE

II. "A entrevista de referência é um processo impessoal pois implica no atendimento ao público mais amplo possível, oferecendo acervos de todos os tipos, sobre todos os assuntos."

Assinale a alternativa correta.